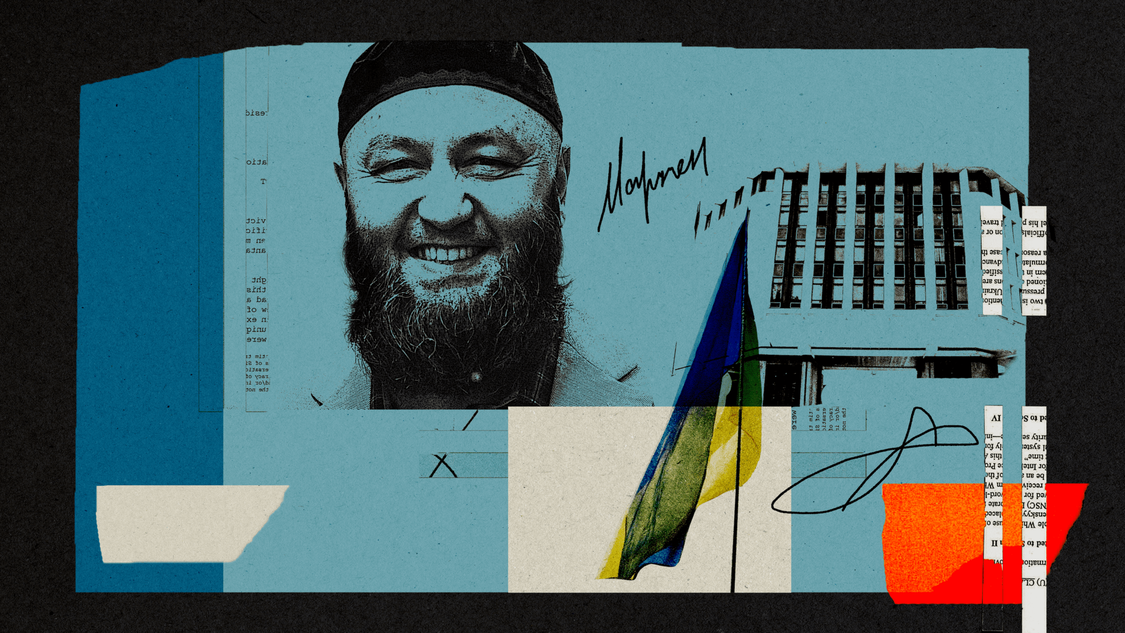

Server Mustafayev is a Ukrainian human rights advocate and citizen journalist. He was born on May 5, 1986, in the township of Ziadin in the Samarkand region of Uzbekistan. His family later resettled in Crimea, their homeland.

He graduated with honors from Bakhchysarai Construction College, specializing in the operation of gas supply equipment and systems. He worked for Evromerezha, a communications company, and later in the sales department at Astelit. From 2006 to 2012, he studied at Kyiv National University, where he earned a master’s degree in heat and gas supply, as well as ventilation.

