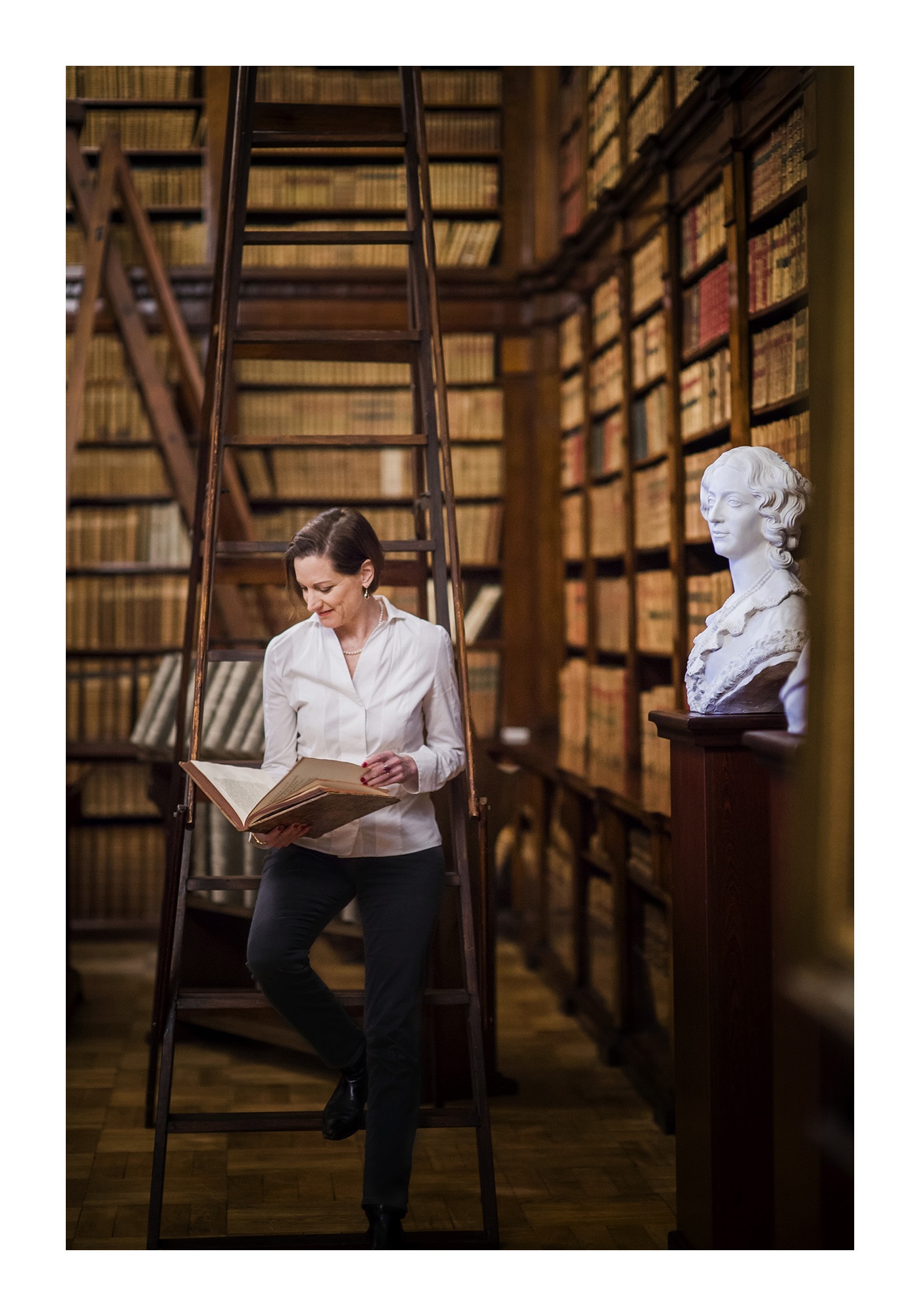

An American historian, writer, and journalist best known for her books “Gulag: A History,” “The Iron Curtain” and “Red Famine. Stalin’s War on Ukraine.” In her latest book, “Autocracy Inc.,” she writes about the fragility of democracy and the authoritarian regimes that want to rule the world. She previously worked for The Economist, The Washington Post and other media outlets — in 2019, she joined The Atlantic team. Since the full-scale invasion, she has written dozens of articles about Ukraine, a country she is not afraid to visit: “I am a journalist, after all,” she explains. “Nowhere is completely safe, so when I’m in Lviv, I feel calm. Maybe I’ve just stopped worrying about it.” In recent years, she has visited not only Lviv and Kyiv, but also Bucha, Borodianka, Kherson, Odesa, Vinnytsia and other cities.

Anne first visited Lviv in 1985. She was traveling by train from Leningrad to Budapest and had six hours to explore the city. Later, in 1990, she came to Lviv to visit friends. What stuck out to her about that trip was that running water was available on a schedule. But now, she says, Lviv has completely changed: “Although the war is still ongoing and there are no funds available for all the necessary restoration, it is clear that the city is developing.” This year, she was brought here by the Lviv Media Forum, where Anne was one of the main speakers. Anne rarely gives interviews — she says she’s laid everything out in her books and articles. So we will consider this conversation, where we discuss the distortion of history, persisting imperial ideas and Ukraine in 10 years, a privilege.

§§

This interview was made possible thanks to LMF 2025 — one of the largest media conferences in Central and Eastern Europe.

§§§

One of your first books is “Gulag: A History,” in which you lay out the facts about political repression in the Soviet Union and the deaths of millions of people in Soviet concentration camps. While Germany underwent a process of denazification after World War II, Russia did not undergo a process of decommunization. The crimes of the Soviet Union were long silenced, and now we see ideas from the past coming back to life. In the occupied territories of Ukraine, Russians are erecting new monuments to Stalin. Why, in your opinion, did the Soviet Union, and later Russia, not acknowledge its guilt for the crimes it has committed?

