December 1, 1991. A wet, cold Sunday. People head to the polling stations — school gymnasiums, village clubs, houses of culture.

On their way, they talk about the August Coup. The images of AFVs on the streets of Moscow are still fresh in people’s minds. Some discuss the miners’ strikes or the students pitching tents in the center of Kyiv, on the spot that would be known as Independence Square in the future.

This was not a run-of-the-mill election. This time, the choice on the ballot was “Yes, I confirm” and “No, I reject” regarding the Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine. That choice would be consequential for our future way of life and the country in which our children would grow up.

The only thing our people could believe in

November 1991. In the village clubs, where just yesterday the main topic of conversation was potato prices, people talk about politics. On the markets, in the queues, at the kitchen tables, one question gets raised: What will happen to Ukraine? Will Ukraine come into being?

“The Kremlin could imagine the new USSR without the Baltic countries, without Moldova, even without Georgia,” says historian, author of the book “How Ukrainians Destroyed the Empire of Evil” Oleksandr Zinchenko. “But not without Ukraine.”

The Soviet Union was falling apart from the inside. Poverty, inflation and a deficit of goods — all this was par for the course. But even that status quo had its limits.

“The referendums held in the Baltic republics — Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — served as an example to us,” explains writer, politician and diplomat Yuriy Shcherbak. “Those were the referendums on the withdrawal of these republics from the Soviet Union. And we must remember that, even as they were conducted under Soviet rule, they had strong results. For example, in Latvia, 74% of people voted to leave the USSR and in Estonia, 83%. All this happened literally on the eve of Ukraine’s declaration of independence. And, of course, it had an impact.”

Yuriy Shcherbak, a USSR deputy, often traveled to meet with voters. He says that the impending collapse of the Soviet Union was evident to everyone. People clearly understood that this country could no longer continue to exist.

“You know, it was just embarrassing: I remember meeting with voters, with Ukrainian citizens, and they would ask me, ‘Where do you get your socks? Your underwear?’ Today, we can’t imagine what it’s like to see shelves in stores completely empty,” Shcherbak recalls.

Sociologist Yevhen Holovakha confirms this and recounts how he used to bring buckwheat, millet and oil to his aunt in Moscow. He bought it all at triple the price at a market in Kyiv.

“Back then, there was a ration card system. You were allowed to get some oil, some bread, flour and the most basic goods. And, of course, people believed that this was because of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union could no longer provide for the vast majority of the population.”

