Ukrainian-born, British writer and propaganda researcher Peter Pomerantsev has been working on the documentation of Russian war crimes with The Reckoning Project: Ukraine Testifies since its launch in 2022. He currently lives in Washington, D.C. and frequently visits Ukraine.

Pomerantsev’s renowned book Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: Adventures in Modern Russia (2014) emerged from his experiences living in Russia and working in Russian television for nearly ten years. Peter reveals how the Revolution of Dignity changed his understanding of who can be Ukrainian and that today Ukraine is a country where abstract words mean something very real.

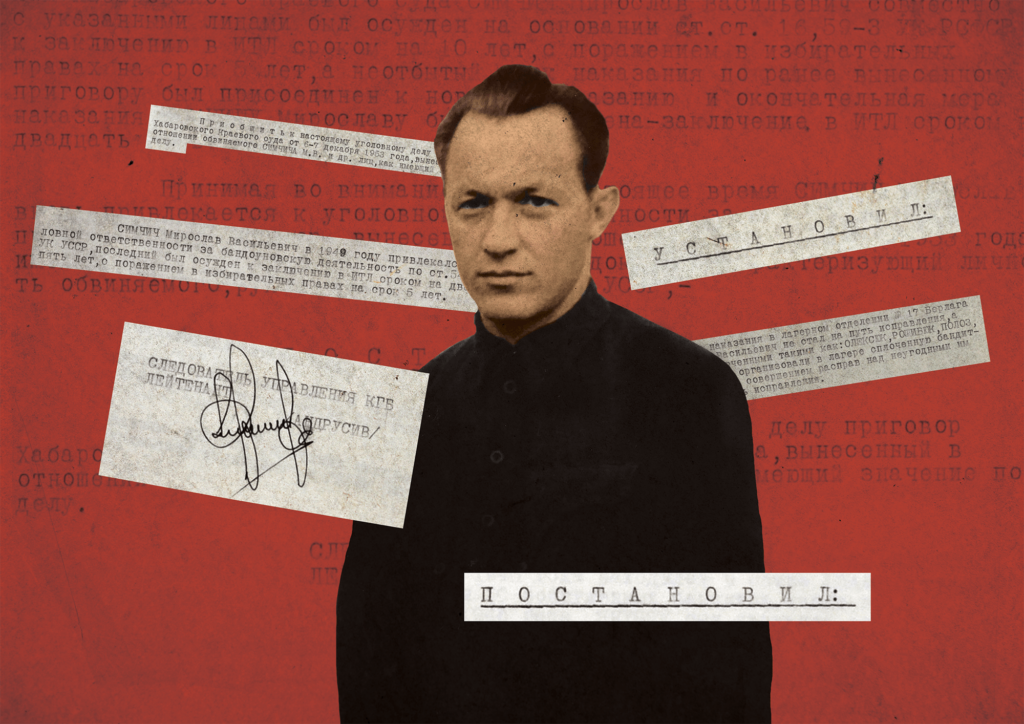

“Politics is always about language, that’s why the famous poet Vasyl Stus is also a political figure, not just a poet. Dissidents in Ukraine played a much larger role in political life than they did in Russia,” says Pomerantsev, elucidating the legacy of Soviet dissidents in today’s war between Russia and Ukraine. Read about how he discovered Kyiv as an adult, the influence of his writer father, and whether propaganda is changing in our conversation below.

Peter, you were born in Kyiv, but you left the city as an infant, when your parents got permission to leave the USSR. How did you develop a relationship with Kyiv?

I was raised with a mythical idea of Kyiv. It came from my parents’ stories. Kyiv is my mother’s native city, my father is from Chernivtsi. My mother was constantly searching for cities in Europe that reminded her of Kyiv. Cities that resembled Kyiv gave my mother peace of mind. Munich was one, with its great big park and colorful buildings. My mother grew up near Holosiivskyi Park, and she needed to have something like it nearby. That was a matter of aesthetics. But there was also history, stories—I write about them in my book (This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality, 2019 –Ed.). Arrests, friendships, interrogations… Kyiv for me was an abstraction, and I hadn’t the slightest idea of what it was really like. I came here for the first time relatively late, when I was around 18.

I feel incredibly relaxed here. I still haven’t figured out why the city has that effect on people who come here.

When did you start visiting Kyiv more frequently?

I’d say Maidan was the turning point, 2014 is when I began spending a lot of time in Kyiv.

Maidan revealed new ways of being Ukrainian.

Of course, I’m British. But that’s when I understood that Maidan had created new opportunities to be involved with Ukraine. I always had them, but I only realized it in 2014.