I have written extensively about this. It is important to remember that there have been Russians who wanted the state to acknowledge Stalin’s crimes. To a certain extent, this process had started to happen. Small memorials would appear throughout the country. There were many historical projects dedicated to remembering and honoring history. And frankly, the best historians of Stalinism were Russian. For example, the Memorial Society wrote the best books; they gathered all the information. A significant part of my book about the Gulag was made possible precisely because of the work of Russian researchers. So we can’t say that Russians weren’t interested.

It should also be noted that in the 1990s, the archives were open. It was possible to conduct research in Russia. I myself worked in the Russian archives in the 1990s. I spent a lot of time there, and I wasn’t the only one — others did too. Not long ago, I ran into a Lithuanian researcher whom I had met in Moscow sometime in the 1990s. At that time, he was working on books about his country. So it was a time of openness, a time of discussion. But then it all stopped. Putin shut everything down — for several reasons.

Firstly, as I already mentioned, Putin believed that discussing history somehow undermined Russia’s statehood. This was especially true because he himself was a KGB officer and understood that such a discussion would undermine the KGB’s authority and strip it of its glorious aura. So this was personal for Putin, but it also concerned Russia as a whole.

There was something else: against the backdrop of the economic crisis of the 1990s, many Russians felt that these discussions about the past, which had been ongoing both then and a decade earlier, did not yield any results or lead to anything positive. Society lost its enthusiasm for the pursuit of the truth, and Russians felt that this may have been what had caused the economic crisis. So, both at the state level and in public opinion, there was a desire to put an end to these discussions.

And that is tragic. First, it meant that Russian history would remain forever distorted in the minds of many Russians. But also, as you pointed out, it became one of the conditions for the return not only of monuments, but also of Stalin-era policies. If you look at my book about the Sovietization of Eastern Europe after World War II, about Soviet policies in Poland, Hungary and Germany, it becomes clear that what happened there then is now happening in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine.