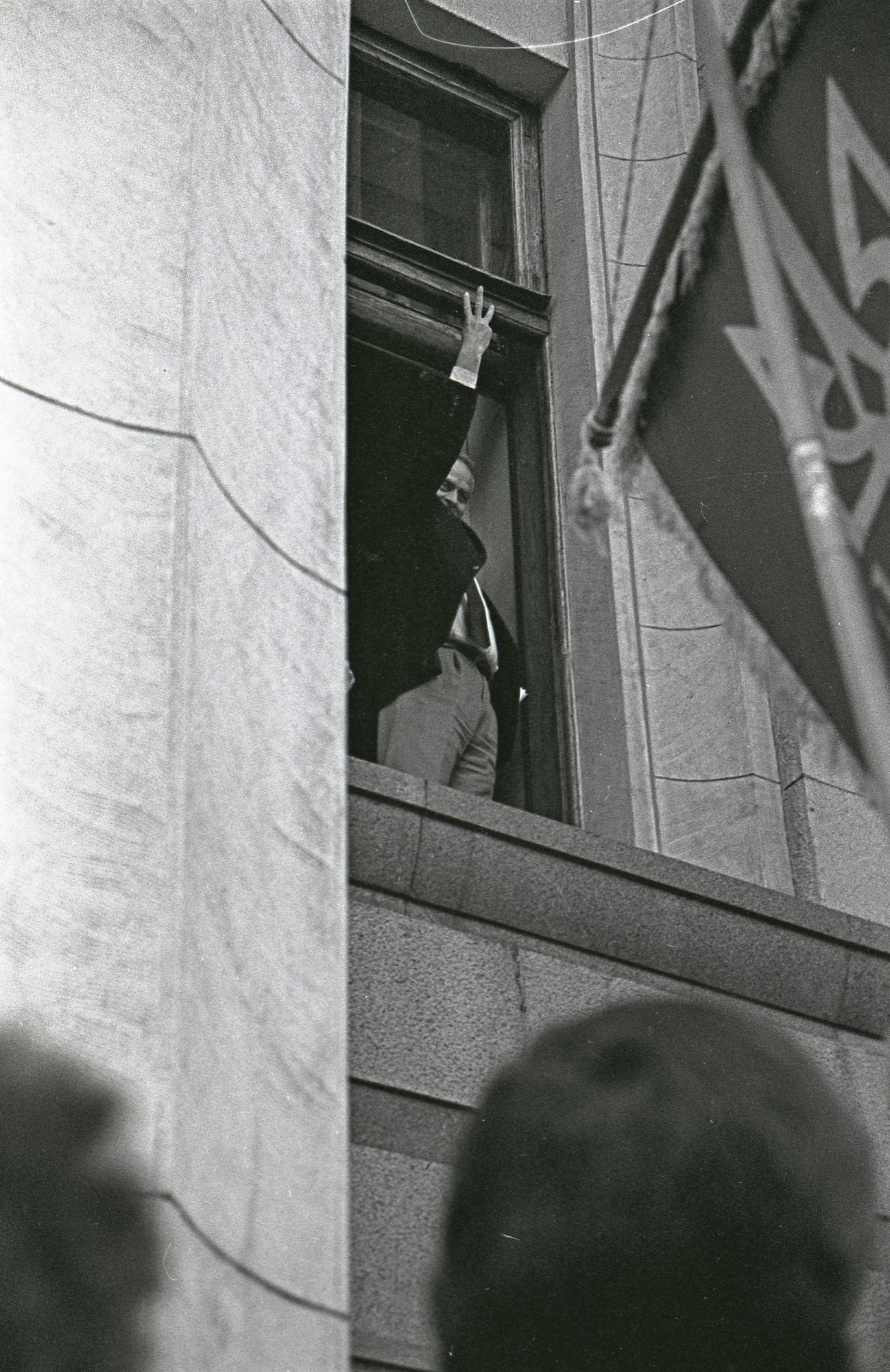

In the 1990s, moods changed rapidly from one extreme to another. What seemed unthinkable yesterday became reality today. A blue and yellow flag was flying again in the center of Kyiv — on July 24, 1990, it was raised above the city council building. And behind the scenes in parliament, a member of the People’s Movement was embracing a man from the Soviet system: they were Vyacheslav Chornovil and Ivan Plyushch, acting chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian SSR.

“Plyushch stops me in the hallway and says, ‘Vyacheslav Maksymovych, come in for a chat… You know, I think the only thing our people can still believe in is complete state independence! And may it be so…’ I said, ‘Ivan Stepanovych, you are a precious man! I could hug you right now!’ It seemed that something had happened to change his mind,” recalled Vyacheslav Chornovil when describing the collapse of the Soviet Union on March 10, 1996, in an interview with Marta Kolomiyets.

Historian and author of the book “How Ukrainians Destroyed the Empire of Evil,” Oleksandr Zinchenko explains that the path to independence was not smooth and instantaneous, but consisted of several successive acts. First came the people who fought for Ukrainian independence for decades: Levko Lukyanenko, the Horyn brothers, Vyacheslav Chornovil and others created an environment that eventually grew into a political force.

“This environment shaped the opposition wing in the Verkhovna Rada. But they were not alone. They won over part of the communist elite with this idea. That was the first act. The second act was the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. The third was the referendum. The fourth was the cementing of the people’s vote in reality.”