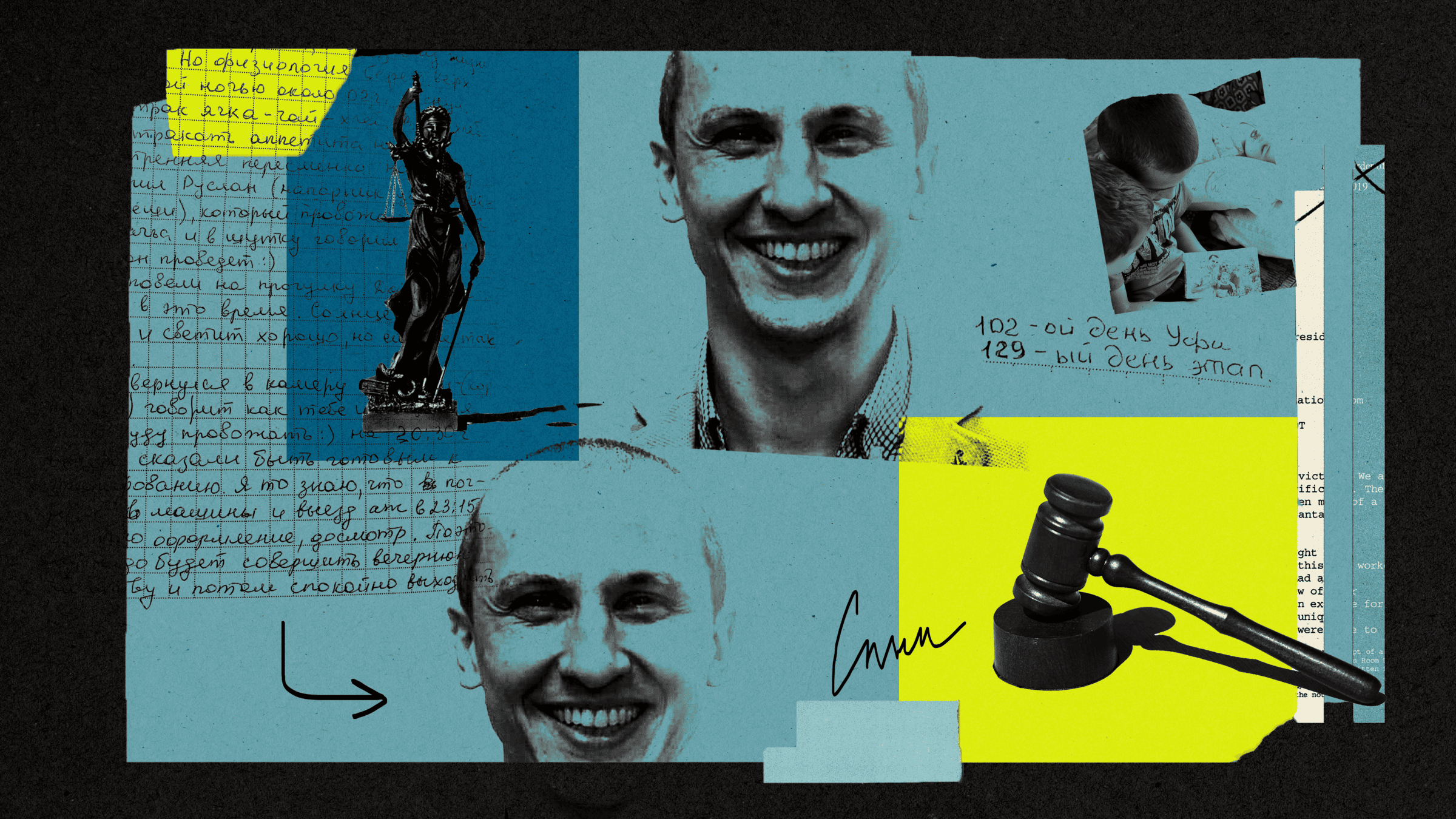

On May 21, 2018, the FSB officers detained and arrested Mustafayev after searching his home in Bakhchysarai. He was charged under two articles of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation: Part 2 of Article 205.5 (“Participation in the activities of a terrorist organization”) and Part 1 of Article 30 and Article 278 (“Preparing for actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power or the forcible retention of power”). Two years later, on September 16, 2020, he was sentenced to fourteen years in a strict-regime penal colony. He is currently serving his sentence in the Penal Colony No. 1 in the Tambov region of Russia.

A number of Ukrainian and international human rights organizations insist that the charges against Mustafayev and all members of the Bakhchysarai Hizb ut-Tahrir group are politically motivated.

Mustafayev has been awarded the honorary state award of Ukraine, the Third Class Order of Merit.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

Arrest during Ramadan

The month of Ramadan is the time when all Muslims are required to fast. It is considered a holy month by everyone who practices Islam. The night of May 21, 2018, was the sixth night of Ramadan that year. Server Mustafayev woke up for morning prayer in his house in Bakhchysarai. I, the author of this essay, was on a business trip in Crimea, finishing another report on persecution and oppression in the peninsula. Without checking the time, I texted Mustafayev (later confirming it was around four in the morning) to arrange a meeting to get his commentary to include in the report I was working on.