Bulgarian political scientist Ivan Krastev argues that the fall of the Berlin Wall was the starting point for everything you did in the following decades. “For Eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War was not a geopolitical but a moral story, a verdict handed down by history itself.” In your book “The Iron Curtain,” you write about how communism took over Eastern Europe after World War II and how horrendously it changed the people who fell under its control. Now we see that people in East Germany are strongly supportive of AfD. In your opinion, how noticeable is this transformation into “homo sovieticus” — the Soviet person — now, after 30 years of freedom?

The attempt to turn people into model citizens essentially failed.

As you know, the state in the Soviet Union, as well as in occupied Eastern Europe, tried to control culture, education, sports, the media, and, of course, politics and the economy. The goal was to turn everyone into submissive citizens who would never have “wrong” opinions. And this attempt failed. Nowhere — not even in Russia — did they manage to force everyone to think alike, agree that the system was wonderful and become model citizens.

But the truth is that this attempt, this pressure caused people to become wary of the state. They felt distrust, isolated themselves in their own homes and found it increasingly difficult to establish social connections. In other words, it divided people and made them afraid of each other. And, in my opinion, some of this fear, and especially skepticism towards the state, lingers to this day.

Due to propaganda, the Russian population seems to be living in a different reality. They refuse to accept the truth, perceive everyone as enemies and have taken on a defensive stance. This is somewhat reminiscent of Hitler’s propaganda style, when in a country ravaged by destruction and poverty, a new leader gave hope for a “new life” and “restoring greatness.” Why, in your opinion, did this idea of hegemony become possible in the 21st century? After all, we have long been talking about the “end of history” where democracy prevailed.

Imperialist ideas never fully went away. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, many assumed that the triumph of liberal ideas would be decisive and lasting. But if you look at human history, everything happens cyclically. Liberal democracies are very difficult to maintain – they require a certain consensus. And when that consensus is broken, it is very difficult to restore. Therefore, in my opinion, it is not surprising that these ideas have returned, because, in fact, they never disappeared. And we cannot claim that they ever ceased to exist.

In your new book, “Autocracy, Inc.: The Dictators Who Want to Run the World,” you write about governments that, despite not sharing a common ideology, cooperate to increase their power and control against democratic and liberal countries. Chinese and Russian nationalism, Venezuelan socialism, North Korean “Juche,” Islamic State radicalism. Unfortunately, with Trump’s rise to power, America can now also be included on this list. How do you assess the steps taken by Trump and other MAGA representatives in their first months in power?

America is not a dictatorship. There is still political opposition in America. There is a free media, there is a Constitution, and there is freedom of speech. So I wouldn’t exaggerate the similarities between the United States and Russia. I don’t think we’re there yet. It’s true that Donald Trump, as a person, admires authoritarian leaders, and it’s true that he — and this is the most important thing to know about him — doesn’t understand the limits of his power. He sees no reason why he should not, for example, use the presidency to enrich himself, or why there should be any restrictions or institutions of oversight. Why should Congress, the courts or anyone else have the right to question his actions? And that is very un-American, very far from the American tradition.

I think it’s too early to say where this will lead. Trump is already facing legal challenges. And ultimately, Congress — in accordance with the principles of how our system is supposed to work — may also decide to rein him in. This hasn’t happened yet, but it may well happen. So yes, although Trump admires autocrats and tries to emulate them, we do not yet know how the system will try to restrain him. Only a few months have passed [this interview was recorded during LMF, on May 15–17, 2025. — Ed.].

So you still have some hope?

Yes, this story is only just beginning.

I would like to discuss the influence of the New Apostolic Church on American society. I remember Stephanie McCrummen’s article in The Atlantic, “The Army of God Come Out of the Shadows,” which talks about this organization’s intention to destroy the secular state. To what extent, in your opinion, is the New Apostolic Church connected with ideas of undermining the pillars of democracy?