The referendum was set to take place on the same day as the election of the first president. The Democrats made this decision when they passed the Act on August 24, 1991. Academic Ihor Yukhnovskyi proposed the idea.

He understood that for the country to truly become independent, it was not enough for parliament to want it — millions of people had to voice their support for it.

“The fate of Ukraine was decided at the referendum,” says Shcherbak. “The Verkhovna Rada’s declaration of independence would have been insufficient had it not been confirmed by millions and millions of Ukrainians. And that is why I believe that this referendum was of global historical significance.”

Witnesses to the Declaration of Independence consider Yuhnovskyi’s idea to be both simple and brilliant. Moreover, on the eve of the referendum, Ihor Yuhnovskyi himself clearly argued on the air of a Kyiv radio station: “Independence is the natural state of every nation.”

Enough

Why do we need independence? Why should we vote? In the fall of 1991, these questions were being asked all around Ukraine — from the mining towns of Donbas to the villages of Crimea. Mykhailo Kosiv, one of the founders of the People’s Movement, traveled around the Chernihiv Oblast, Donbas and Crimea at that time.

“Let’s imagine that we accepted and approved this act, even with a constitutional majority in the Verkhovna Rada, but then there could still be people who would say, ‘But this was Bandera’s slogan.’ Obviously, an independent, united Ukraine sounded like Bandera’s slogan, invented by the nationalists. But after December 1, no one could say that anymore, and no one did.”

Mykhailo Kosiv admits that at first he did not want to travel anywhere, but at that time, he was a representative of presidential candidate Vyacheslav Chornovil, so he had to.

“I resisted and tried to get out of it,” he smiles. “But Chornovil simply pushed me out. I said, ‘Wait, what am I going to do out there? This is not my element.’ ‘It will be okay. You know how to talk to people, and you’ll find common ground.’”

In Luhansk, Mykhailo Kosiv went to the market. There were two bunches of garlic on the counter, one for one ruble and the other for one ruble twenty.

“I asked the old woman: What’s the difference? And she said to me, ‘Because this one’s a Muscovite!’” he laughs. “Why a Muscovite?” “Because it’s nasty, like a Muscovite. This one is milder — the Ukrainian variety.” I then understood that these deep historical and national foundations, laid down over centuries, have not disappeared; they still exist here.”

Mykhailo Kosiv had several meetings every day. In the town of Sribne, in Chernihiv Oblast, he was asked where he was from. He said he was a deputy from Kyiv. But he quickly clarified that he was not originally from Kyiv but from Lviv and was born in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.

“So,” laughed one of the locals, “for the first time in my life, I’m talking to a real Banderite.”

The conversation lasted two hours. People were interested in everything: what kind of independent Ukraine he was advocating for, what it would be like, and how people would live in that independent country. They asked direct questions, not mincing any words. That’s how the meetings were back then — honest, emotional, filled with both distrust and hope.

“The slogans were, ‘Enough’, ‘We’re fed up’, ‘No more Afghanistans.’ This was the basis for the preparations for December 1. Aren’t we tired of subordination? We are tired, very tired. Why should someone in Moscow appoint our government when we could build whatever we want on our own land? And there was another slogan, especially well remembered in Donbas: ‘We are tired of being the stokehold of the Union!’”

They had three months and one week for campaigning. Kosiv says that they sought out incentives for each region.

“Can you imagine? They bring me to the deck of a ship. The crew gathers, and I talk to them. And they also want Ukraine. It feels closer to them. After all, the entire Black Sea Fleet consisted of three categories: Ukrainians from mainland Ukraine, Ukrainians from the Crimean Peninsula, and Russians who had been sent there. But they didn’t even make up a third of the fleet, so they couldn’t play a significant role. And so for me, there is no doubt that the Crimean Peninsula was, is, and will be Ukraine.”

