It’s only now that I look back with astonishment at the chaotic and senseless world I was growing up in. I am amazed as I recall the bizarre values held by the people around me—acquaintances, friends, close relatives, distant relatives. It’s now glaringly clear where the mishmash in my head came from—the same one that shaped my social identity.

At the time, everything seemed logical; everything worked consistently and coexisted in harmony.

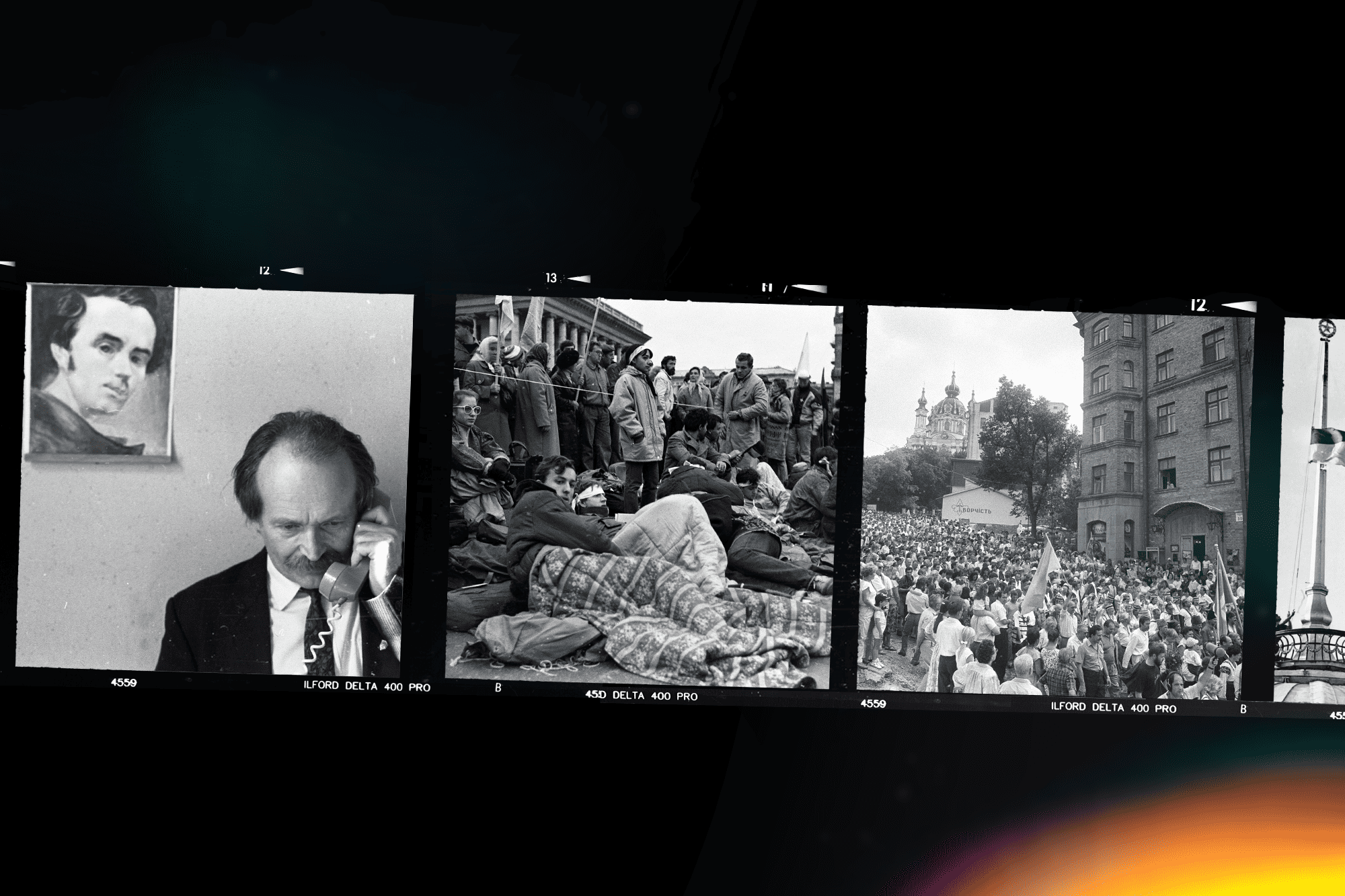

It was 1991. I was six years old. And this age of mine—when a child learns, absorbs truths and sets a moral compass—fell precisely at a time when the world around me had no clear truths, no moral foundations to lean on with skinned knees, and no logical connections between the past and the future.