There have always been evangelical Christians in the United States who do not accept the secular state — they have existed here for decades, perhaps even centuries. They’ve never had political power at the federal level before, although they sometimes had influence at the state level. In other words, they did hold power at one point or another.

One of the reasons they supported Donald Trump, even though he is not a Christian, was that he seemed radical enough to be able to destroy the existing state — and then, in their view, they could fill that void. They do not represent the majority of Americans, and I am not even sure they represent the majority of Christians. But yes, they exist, though I cannot give you specific figures. I don’t even know how important they are as an electoral bloc. Yes, they are written about, and yes, they are a real force, but whether there are more of them than before or fewer, I simply do not know.

What is your opinion on Trump’s policy change vis-à-vis Ukraine?

When we’re trying to find the right words to say something in general about Donald Trump, we need to understand that he doesn’t really have a strategy. He doesn’t adhere to any political theory. He doesn’t have a vision of how the war will end. His idea was that when he became president, everything would change because of him, and that Putin would agree with him, and that if he was just nice to Putin, Putin would stop the war. I think he really believed that. And although it sounds very naїve, I think that’s an accurate description of his approach.

Now we are at a point when it became obvious that this won’t happen. Everything will not work out the way he imagined. And now Trump needs a new strategy. What exactly that strategy will be, I do not know. He tried to pressure Ukraine, yell at Zelensky, hoping that this would win Putin’s favor. That did not work.

Some people around him, including members of Congress and the Senate, now want him to start putting pressure on Russia. Maybe he will do that, I don’t know. He wants the war to end — I think that’s true, mainly because he made this promise, and he knows that he hasn’t kept it.

But Trump doesn’t understand the war itself. He doesn’t know why it started. He doesn’t understand what it will take to end it. And he has no idea what Russia’s goals are or why it’s pursuing this war.

So he has no concept of how to end this war. And now he’s just looking around for new ideas. Honestly, I don’t know what he’ll do.

While we are here at the Lviv Media Forum, negotiations involving Russia, Ukraine and the United States are taking place in Istanbul. To what extent do you think the claim that peace will come soon is realistic?

I want to emphasize that I don’t have any insider knowledge about this. But judging by everything that has been said publicly — by Putin, Lavrov, Russian propagandists on television — I don’t see any interest on Russia’s part in ending the war. I haven’t heard them say that they want to end it. I have not heard them talk seriously about a ceasefire. I have not heard them recognize Ukraine’s right to exist as a sovereign state.

So, as of now, I see no signs of the war ending. But perhaps there are things happening that are invisible to me, that I do not know about.

Today, Europe is essentially losing the protection and support of the U.S. and must find the strength to protect itself. How prepared do you think Europe is for this prospect?

I think Europeans are more prepared now than they were before. There are many things that people say privately but do not voice publicly. It seems to me that almost everyone in Europe actually understands that the United States has changed significantly and that a completely different policy is required. And that there may come a time when the U.S. is no longer a part of NATO or when American troops withdraw from Europe. Everyone understands this. Of course, no one wants to talk about it openly, because no one wants to push the U.S. to leave or encourage them to do so.

There are things that Europe will have to do, but this will take time, especially in the field of intelligence and satellites. Europe does not yet have its own satellite intelligence, although certain structures are currently being created. But we do not have a direct equivalent to the American satellite intelligence. And this is not something that can be fixed in a month — it will take time.

Another problem facing Europe — and not only Europe — is the insufficient supply of air defense systems. I am referring to Patriot batteries and ammunition for them. They are being used by the Israelis, too. And for technical reasons, it is simply impossible to manufacture them quickly in sufficient quantities. So there are certain gaps in what can be done right now.

That is why you will not hear any European government or politician say that they are severing ties with the United States or distancing themselves from it. In addition, some still hope that this is only the beginning of the presidential term, that Trump may change, or that there will be a different president next term. So no one wants to do anything that could permanently destroy relations.