On December 1, Mykhailo Kosiv and his wife, Marusia, traveled to the capital to vote. For him, it wasn’t some kind of special day — the campaign headquarters was still bustling with activity. The last three months had flown by. However, the priority during the vote was the question of Ukraine’s independence.

“We were checking voter turnout every hour,” he recalls. “Marusia had to drag me away to get something to eat. But food was the last thing on my mind. All I cared about was the events that were unfolding.”

Quietly, from under the hem

Andriy Saliuk, a Lviv native and one of the leaders of the Revolution on the Granite, who until recently had been pitching tents on Zhovtneva Square and protesting alongside other students, now traveled with friends to the Vinnytsia region to campaign. And these were not just conversations about politics.

“People perceived us much more favorably when we not only spoke, but also did something,” recalls Saliuk, who was then the head of the Lviv Polytechnic Student Brotherhood. “When they see that you are actually doing something with a shovel or a pickaxe, they are more willing to listen.”

First, the brothers restored the graves of Sich Riflemen in Lviv Oblast, and later those of Cossacks in Vinnytsia Oblast. This work, he says, made a better case to the people than most rallies. However, their arsenal included not only shovels, but also guitars. The Student Brotherhood’s singing group traveled around villages with concerts: they performed riflemen’s songs, rebel songs, folk songs. And after the sing-alongs, there were books, newspapers, samvydav — information that the Soviet Union tried to conceal.

“At that time, Radio Liberty in America reported that the KGB wanted to expel some students from Vinnytsia Oblast,” Salyuk smiles. “The KGB and the prosecutor’s office constantly created problems for us — quietly, behind the scenes. They didn’t allow us to do anything, they blocked us, they blacklisted us, they expelled us by force.”

However, the students managed to enlist the support of the locals. Their own information campaign unfolded between fields and villages, between literature and songs.

“We arrived in Bratslavshchyna,” recalls Saliuk. “And they said to us, ‘Hey, why did you come? We don’t need to be persuaded anymore. We know what we have to do.’”

It was the same with other student groups who returned from trips prior to the referendum. They heard the same thing everywhere.

“Everyone said, ‘We’d arrive, but we didn’t even need to campaign. They already knew why they would be voting for independence,’” says Saliuk.

The Student Brotherhood’s trips were not in vain. They did their homework in advance when, in the early 1990s, they restored the graves of the riflemen and the Cossacks in various regions. On election day, students rushed to the polling stations to gather together as a community and plan their next actions, events and activities.

Zero hour

December 1. Sunday morning. In the east and west, in cities and villages, people are going to vote for something that seemed unattainable just a few months ago — Ukraine, not as an idea on paper, but a real possibility. The cameras are capturing it. Khmelnytskyi, regional philharmonic hall, polling station No. 58. 11 a.m. A third of the voters have already cast their ballots — 650 people.

“People understand what they are voting for — for autonomy, for independence — and people are coming out, young and old alike,” comments Yuriy Krulikovsky, head of polling station No. 58, dressed in a vyshyvanka and a jacket, in archival video footage digitized by Suspilne. “A lot of people come and thank us for the fact that the polling station is available and they can cast their vote.”

The voters are focused and taciturn. Journalists interview them on the streets. People do not avert their gaze or mince their words, but they wrap themselves in coats. In a social video about the nationwide referendum and presidential election, voters on the street talk about whether they voted and why. The answers and arguments vary. Here is one of them.

“Did you vote?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Which way?”

“For independence. That’s the only way to get out of this mess.”

“How will you benefit from it personally?”

“I don’t need to benefit personally. We need to be reborn as a nation. As a state,” says the man in a suit, tie and hat.

After lunch, the polling stations are crowded. There are queues. People come out of the booths, sigh, smile at the camera and remain silent. Voting continues. In Kharkiv, student and singer Maria Burmaka excitedly ticks the “yes” box.