My father had a green car, a Soviet-era Zhiguli, and he would drive my mother and me to our dacha, a recently acquired plot of land with an old house forty kilometers from Cherkasy. He also made new friends who drove German cars, wore denim jackets, and smoked imported cigarettes. To me, they were like wizards from another world, so different that they could effortlessly pull out a Hershey’s chocolate bar or a packet of Skittles from their pockets.

Around the same time, my mother had just begun studying philology at an institute, where she gained access to literature she had never encountered before: books that revealed Soviet crimes, imperial court intrigues, and the secrets of Russian eros. Eager to share her newfound knowledge, and as I have always been nearby, she would turn to me as her audience. She vividly described Stalinist-era camp life, talked about royal dynasties, took me to see the bleak Soviet films of the late perestroika period, and quoted the Symbolists, especially Brusov.

That same summer, my paternal grandfather gave me a Young Pioneer yellow badge, telling me I would soon wear it rightly. I longed for that initiation; it felt like being inducted into a secret knightly order. But my grandfather also manipulated me, reminding me that real Young Pioneers exercised, washed dishes, and scratched their grandfathers’ backs.

Meanwhile, I was surrounded by the magazine Murzilka magazine, a Soviet primar book, Ninja Turtles and Hollywood B-movies. The echoes of the Afghan war and the paranoia of radiation sickness only heightened the sense of carnival chaos.

Back then, Hershey’s chocolates, the Gulag, and Lenin’s image inside a five-pointed star coexisted in perfect harmony in my head.

It was an interesting world to explore, colorful and diverse, and it all seemed to fit neatly on one shelf. Only now do I realize what kind of mental porridge I was fed, the damp and moldy fodder I grew up on. Everything moved at the speed of a Porsche 917, barely under control, much like Steve McQueen’s character in Le Mans. It’s no wonder that no one informed me about Ukraine’s independence. It wasn’t hidden from me, but it wasn’t deemed necessary to tell a six-year-old boy, caught in the whirlwind, that he now lived in a country he had never even heard of. Moreover, I would never wear that Young Pioneer yellow badge.

My memory suddenly brings back an image: my mother, upon seeing the badge on my chest, ordered me to take it off, plunging me once again into the murky waters of historical discourse. Yet, she didn’t say a word about the new reality or the new country we were living in.

Life went on as before, though within the borders of a new state. Not a word about the civilizational mission of an independent Ukraine, no recognition of the historical significance of the collapse of the Soviet Union, in which my family remained mentally stuck, unable to break free neither in a year, nor in two, or even in ten years from the renewed, though ancient country. And, most regrettably, they never declared the concepts of Ukraine’s independence or Ukrainians’ belonging to a certain civilisational (European?) community, which are now clear to every first-grader. We continued subscribing to magazines like Smena, Yunost’, and Family and School, and we read literature both sanctioned and banned by Moscow.

We were still wearing out Gogol’s overcoat, while eyeing Shevchenko’s heavy fur coat with suspicion, fearing it would reek of sweat, onions and bitter tobacco.

Like most children, I adhered to simple ethical concepts of right and wrong. They made life easier. I grew up with the understanding that the Soviet Union was evil, but I never fully grasped that an independent Ukraine was good, and we should cherish our freedom and find our true identity. This left me in a state of catastrophic frustration that undermined my identity: Hershey’s chocolates, the Gulag, tiny Lenin…

Today, I regret that I don’t even vaguely remember those August days. That there was no evening on August 24th, no conversation with an adult who might have explained, however, they could or would like, what had happened and what the future might hold. I wish I could describe to my son what those days were like, what the air smelled like, what I felt, and what the people around me felt. Independence happened without me, and I was never invited to the celebration.

Artem Chekh, writer, junior sergeant of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, volunteered to defend Ukraine in 2015-2016, and has been back in the ranks since the beginning of the full-scale war.

Illustration—Vadym Blonskyi

Translation—Marta Gosovska

Copy Editing—Jared Goyette

This publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework «European Renaissance of Ukraine» project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation.