After World War II, a fairly distinct and persistent habit took hold, spreading across much of Europe and, in our times, reaching even broader geographic areas. This concerns the narrative in which Nazism was utterly defeated, and the idea took root in many intellectual circles that this victory was not so much due to the Allied coalition, but rather to Soviet Marxism, which supposedly single-handedly toppled the treacherous enemy of humanity. It’s worth noting that not all, but a significant number of Western intellectuals are still captivated by such ideas. Meanwhile, the blatant crimes of the communist regime were seen, and still are by some, as a harsh but necessary price for this noble cause. After all, as was often noted in nearly every report on the planned economy, these were merely “additional production costs”. For these reasons, it is interesting to trace how such beliefs were formed, especially when reading the recently translated book Past imperfect: French intellectuals, 1944–1956 by British-American historian Tony Judt.

It is telling that with the Nazi occupation of France, the country established a servile local Vichy government, which ultimately significantly undermined the legitimacy of the right-wing’s claims to shape intellectual life. So it’s no surprise that after the liberation, French intellectuals had no desire to entertain any anti-Marxist arguments, such as those made by Raymond Aron. Thus, when Khrushchev attempted to expose the personality cult that led to mass repression, relocations, purges, famines, and other atrocities, it struck them like a bolt from the blue. At the same time, it’s important to understand that, before the war, French intellectuals mostly avoided politics. It was likely the Resistance movement that forced them to engage and radicalize.

However, no matter how much the sympathizers of communism clung to the brand of Soviet victory, they could not pretend that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact never existed. The situation overall was reminiscent of when the collective dominated over the individual. In metaphorical terms, it was as if from this lofty perspective, no log was deemed suitable for the grand construction project unless its knots had first been planed smooth.

In this vision, evil seemed like a minor deviation from all-conquering good.

In fact, few intellectuals would have dared to deny the demand for the liberation of humanity, even if that required fanning the flames of a global conflagration.

Perhaps the Resistance truly was a force for change, but by 1951, Albert Camus felt that any mention of it evoked little more than a smile. By that time, existentialism had firmly established itself as the intellectual fashion of the day. Rejecting the tradition of academic rationalism and neo-Kantianism, its advocates turned to interpretations of Hegel’s philosophy by a Russian émigré who supported Stalinism—Alexandre Kojève. This was especially true regarding the philosophy of the master-slave dialectic. According to this theory, the self-recognition of the oppressed required the neutralization of the oppressor. Hence, history could not avoid the terror of totality, as the positions of master and slave would constantly switch places. This philosophy explained not only the emergence of Nazism but also the possible “excesses” of Stalinism.

Initially, Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialism lacked any clear political undertones, and questions of morality were almost never raised—unless one considered the problem of the Other. In other words, his philosophy of freedom remained morally neutral. But the war changed everything. Sartre’s partner, Simone de Beauvoir, began to suggest that the situation of choice could suppress respect for anyone’s life.

The argument went like this: since one has to make choices anyway, it’s better to accept that the very act of choosing places a person beyond morality, because no one ever knows the right course of action.

In the postwar reality, her belief was that all collaborators deserved the death penalty without any doubt. However, not everyone shared this view—Camus, for example, strongly disagreed. Nevertheless, Sartre and de Beauvoir argued that true being—authentic existence—always entails protest, especially in the fight to free everyone from the yoke of injustice. Their version of existentialism thus resembled a doctrine allied with Marxism, as both theories identified a common enemy.

Given that existentialism lacks Hegelian or Marxist faith in the inevitability of historical processes, such a stance seemed quite cynical. This is what angered Camus: if you don’t believe in the inevitability of history, then why justify violence? Strangely enough, the reasoning of French intellectuals often led them astray. It’s worth recalling that, during this time, even Maurice Merleau-Ponty, although temporarily, defended violence for the sake of progress. But didn’t this align with the early fascist attempts to practice coercive therapy? However, common counter arguments to this critique often boiled down to the idea that all regimes without exception engaged in violence. Something similar was seen among thinkers connected to Catholicism. Inspired by the ideas of Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev, personalist Emmanuel Mounier sought to renew Christianity on the foundations of Marxism and existentialism. His hope for the emergence of a non-totalitarian community, where the individual would escape capitalist deformation, was overshadowed by his temptation to rely on the Vichy regime.