“Back then, I think, 86% of Kharkiv residents voted for independence. Everyone understood that Ukraine was a colony, and now there was an opportunity to go our own way and build our own state. It was all about, you know, as Khvylovyi said — getting away from Moscow.”

When the results were being announced, Maria held her breath. Student hunger strikes, protests, nervous anticipation. Finally, the day had come that would put everything in its place. “Justice prevailed” — that’s how she describes the choice that had long been obvious to Burmaka herself. It was what she fought for, spoke out for and sang about.

“When my father and I spoke Ukrainian, people would mock us in Russian, ‘Such cultured people, but speaking Ukrainian,’” Burmaka smiles. “I think that many factors influenced the mood of the people, especially in Kharkiv. Why did this happen? Kharkiv is a city of intellectuals, where culture was born and where it was murdered. The Slovo House. The poets and writers of the Executed Renaissance. Rebellious sentiment has always existed in Kharkiv.”

Maria recalls how, in 1989, she arrived from the Chervona Ruta music festival and was warmly welcomed by the student and professorial communities. And not only by the Ukrainian wing of the linguistics department at Kharkiv University, but by others as well.

“After that, I was summoned to a certain department and asked about the song I’d sung there — ‘Oh, do not blossom, spring, my people are in chains.’ Something like that happened. But no special sanctions or actions were taken against me. I think it’s because these internal movements were already noticeable in Ukraine, and there was noticeable support from both students and teachers.”

1. Dismantling of the Lenin monument on Independence Square in Kyiv. September 12, 1991 / 2. The dismantled head of Dzerzhinsky, the leader of the “Red Terror” and the violent establishment of Bolshevik dictatorship. His monument was removed from in front of the former KGB building in Kyiv. Like Lenin’s, it was taken to the grounds of what was then the Museum of Kyiv History. 1992

On the eve of the referendum, journalists from the Ukrainian television youth studio “Hart” conducted street interviews in Donetsk, Lviv, Odesa and Kirovohrad. People spoke simply and honestly. In Donetsk, miners — the same ones who had been striking for years, fighting for economic dignity — wanted to vote. Strike committees in Donbas had not yet ceased their operations. They were waiting for concrete decisions from the new, independent Ukrainian government. They had long since stopped trusting the central power in Moscow.

“I believe that the more rights and opportunities we have for trade and economic development, the better it will be overall,” says a miner in Russian in archival footage from the Gorky Mine in Donetsk, where about 4,000 people were working at the time.

“Independence and nothing else. We need to live like human beings. How long can this go on?” adds another miner, also in Russian.

Similar sentiments were echoed hundreds of kilometers away in the village of Dobrovelychkivka in Kirovohrad Oblast, home to 7,000 people:

“We are Ukrainians, we will vote for Ukraine.”

“For independence. It’s like a big family, like my parents had — there were eight of us, and we survived somehow. But if you have just one child, or two, life is different. That’s how we lived in the Union…”

“Life in the village is not great. If you compare it to what they show on TV — they recently showed small towns in Finland… If we had done this earlier, maybe we would already be living like they do in Finland. But all is not lost. While there is still a chance, we must seize it.”

In the center of Kyiv, at a polling station in the building of the National Academy of Sciences near Besarabka, Yuriy Shcherbak, who in three years will become Ukraine’s ambassador to the United States, goes to vote with his family.

“Bush made a statement that if the referendum in Ukraine ended positively, that is, if there were convincing figures regarding the Ukrainian people’s desire to move toward an independent Ukrainian state, the United States would support Ukraine’s independence. It came out of the blue. An angry Gorbachev began calling Bush. What are you doing? You are destroying the Soviet Union. But that was the decision made in Washington and the White House,” explains Yuriy Shcherbak.

On that day, more than 90 percent of Ukrainians voted for independence. The turnout was 84 percent. Nearly 32 million people cast their ballots.