How would you describe your relationship to Ukraine?

I’ve written a long essay about this. I don’t have a Ukrainian passport. I empathize with Ukraine. When I was in school, people called me Russian, because I was from somewhere around there. But I don’t like it when people insist on calling me a Russian–British author. If you really must, then write “Ukrainian–British.” This is an important distinction for me in certain situations.

A number of your family members come from Ukraine. How did you get to know the Ukrainian parts of your identity?

For me, this process was anything but abstract. When I came to Kyiv and saw the city I realized that my aesthetic sense, which I got from my mother, is from Kyiv. Then I went to Kharkiv, where my grandmother is from. My grandmother was always putting on airs, especially around men, but in Kharkiv I discovered that she was simply a typical Kharkiv girl. All the young women in Kharkiv look and act the way she did, and it was as if, everywhere I turned, I saw my grandmother. Eventually I made it to Odesa, where a lot of my father’s family is from. And in Chernivsti I discovered that my father’s imagination and cosmopolitan worldview, his sense of humor, are all from there.

I saw the textures of everyday life that I knew from my family, which I thought were completely private, in Ukrainian cities. It turns out they are absolutely integrated into local culture.

So I can’t really say that I discovered my Ukrainianness on these trips, but rather that I discovered very specific things. Later on, when I was exploring my personal relationship to Judaism, I realized this is also a very Ukrainian story. Ukraine has a long tradition of Hasidism, which has its own, particular kind of storytelling. The traditions of Ukrainian Jews are deeply rooted in Ukrainian folklore, which certainly had a serious influence on them. I’ve never been good with abstract concepts, so I’d rather speak in very concrete terms.

There are abstract terms like hero, country, army, war. That we can use these words now is a sign of wartime. But a country and your sense of it always begin with concrete things. Look, I was shocked by Kharkiv. I’d been to Kyiv as a young man, but it was only after Maidan that I went to Kharkiv. I had no idea what to expect, and what I saw was the image of my grandmother.

Private things are always part of something very big. This personal knowledge makes you realize that you are part of something bigger. And that gives you strength, because the better you know yourself, the more control you feel like you have over your life, and that means more freedom.

You write a lot about the return of meaning to hollow words. How did Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine activate this process, particularly when it comes to categories that the West values?

For a lot of people, politicians as well as ordinary citizens, the very expression on Putin’s face on the eve of February 22 was a revelation. At that moment many of us realized that the invasion will happen, these are not mere words. It all sounded so terrible that it was hard to believe, and yet it was real. And the politicians’ reactions were not contrived, but sincere. People don’t usually go into politics for the money, they do it because of a certain romantic idealism, even if they become cynical later on. Some of them really do have a strong sense of justice. Europe was created to prevent the existence of a police state. The situation posed by Russia’s invasion was plain as day. The question at the outset was clear: what if Putin wins and democracy loses? Democracy won in the 20th century, but we paid a very high price. Another thing is that we always need post-victory stories. Post-1945, post-1991. And we forget that before victory was achieved, the outcome was completely uncertain.

There’s been a lot of talk about Ukraine fatigue lately. Is this something you’re worried about? Does it affect your work?

People are tired everywhere, both here and abroad. This fatigue is normal. War is tiring and things cease to amaze you. Fatigue is not visibly affecting support. I am much more worried about exhaustion. That’s another story. Exhaustion sets in when we feel like what we are doing is pointless. Whereas fatigue you can combat with sleep; when you know that you’re doing the right thing, and you see results, you just need to recharge. Now exhaustion is dangerous. It’s different from fatigue and boredom. People overcome fatigue and exhaustion by having a goal, when they are sure their efforts come from the right place and have a clear aim.

Exhaustion worries me—not because people may start to question why they are doing what they are doing, but because they might lose sight of their objective in supporting Ukraine. That’s what’s dangerous. People may still have energy, but they’re emotionally exhausted. It’s like depression. Depression sets in when you don’t understand where you’re going anymore.

Do you feel exhausted by Ukraine at this point?

I’m not sure, it’s not something I’ve seriously examined. I’m certainly tired, which is only natural. What we know for sure is that in America, and I suspect it’s the case in Europe as well, support for Ukraine is directly proportional to believing that Ukraine can win. It’s about a feeling in the present moment. Of course it’s related primarily to victory on the front lines; however there are other kinds of victory we can also work toward achieving: responsibility, accountability, justice, reconstruction. We need to think about victory in many different ways. Victory means breaking Putin’s system.