He responded surprisingly quickly. After a brief exchange, he told me I should get some sleep. I went to bed in the early hours, turning off my laptop and setting my phone to silent mode. When I woke up in the early afternoon, I learned that the FSB officers had detained Mustafayev in his home around six in the morning—just two hours after our conversation, which turned out to be the last one we had while he was still free. Later, I would write him letters of support, first to the pre-trial detention center in Simferopol and then to the penal colony in Russia.

Sharing everyone’s pain

Before Crimea was occupied, Mustafayev was a Ukrainian human rights advocate. One of the most high-profile cases in which Mustafayev was involved in Crimea is known as “the case of the headscarf.” In January 2010, Susanna Ismailova, a Crimean Tatar and Muslim, filed a lawsuit against the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs after the passport office in Bakhchysarai did not allow her to have her passport photo taken while wearing her hijab. Ismailova explained her position: “I’ve been wearing a hijab, as the Qur’an commands, for a decade. I’d feel uncomfortable going outside without it. People probably wouldn’t even recognize me. It’s like someone wearing glasses their whole life suddenly takes them off. At the same time, people wearing glasses don’t have to remove them when having their passport photo taken.”

Many Muslim women in Crimea supported Ismailova, advocating for their right to have document photos taken in accordance with their religious traditions. Mustafayev and his colleagues provided Ismailova with legal advice on this issue. Lawyer Lilia Gemedzhi says, “This coalition was called the ‘Human Rights Movement of Crimea,’ and it was headed by Edem Semedliaev [today, one of the independent attorneys in Crimea defending Crimean political prisoners]. Representatives of this movement were active in almost all regions of the peninsula. In the Bakhchysarai region, this was Mustafayev. All of them carried yellow and blue ID cards.” She adds that Mustafayev and his team of human rights advocates tracked instances of incitement to hatred on ethnic and religious grounds.

Back then, Gemedzhi did not know Mustafayev personally. They met in 2016. One day, Gemedzhi and her colleagues went to a downstairs café for lunch, and Mustafayev joined them. Gemedzhi recalls: “The subject of cell phones came up. How do you set up this feature that keeps your phone off in case of detainment or attack yet sends distress messages to chosen contacts and lets them hear what is happening in your surroundings?”

Later, Gemedzhi and Mustafayev met many times after house searches and trials. Once, a trial took too long, and the attorneys did not have enough time to pray Salah [a Muslim prayer performed at a specific time], so Mustafayev invited all of them over to his home to pray. His wife, Maye, treated them to a meal. Since then, Gemedzhi and Mustafayev, along with their families, have been close friends. Mustafayev became one of Gemedzhi’s first clients after she was licensed to practice law. “By the way, it was Server who insisted that I should get a license,” she says.

Lutfiye Zudiyeva, a journalist and human rights advocate, says that Mustafayev was one of the founders of the Crimean Solidarity. In 2017, after a trial against Zarema Umerova, who was fined 300 thousand rubles [around 127 thousand hryvnias, or $3,300] by the court in Crimea for her pro-Ukrainian posts on social media, Mustafayev and other activists launched a campaign called “Unity Costs More than Fines.”

Zudiyeva explains: “By that time, security officials had already realized that detaining activists for administrative offenses for a few days was ineffective. People jumped back into action as soon as they were released. So, they started imposing fines. Mustafayev came up with the idea for a campaign urging people to donate 10 rubles [around 4 hryvnias, or ten American cents] to pay the fines. This small amount wouldn’t hit your wallet, while activists and citizen journalists charged with administrative offenses would know that if they were arrested, the fines wouldn’t become a burden for them or their families. People would help them out.”

The initiative snowballed unexpectedly, spreading far beyond Crimea. Donations poured in from Turkey, Romania, and even Canada. At some point, the Crimean Solidarity even had to post an announcement pausing their fundraising campaign, asking people not to donate any further.

Umerova’s fine equaled 140 kilograms of coins, which activists lugged to the local bank office in bags, buckets, and plastic bags.