I think everyone realizes that things can change dramatically and have started preparing for this. Every European government has a part of its Ministry of Defense that is dedicated to planning for a future without the U.S.. Yes, people are thinking about it, making plans and starting to rebuild their armies with this in mind. But you won’t hear any public rifts. And, in my opinion, that’s perfectly understandable.

Democratic and liberal countries are currently facing an enormous challenge. It used to be believed that the democratic system was given to us for free — that is how we perceived it over the past decades. In your opinion, what is the price of democracy today?

People took democracy for granted. This is especially true of people my age and younger — those who grew up in democratic countries, never fought for democracy, and simply assumed that it would always be there.

They viewed it a bit like running water: you open the tap, and it’s there. Do you know where it came from? No. Do you care how it got into your bathroom? No. Democracy was perceived in the same way: it’s there, we vote once every four years, and we don’t think too much about it.

But the lesson of the last few years is that from time to time, democracy has to be fought for or at least worked for, in order to preserve it. Democracy does not really work without a certain level of civic engagement. That is, there must be people who are willing to run for office, work for candidates, help the system function, devote time to understanding political challenges and make their voices heard. All of this requires additional time commitments beyond the job that the person already has. You are a doctor, a lawyer or a construction worker and you have one more “job” — being a citizen. This takes up time. And many people have stopped doing it.

And yes, you are right. Recent years have taught us that we really need to treat democracy like water from a well. Sometimes, you have to go to the well, draw water, bring it home and use it. We need to learn how to do this again. In other words, the ability to ensure the functioning of the system is now an integral part of citizenship.

But I hear about this in many countries. In the U.S., there is a lot of talk right now about what ordinary people can do to change the system. And I see that the level of engagement is growing, compared to what it was before. I’ve heard that the same thing is happening in Poland and the U.K. as well. So yes, the level of awareness of the fragility of democracy and how much effort it takes to preserve it has become much higher.

As we know, Ukrainians are fighting to defend democratic values and, in fact, our independence, by fighting on the front lines. Do you think the “Western world” should also defend these democratic values by military means?

If necessary, yes. If Estonia is invaded, Estonians will fight. If Poland is invaded, Poles will also fight. It is quite possible that, depending on the course of the war, we will see greater mobilization in Europe in support of Ukraine.

Amidst clashes between empires, we, Ukrainians, have our own vision of the future and the country we all dream of living in. How would you define the Ukrainian dream?

I don’t feel I have the right to say what the Ukrainian dream should be. I believe that it is Ukrainians themselves who must build this dream. If I say what I think, it would seem as if I’m imposing my opinion.

What do you imagine Ukraine will be like in, say, 10 years?

I can easily imagine Ukraine in 10 years as part of Europe — prosperous, rebuilt not quickly and carelessly, but carefully and with a creative approach. I have met so many creative Ukrainians with ideas… Once, I spent a day with an architect who wanted to rebuild destroyed villages based on traditional architecture. I know that Ukraine is very creative and far ahead of the rest of the world in the use of drones, technology and its own software to block the Russians in cyberspace. All of this will ultimately benefit Ukraine. When the war ends — one way or another — you will have one of the most technologically advanced armies in the world. You will have the most powerful drone industry, one of the best military-tech industries. People from all over the world will come here to learn, and you will earn money from this and prosper. This is one of my predictions.

But that’s not all. All the things that seem painful now — all this resilience, the organization of civil society in support of the military, projects that help abducted children — all this will bear fruit. These initiatives have brought people together, created new organizations and new institutions. The people who led them will become the next leaders of Ukraine, because they are trusted and have social capital. I am even more confident about Ukraine’s future leadership in 20 years than I am about the same generation in Western European countries. These are creative people who have learned to do a lot with limited resources and to work together in very difficult conditions. Ukraine has enormous potential, and everyone understands this.

Photos: Provided by Anne Applebaum.

Translation from the Ukrainian by Liubov Kukharenko