What happened around the explosion of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant was very significant. The response should have been immediate: this was a serious crime, ecocide, a man-made industrial disaster. Instead the initial responses were opaque and ambiguous. Remember how everybody was thrilled to be fighting for democracy? Well it turns out that democracy does not always win. These are the kinds of situations that breed exhaustion, and you start asking yourself: what if evil wins and we have to live with Putin forever? This feeling that people like him will remain in power and will keep doing similar things just because they can… it’s real.

What stories from Ukraine should we be telling?

There are a lot of ways to tell stories about these different aspects of victory. We really need more of these sorts of stories. I work with a large project that documents Russian war crimes, and our team’s job is to make these crimes clear to people abroad. Another way to tell Ukrainian stories is through culture. Art offers a much deeper level of engagement. People love stories about Ukrainian culture because it has persisted under the most difficult circumstances.

We are anticipating a big victory at the front, we just don’t know yet when it will come. To achieve victory we have to start telling a lot more stories, and this is the job of journalists. From rebuilding villages to economic justice, while at the same time exposing Putin’s networks in Europe… There are many people who can tell these stories.

It is our responsibility to extend this moment when there’s a feeling that Ukraine is winning.

We’ve all been talking about how the West’s attitude toward Ukraine has changed. What do you think was the breaking point?

Kyiv was surrounded. Ukraine succeeded in defending itself and protecting Kyiv. This was a transformative moment.

Ukraine fought like a big family, with everyone supporting each other. The civil society was fully involved. We had been talking a lot about sovereignty—in the abstract—and here all of a sudden we see a nation fighting to defend its sovereignty. It had an effect on liberal democrats, to see a society willing to fight to defend liberal democracy. It had an effect on everything. Things we had debated abstractly, empty phrases, were happening in Ukraine in real life. Ukraine was the place where words that no longer mean anything in the West suddenly became real.

After that everybody began to take a closer look at the country’s culture and history. Ukraine had become an actor.

Before that the country had been treated as something passive, at least in the English-speaking world, like an empty space for projections of the worst things: corruption, Nazis… Take the worst you have at home and project it onto Ukraine.

But this is precisely what happens if you don’t talk about your history—loud and clear. That’s what cultural diplomacy is for. There is a concept called reputational security, which assumes that the idea of soft power is outdated. Reputational security is far more aggressive, requiring constant work in the diplomatic sphere as part of a broader security strategy. Even vulnerable nations under attack can survive and be heard if they work on reputational security.

Telling stories from Ukraine was a challenge before 2022, as very few people were talking about decolonization in the Russian context.

It was different in different countries and in different fields. Back in 2010–2011, I wanted to write about how Ukrainian literature was changing for a certain literary magazine. I pitched them a story about emerging Ukrainian writers, like Serhiy Zhadan, Sofia Andrukhovych. There was no interest. I said, “Look, this is the birth of a new literature, it’s exciting!” Still, there was a lack of Ukrainian literature available in translation, which they pointed out, although it wasn’t nothing.

Western intellectual circles, which did not pay heed to Ukraine’s appearance as a force on the cultural map, also share responsibility for the situation we are in today,

I am not blaming literary magazines for russia’s invasion. But there is no doubt that those groups in the West responsible for cultural representation decidedly failed. However, Ukraine didn’t do enough as far as public diplomacy either.

How could people working in the diplomatic sphere use the country’s new image to generate, say, greater interest in researching Ukraine in the field of Slavic studies?

I work at a university, but not in Slavic studies, so honestly I don’t know. But I do see that things are changing and debates are sprouting up. Universities are slow to change. Academic institutions, publishers, journals, each in their own way, have all been part of the process of centering Russian culture, highlighting Russia and leaving Ukraine, the Baltic countries, Central Asia and Georgia in the shadows.

Do you have a desire to revise the way things have been done? After all it’s a matter of changing attitudes that hundreds of people have believed in and built stable careers upon.

We ask these questions all the time. I can offer some examples from Great Britain and the US, where I know the situation better. For instance, we still love Jane Austen, but where did all those people in her novels get their money? From somewhere in the British colonies. And so we are constantly reexamining our entrenched ideas. The same goes for Churchill. He was a hero for three generations, although his biography is horrendous. I don’t understand why it should be so difficult to apply a similar approach to Russia. But this is also a matter of maturity, because maturity is what allows us to not fetishize something, such as Russian literature.

What do you think a decolonial reading of Russian culture should look like, practically speaking? Are there specific things that are missing from the discourse?