“I feel like Scrooge McDuck,” the bank employee joked when accepting the payment. “I wish our people shared everyone’s pain,” Mustafayev remarked back then.

“We’ll be next.”

In April 2018, Mustafayev and his fellow citizens traveled to Turkey. They met with Andrii Sybiha, the then Ambassador of Ukraine to the Republic of Turkey. When the ambassador asked if they were afraid to return to Crimea and continue their activism, Mustafayev replied: “We’ll be next,” meaning that all activists in Crimea knew they could also be arrested at any time. But they kept working toward their cause. Later, in a letter from prison, Mustafayev would write: “My entire ‘fault,’ just like that of any political prisoner and those persecuted on the outside […] is my steadfast civic and social activism, especially since 2014, the courage to publicly speak the truth and hold my own opinions on the systemic injustices and persecutions based on nationality, ethnicity, and religion, which have been ‘legitimized’ in the Russian Federation for over a decade and in Crimea since 2014.”

On his way back from Turkey, Mustafayev was detained at the administrative entry point to Crimea. He calmed his wife, Maye, who was very anxious about him, by saying: “I bought a bunch of really nice jackets in Turkey, so border guards are now asking me where I found them.” Later, after his arrest, Mustafayev would ask his wife to bring one of the jackets he bought in Turkey to the court hearing. “Server firmly believed that even behind bars, one should never stoop to the level of a typical prisoner,” Lilia Gemedzhi says.