“I am a sociologist, after all,” smiles Yevhen Holovakha. “And at that time, I knew very well how everything would end, both the referendum and the presidential elections. We conducted more than one poll. The only thing that remained in play was Crimea. Crimea was a mystery, that’s true. Although all the polls, including ours, showed around 52-53 percent in favor, that was no guarantee that it wouldn’t be 47-48 percent, taking into account certain errors, circumstances, and events that could influence the outcome.”

According to him, in the early 1990s, society was filled with extraordinary faith in the future. People sincerely believed that Ukraine was the richest republic, and that once it became independent, everything would immediately flourish.

“But by April 1992, journalists were coming to me and asking, ‘So where is this improvement? Why isn’t anything changing?’ I had to explain that social transformation is not an instant process, especially in post-Soviet countries.”

At around 10 p.m., the first official results begin to appear, “yes” votes so far prevailing. The country freezes in anticipation. Televisions glow in apartments, kitchens, and dormitories. In the center — Kyiv, Cherkasy, Poltava — over 90% in favor. Even in the east — Luhansk, Donetsk — more than 80% in favor. In Crimea, too — the majority in favor.

“The idea was simple,” explains Yevhen Holovakha. “A better life. For ourselves, for our children. So that we no longer work for someone else, but build a better life for ourselves in our own home.”

I will listen to my people

Leonid Kravchuk won the presidential election. Vyacheslav Chornovil lost to him, winning a majority in only three regions: Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil. Why did this happen? Sociologists have the answer.

“In essence, the national idea embodied by Chornovil, Kravchuk’s main rival, was the deciding factor only for a quarter of the population, mainly in the west. In Kyiv, it was for about 40 percent. But overall, it wasn’t the main issue for the voters. We also conducted surveys in villages, and there was no one there who said, ‘I want my own Ukraine.’ The sentiment was more like this: Why do we need Russia? We are on our own. We will be better off. We are hard-working, and they’re all drunks. This was a very common argument. Some people had served in Russia — in Vyatka, in Vladimir — and saw how people lived there. Others heard about it from someone else. And everyone came to the conclusion: we will be better off on our own,” sums up Yevhen Holovakha, who at the time was head of the sector for the democratization of society at the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences.

Radios crackled with the news, televisions showed the first broadcasts, and people called each other, asking one question: how many? And on the morning of December 2, The Guardian published a fresh article: “Ukrainians yesterday voted overwhelmingly for their republic’s independence, killing off any last chance that the Soviet Union can survive as a political union.”

The referendum was the final nail in the coffin for the empire. According to historian Oleksandr Zinchenko, in this way, Ukrainians made the decision for everyone else. Every day after December 1, country after country began to recognize Ukrainian independence: December 2 — Canada and Poland, December 3 — Hungary, December 4 — Latvia and Lithuania. On December 8, the leaders of Ukraine, Russia and Belarus met in Belovezhskaya Pushcha, signed an agreement, and the Soviet Union legally ceased to exist.

Kravchuk responded to Yeltsin very clearly and diplomatically, as quoted by Oleksandr Zinchenko: “Boris Nikolayevich, imagine that you are in my place. Your people have voted for independence, while you are being offered a new union treaty. Who would you listen to — Gorbachev or your people?” Yeltsin smiled: “My people, of course.” “Then I will listen to my people,” replied Kravchuk.

The choice made on December 1, 1991, seemed like the end, but in fact it was only the first line in a new chapter. Thirty years later, Ukrainians are once again fighting for independence — in the trenches and diplomatic chambers. And the question “Who are you?” looms just as large as it did then, under the gray December sky, when people went to the polling stations to vote.