It’s well known that since the 1930s, news about Soviet labor camps, terror, and similar crimes regularly reached France. Yet some intellectuals managed to justify this as growing pains.

Fascism, apparently, was an act of arbitrariness, while communism, though not without its issues, was intentionally leading toward justice. But there were those who renounced their former loyalties. For example, the founder of surrealism, André Breton, condemned this double-dealing, and Mounier called it a political disgrace. Yet despite everything, repression steadily advanced westward until it reached Eastern and Central Europe. With Moscow’s support, communist regimes in countries like Bulgaria, Poland, Albania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and others began purging both communist and non-communist dissent, including some from within the church. What mattered most was that the accused confessed to their crimes, as this gave the executioners a “moral” advantage. The Western left then adopted the convenient label of “bourgeois nationalism”, and now learned to stigmatize such deviations disregarding any modifier.

While Camus saw these acts as a system revealing itself, Sartre tried to balance both sides—he didn’t endorse the camps but didn’t concern himself with their existence either. Actually, Sartre insisted that the declared goal of liberating and bringing happiness to humanity provided significant leeway. In other words, if the West were truly righteous and offered something more meaningful, it would be justified to condemn Soviet barbarism. But as Camus lamented, a responsible approach to history often frees one from responsibility to actual people. Thus, various reactions emerged: critics of Stalinism were ignored (Raymond Aron); supporters of terror became accomplices (Louis Aragon); steadfast, yet dissenting party members limited their resistance to private acts (Edgar Morin); and those who neither joined the party nor distanced themselves from it were left to maneuver around it (Mounier).

The most common way of whitewashing the issue boiled down to the assertion that the communists oppressed their Self, unlike the Nazis, who targeted the Other.

This was widely accepted among intellectuals, although few acknowledged that “Their Self” had become “the Other”—in other words, an enemy. Some still believed that Soviet power continued the revolution of 1917. Only François Mauriac seemed to realize that this was, in fact, the power of the earlier empire, considering Soviet aggression in Hungary in 1956 as imperial self-preservation. It’s worth noting that the empire was only temporarily communist. This left Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir with a dilemma: condemning Russia would risk undermining Marxism. As a result, Sartre turned a blind eye to its imperial ambitions, and de Beauvoir saw more reason than malice in the actions of Soviet soldiers. It appeared, then, that while capitalism offered no hope, communism still promised much. The fact that communism had taken root in the most backward part of the world gave it considerable credibility.

But what conclusions can we draw from Judt’s analysis? Today, we see Russia inheriting the image of a missionary state. Countries in the so-called Global South still associate it with Marxism. However, aside from its imperialist bravado, Russia now lacks revolutionary zeal. Even during the Soviet era, Western intellectuals like Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein, who initially sought to align their lives with the country, needed only to visit to realize that the perception and reality were fundamentally different. That’s why today, if a Western intellectual sees Russia as a force capable of challenging the flaws of liberal democracy, they prefer to support it from a distance, without ever considering moving there.

There’s something even more striking. In recent decades an idea appeared about closing of the modernization project—as if after independence nationalist tendencies started to intensify. Since Russia’s invasion, similar narratives have been heard from outside Ukraine as well.

What’s most surprising is the belief that without the grandeur of the Russian Empire, Ukrainians are doomed to a backward tribalism, incapable of achieving industrial or technological transformation.

Yet, the accusation of nationalism feels more like the fears of someone afraid of losing their own Russian imperial identity—an identity focused on crushing all differences. This imperial identity blocks the formation of any national identity, even its own, while instead cultivating an ideology of total domination over any individuality. In such a system, any form of distinctiveness can only exist either as subordinate or as marginal. Therefore, remaining within this deceptive totality is like continuing to wear blinders.

Taras Lyuty, philosopher, writer.