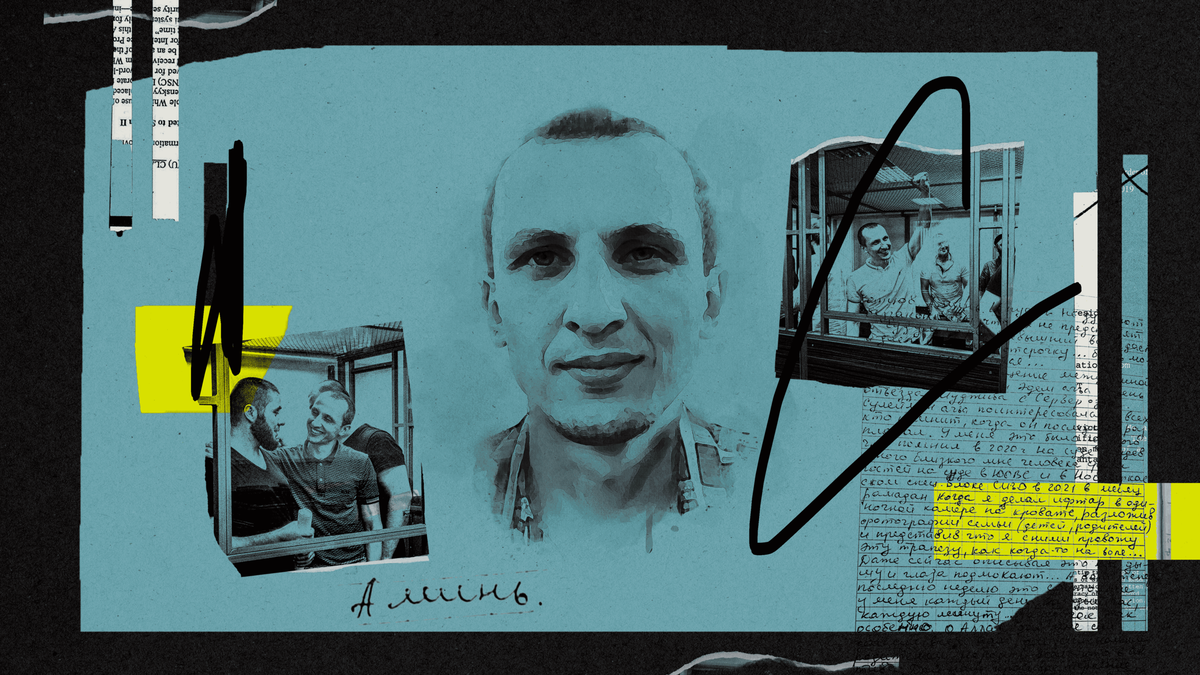

On the morning of May 21, 2018, Mustafayev’s house was searched. This is a fragment of one of the first interviews I recorded with Mustafayev’s wife, Maye: “I was stirred awake by the noise. They [Russian security officers] were already in the hallway. I woke my parents up, and we got dressed. My father opened the door. They didn’t barge into our home. They simply walked in. Server read the court ruling. They started searching the house: first the kitchen, then the bedroom, and then the rest of the rooms, one by one. They looked into every gap. They confiscated our cell phones and laptop, but they didn’t record taking the children’s tablet. Essentially, they just stole it. During the search, they knocked my father to the floor and twisted his arm. He spent two weeks with his arm in a cast afterward, nursing a bad bruise and a head injury. When I heard the commotion that morning, I immediately thought, “Ramadan is the most blessed month for us. How did they even dare to come here during the fast?” I spoke with Maye many times after that. I recorded our conversation for this essay right after her extended visit to her husband in the Russian colony.

“He was curious about everything.”

If you type the names of two cities—Bakhchysarai and Tambov—into Google Maps, you’ll see that the distance between them totals 1,263 kilometers. It is the shortest route according to the map. Today, Mustafayev is held in Colony No. 1 in the Russian city of Tambov. It took his family more than 26 hours to travel there. Maye was surprised to find the colony right in the city center rather than on the outskirts or beyond.

Mustafayev’s parents and his two children also made the journey to see him. His father, Rustem Mustafayev, hugged his son for the first time in the six years since his arrest. An extended visit lasts two nights and three days. “You see your husband next to you, and you can’t believe that you can touch him just like that. And knowing that in three days, they will take him away from you again is the hardest,” Maye says, describing the emotions she carries with her after visiting her husband.

Mustafayev is now held in a high-security cell. This is how he briefly describes his daily routine: Lights on at 6 a.m., lights out at 10 p.m. Sleeping a few minutes longer is considered a violation and can result in being sent to a punitive isolation cell. During winter and early spring, prisoners are rarely taken outside: They may not even spend an hour outdoors due to the cold climate and are prohibited from returning indoors sooner. In prison, Mustafayev learned how to sew. His first pieces were for children: onesies and undershirts. He sent a few samples of his work to his family. “I was shocked,” says Maye. “Perfect stitches and hems, such a careful handiwork. I don’t even know how to sew, while Server learned that in the colony of all places.” She adds that her husband also exercises, borrows books from the library, and regularly asks her to send him new books. Among those she sent were World Order by Henry Kissinger, Papillon by Henri Charrière, and The Mauritanian by Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

In the colony, Mustafayev only has access to Russian news. Maye says that despite this, her husband is well-informed about current events: “He watches the Russian news and simply interprets whatever they say on TV to mean the opposite. This way, he understands what’s actually happening.” In one of his letters from prison, Mustafayev wrote: “I always try to keep track of all Crimean, Ukrainian, and world news to the best of my ability, despite confinement, prohibitions, and the torturous conditions in contemporary Russian Gulags.”

Any news is important for all political prisoners since our freedom and imprisonment are directly related to the politics of the Russian Federation that occupied Crimea—and to the policies of other countries.

During the most recent visit, Mustafayev asked Maye and his father about everything happening in his hometown of Bakhchysarai. He inquired about his family and friends, sending his greetings and personal words of gratitude for their support. “He was curious about everything,” Maye recalls. “And the most wonderful thing is that he hasn’t lost his optimism after six years in prison. Mustafayev believes he won’t have to do his entire term. More and more often, he says that the smell of freedom is close.”

Even during his time in pre-trial detention or now in a high-security prison, Mustafayev continues his human rights advocacy. He assists in writing complaints and recently helped a citizen of Uzbekistan, who does not speak Russian, prepare necessary documents for his court case. They could understand each other through Crimean Tatar, a member of the Turkic language family, just like Uzbek. Mustafayev is still keeping a diary, which he started back in 2018. The Ukrainians’ editorial office has parts of it. Flipping through its pages, one can track how much his handwriting has changed.