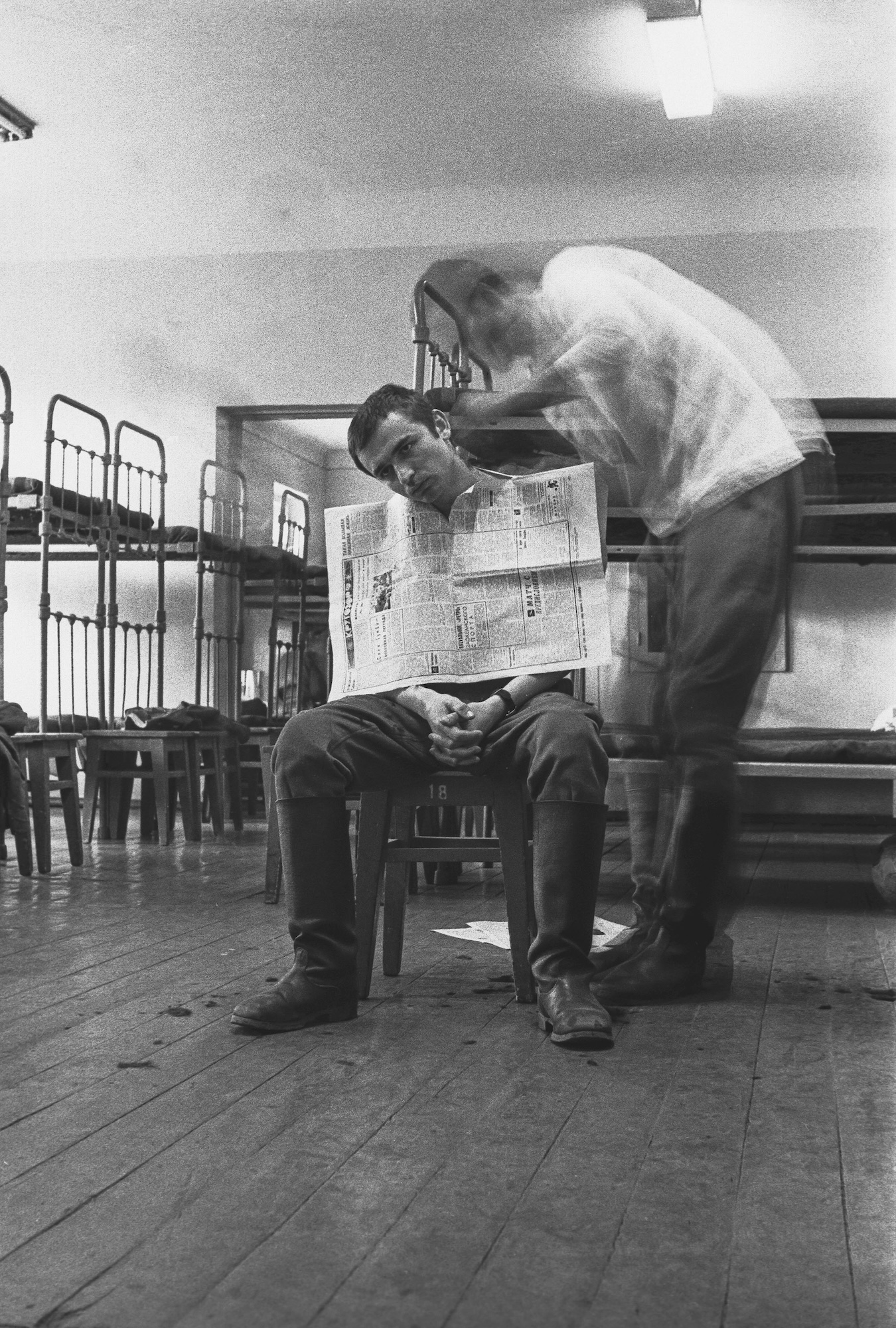

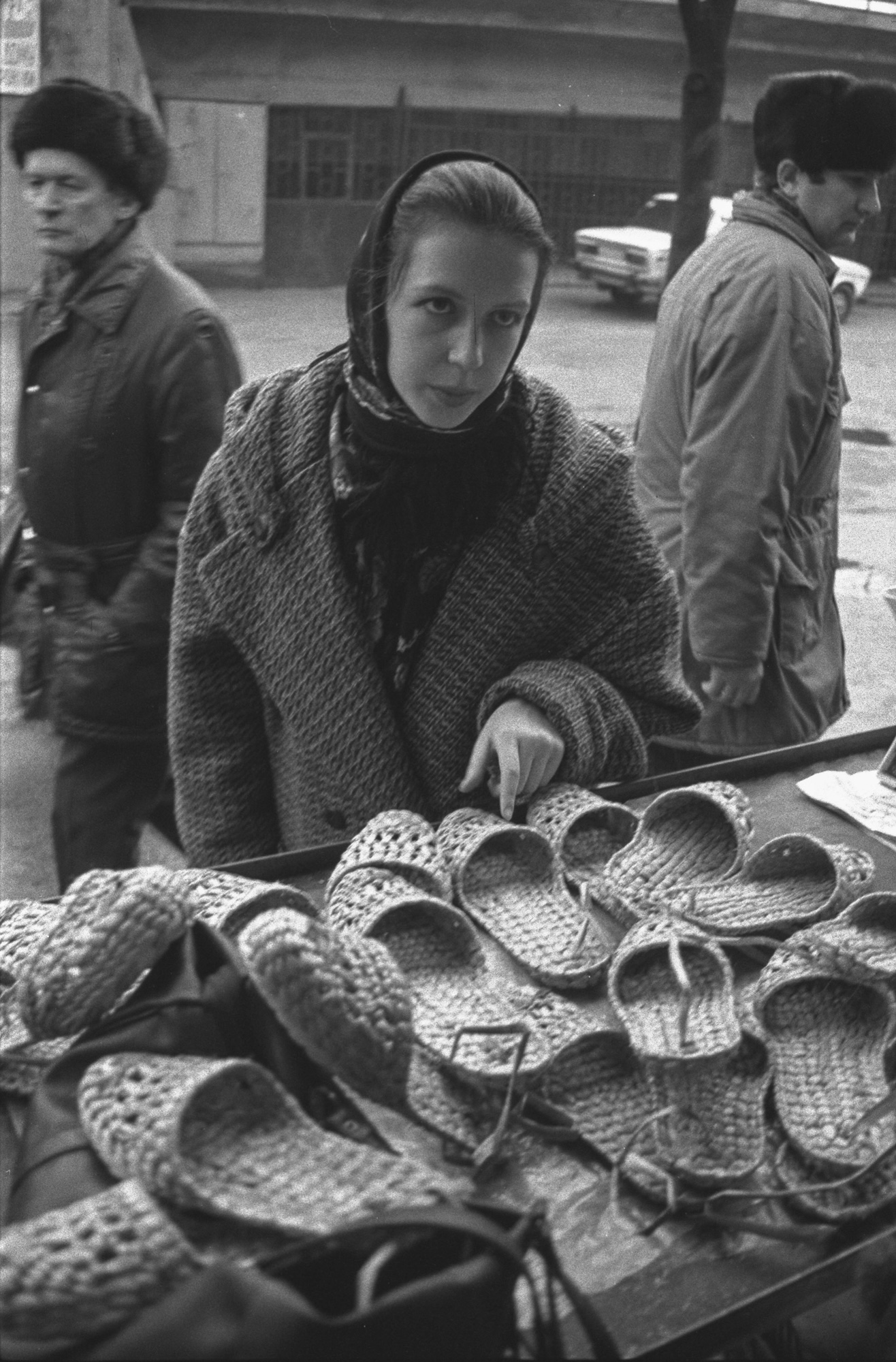

Pavlo Pashchenko is one of the pioneers of new Ukrainian photojournalism in the years leading up to the fall of the Iron Curtain. Since 1986, he photographed for leading Ukrainian newspapers and magazines, and from 1989 also for Western media. His work offers a sharp eye on Ukraine — both in its everyday life and in its defining moments.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Liubov Kukharenko