There is still a tendency to consider Russian culture outlandish, as something with an inherent mystical beauty. We need to demystify it. On the one hand, Solzhenitsyn is a brave and important author; on the other he is an absolute imperialist. Churchill was an incredible wartime leader; at the same time he was a racist and an imperialist. Is it really that hard to refrain from romanticizing and to put things in context? In the English-speaking world we constantly apply this intellectual process toward ourselves, so I find it strange that we don’t apply it to Russia as well.

Russia has a history of self-destruction; it is pretty evident to the Russians themselves, just read any of Sorokin’s novels. Meanwhile Western intellectuals keep asking, “But what about Solzhenitsyn? Dostoevsky?” These figures serve to reaffirm truly horrific traditions. There are intense debates going on in the US about the founding fathers, who established democracy, who fought for freedom, who were slave-owners and who did not take issue with slavery.

The idea that the same person can be for certain rights while completely disregarding other rights is not a new paradox. Sure, we take issue with Jane Austen, but we don’t reject her.

How do we counteract the false narratives spread by the Russian humanities, when you can still hear the absurd claim that Ukrainian literature is primarily written in Russian and other untrue stereotypes?

This is a question that everyone fighting against propaganda asks themselves. How do you fight propaganda without amplifying it? This is the problem of Trumpism and Putinism. You should always start by answering the question: who is your audience and what do you want to tell them? You always have to think about your audience, don’t just react to the propaganda. Sometimes the audience is uninformed, then it’s worth providing them with accurate information. Sometimes you can actually use the propagandists, but make sure that you are using them and not the other way around. Because propagandists always anticipate a response.

How can you use propagandists?

You should never respond to their questions and accusations. The moment I start responding to the propagandists, I’ve lost. It’s important to address the audience directly. Then there’s a chance that your important message will actually be heard.

But there are more serious things. You have to specify your aims and understand exactly what you want to achieve.

Do you see new challenges to communications in this war?

Communications tactics change with the development of new technololgies. You always have to keep an eye on the commercial sector—things like AI and deepfake technology. I don’t really think about it too much, because there’s always something new coming out and we just adapt to it. Everyone was so worried about deepfakes, but this hasn’t ended up being a huge problem. And now everyone’s worrying about chat GPT.

Have you noticed the development of new expertise in countering Russian methods?

Everything about this war is interesting. First of all, Ukrainians have made a convincing case that propaganda can be used toward good ends. Zelensky has shown that you can be more effective than your foe when you are sincere, emotional, when you address your people and tell the truth.

There’s been paralysis since Russia, China and ISIS began using information technologies, like troll farms and disinformation, against liberal democracies.

We all thought that good journalism was the answer, but this [combating disinformation] is not journalism’s job. And journalism is often implicated.

Ukraine did not invent this practice. Greenpeace has used propaganda techniques for years to get their ideas across, and to great effect in Europe. But the leaders of democratic countries still aren’t comfortable with this kind of communication, using social media every day, and constantly addressing their citizens directly. It had never even occurred to them. I hope that democracies will adopt this approach, now Biden is following Zelensky’s example. The West used to do this wonderfully, think back to Churchill, but then they stopped. We’ve become very modest in our use of mass communication.

Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba says that Ukrainians should learn to export their information expertise. What are your thoughts?

First we have to win the war. But yes, it’s true that Ukraine is at the forefront of the most unprecedented use of information operations in war, and you can export all this afterward. My wish is that all the innovations that Ukrainians are developing today will ultimately be used for good.

How does war affect freedom of speech?

The same question comes up all the time: how can we be consistent and prevent the constant circulation of rampant disinformation? If we take a historical perspective, look at the history of Great Britain during World War II. There was a real media war going on.

The paradox with freedom of speech, as the British discovered then, is that people have to trust the government. This means that you are constantly seeking a balance between trust, which is important for keeping up people’s morale during wartime, and maintaining discipline, which is essential in war.

If you simply consolidate the flow of information and don’t provide any bad news from the front, then people will lose their trust in you, which also affects morale. The BBC made an important decision in 1941—to start telling the truth about British losses. This helped the British to maintain a degree of self-criticism, thus preserving their trust in the decisions of their leadership and social solidarity. After all, solidarity is more important than the ability to produce fake news.

In your book This Is Not Propaganda you write a lot about your father Igor Pomerantsev. How does the story of this 1960s-era dissident poet help you explain the essence of propaganda?

My father really is one of the main characters of the book This Is Not Propaganda.

Basically, I am trying to describe a situation that deprives you of liberty and limits your ability to be free and belong to a united community. But I write about how facts and good journalism are not enough to beat propaganda, although they are important.