In the letter from prison quoted above, addressed to Ukrainian journalists covering persecutions in Crimea, Mustafayev writes: “The aggressor fervently hopes that after years of occupation and massive persecutions in Crimea, those who care about our cause will weaken their resistance, and the world will put the issue of Crimea and persecutions in Crimea on the back burner … Therefore, each member of our profession must take one step after another every single day, write page after page, and prevent this issue from disappearing from the agenda of all international platforms capable of resolving it.”

A difficult choice

The Mustafayev family has four young children: Yusuf, Yunus, Dzhemile, and Nadzhiye. Nadzhiye was just two months old when her father was arrested. When preparing for their most recent extended visit, the family faced a difficult decision about which children to bring along. Russian colony regulations allow only two adults and two children to attend. “With four kids,” Maye says, “deciding which ones would visit their father was tough. In the end, we considered their school grades and sports achievements to make the choice, hoping this trip would motivate them.”

Yusuf and Dzhemile were chosen to visit their father this time. Maye recalls their first visit to the colony three years after the arrest when Yunus, the eldest son, went. “Yunus didn’t recognize Server on his first visit,” Maye says. “He was only seven when they took his father away. The kids rushed to Server when he smiled. They wanted to hug him but were hesitant and unsure how to approach their father. They couldn’t get enough of each other and struggled to find the right words.”

During the first year after Mustafayev’s arrest, his sons played a game of “house search.” They built a prison out of colorful building blocks and “freed” their father.

Even under arrest, Mustafayev actively participated in the Crimean Fig / Qırım inciri writing contest, a literary initiative for poets, writers, and translators. He wrote poems and prose in prison, submitting his texts to the contest. In 2020, Mustafayev wrote and submitted his short story “Yusuf’s contemporary madrasa” for publication. In this text, he reveals that he named his sons in honor of Prophet Yusuf [Joseph in the Bible] and Prophet Yunus [Jonah]. Mustafayev recounts an episode from The Chain of Prophets by Osman Nuri Topbaş, where Prophet Yusuf came out of prison and inscribed on its door: “This place is an abode of evil, a grave for the living, a trigger for enemy slander, and a tribulation for the pious.”

Mustafayev then reflects on his own experience in the prison where he has been held since 2018: “In prison, days and nights pass differently: Some of them drag for a long while, while others fly by.

As I took my first steps into these foul, dark rooms between these walls, my spirit shrank. The people around me, their conversations and behavior, immediately struck me with their ugliness.

The condition of the prison cells, every stone a reminder of its 200-year history. The state of the toilet and wash basin was not fit whatsoever for our religion, where cleanliness reigns. Yet, my mind told me: ‘You must endure; this will be your home for the months and years to come.’ From the first moments, all kinds of insects—fleas, bedbugs, cockroaches— along with mice and rats affected my well-being, as I had yet to get a grip of myself, but my mind persisted: ‘Whether you like it or not, whether you want it or not, this is your trial, your home for the months and years to come.’ These trials from the Almighty befell me and my family in the early days of Ramadan in 2018. The strength and blessing of those holy days helped me adapt to this challenging situation and glean new lessons.”

Presence of mind and commitment

Six months before Mustafayev’s arrest, members of the Crimean Solidarity were in a meeting, deeply engaged in discussing political issues, when Russian police officers and riot police unexpectedly entered. They claimed to have received an anonymous call about an explosive device inside the building. Mustafayev was holding the mic as they opened the door. I remember he was not at the least surprised to see a group of people in uniform. He greeted the police officers and informed the audience about the arrival of “guests.” He urged everyone to keep calm, requested journalists to photograph the officers’ badge numbers, and then simply…resumed his speech.

This text was written in February–March 2024

Translated by Hanna Leliv

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано світлину громадянської ініціативи «Кримська солідарність» із суду, ілюстрацію Марії Глушко та фотографії Олександри Єфименко.