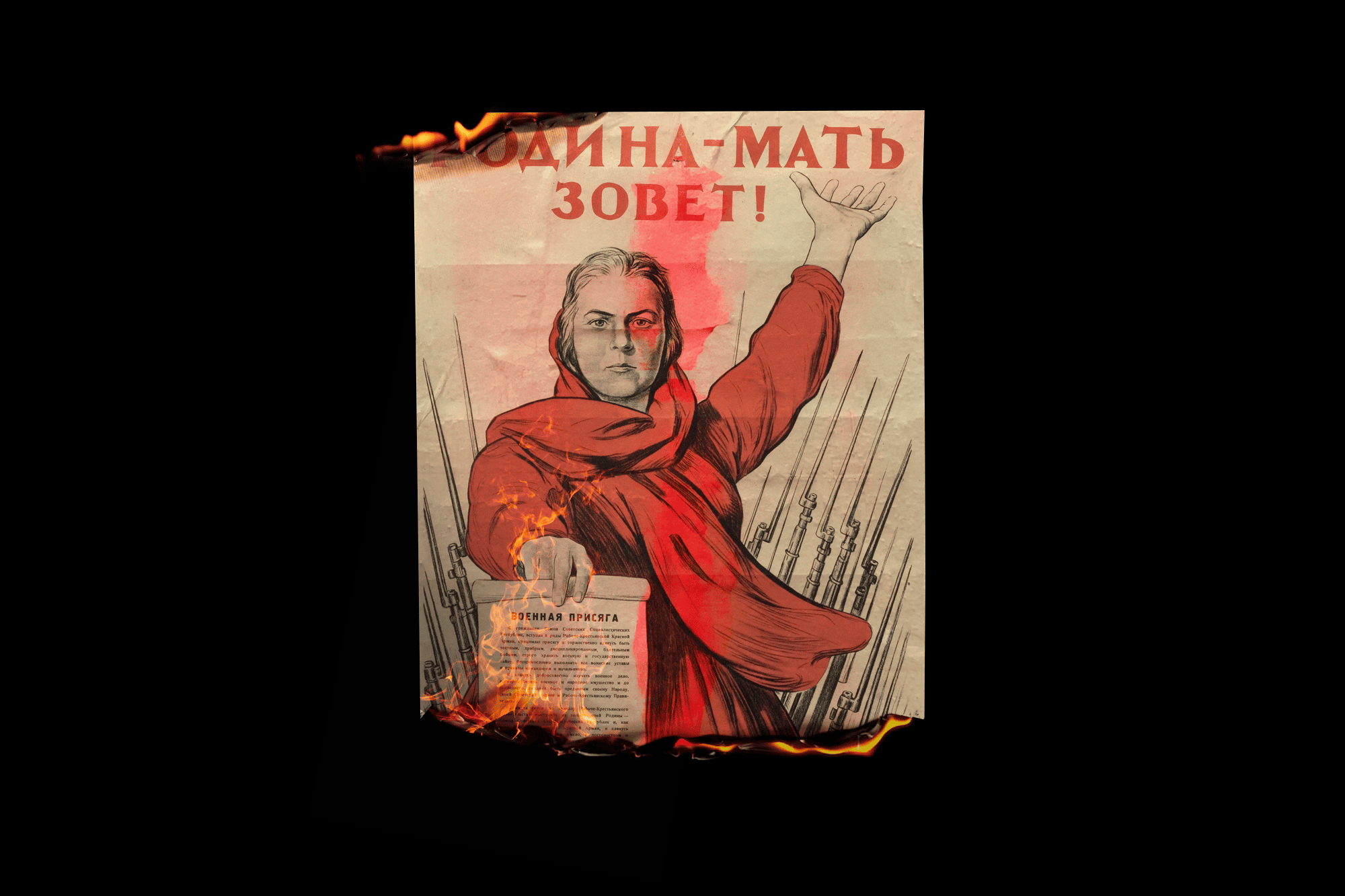

Illustration — Vadym Blonskyi

Translation — Iryna Chalapchii

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]