I wanted to write about a poet’s interaction with the Soviet propaganda machine in a historical context. Soviet propaganda was about the masses, and it tried to wipe out individualism through various means, which were sometimes brutal, and sometimes exquisite. Writing, and thus continuing to create genuine art, was the author’s act of resistance. When Igor later emigrated to the West, in the 1980s and 1990s, he found he had less and less need for this mode of writing about himself. For in the West his individuality was no longer threatened, and individualism as an issue had become commonplace.

Look, in the age of social media everyone can imagine being a 1960s individualist. It’s actually an interesting phenomenon: the more we think that we are showing our true selves in social media, the less we are actually being ourselves.

Igor’s writing changes, as freedom is no longer contingent on loudly shouting “I!” and he starts experimenting with other things. I am interested in this constant competition between art, poetry, propaganda and freedom. Something that has power in one context can be absolutely ineffectual in another. Poetic language changes with respect to poets always being the first to sense subtle shifts in the language of the public sphere. All of this is always about freedom, it’s just that there are different roads to freedom.

How do you view the legacy of the dissidents in Eastern Europe today?

I think they’ve left a much greater mark on Ukraine than on Russia. Someone recently asked what I think about the Russian intelligentsia. I think it’s a myth dating back to the early 1990s, which described the existence of an intelligentsia that transmits its values to society. If such a thing ever existed, then it has completely disintegrated. There really was an anti-Communist movement in Russia during the Soviet era, but Russian society never developed the desire or need to understand itself and to grant those people greater authority. After the USSR collapsed, Russian dissidents had no real influence on political life.

In Czechia, there was Vaclav Havel, who became president. You [in Ukraine] had Chornovil, for example, and while you did not elect him, he remains an important figure. Your dissidents played an important and practical part in keeping the Ukrainian language alive. Politics is always about language, that’s why the famous poet Vasyl Stus is also a political figure, and not just a poet. Dissidents in Ukraine played a much larger role in political life than they did in Russia. Dissident poets in Russia never came to symbolize the country’s political ideals.

What was it like for you growing up with a writer father? Did he teach you particular reading habits?

It was awful! (Laughs.) Dad wanted me to be a little Mozart. When I was 4 or 5 years old, every week I had to learn a poem by heart! Also, every week Dad would stage a poetry-writing contest where he would give me a topic or metaphor and I would write. Once when I was 10, I came to Dad in tears. He had told me that all children read poetry, but I discovered in school that that’s not true! Since Dad forced me to write poems, that pressure gave rise to an aversion. So I rebelled—and that rebellion led me to film and television.

What about your mother’s professional interests?

Yes, I enrolled in film school. I started writing later on, after asking myself again what I really wanted to be doing. Writing in English is a way of defending myself, because I feel like I could be swept away by the power of this language. I am the child of immigrants after all. Every time it’s a struggle to assert my voice in this language. Writing helps me work through problems and crises. When I can write about them, it gives me back a sense of control. Reading as a child did in fact have an effect on me and on my relationship to writing. But I still tried to rebel.

What books, as in works of literature, have had the greatest influence on your writing?

Since I’ve been writing nonfiction over the past several years, I’ve been reading a lot of historical books. I think my next book will be a novel based on witness testimony. So I do have a need for more fiction.

But if we’re talking about the authors who truly changed how I look at things… The Rings of Saturn by W.G. Sebald is one. I tried to imitate it, but I think that I failed! Sebald shifts from one theme to another in an incredibly subtle way; in the texture of his prose the past never recedes completely. I am trying to do this in my new book.

New Journalism [1960s–1970s American literary movement, incorporating a subjective view and literary devices into news reporting — Ed.] has had a big influence on me. Of all its writers, its most classic authors, above all Gay Talese, have left a lasting mark on me. He wrote literary journalism. And finally The Moscoviad by Yuri Andrukhovych. I had several books on my mind, and this novel in particular, when I was writing Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible.

Did you feel like the hero of Andrukhovych’s novel?

No. Andrukhovych is trying to show Moscow’s insanity from a different angle than I was. The Moscoviad is a classic post-colonial novel about a post-colonial subject. After all, his Moscow is in the early 1990s, while mine is in the 2000s. What’s interesting is how different our books are. Yuri writes about what is falling apart, while I write about its horrific return.

Why do you read?

I read to understand how other people deal with their doubts and problems.

When is your next book coming out?

My new book (How to Win an Information War: The Propagandist Who Outwitted Hitler –Ed.) will be out in the UK in March [2024]. It’s about World War II and this whole campaign of undermining propaganda. The book focuses on the Nazis but I make comparisons to Russia, the US, and other regions.

I started writing it before Covid. And then the war arrived.

Translation — Larissa Babij

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]