“…I do remember the day that’s approaching, yet I keep thinking that in the last ten years I have enjoyed more happy days, while you were faced with constant hardships. Well, let us hope that in the next ten years it will be the other way around — I’m ready to redistribute the joys and worries between us.”

On January 27, 1966 — their 10th wedding anniversary — Liolia Svitlychna received this letter from her Ivan. Svitlychnyi had been arrested a few months earlier. On the last day of summer, their apartment at 35 Umanska Street was raided. Ivan wasn’t at home. A week later, Leonida Svitlychna officially inquired with the KGB about her husband’s whereabouts and received an answer: he had been arrested and held in a detention center.

In the next 10 years, their joys and worries did not end up being split evenly. Ivan Svitlychnyi was arrested for the second time and sent back to the camps.

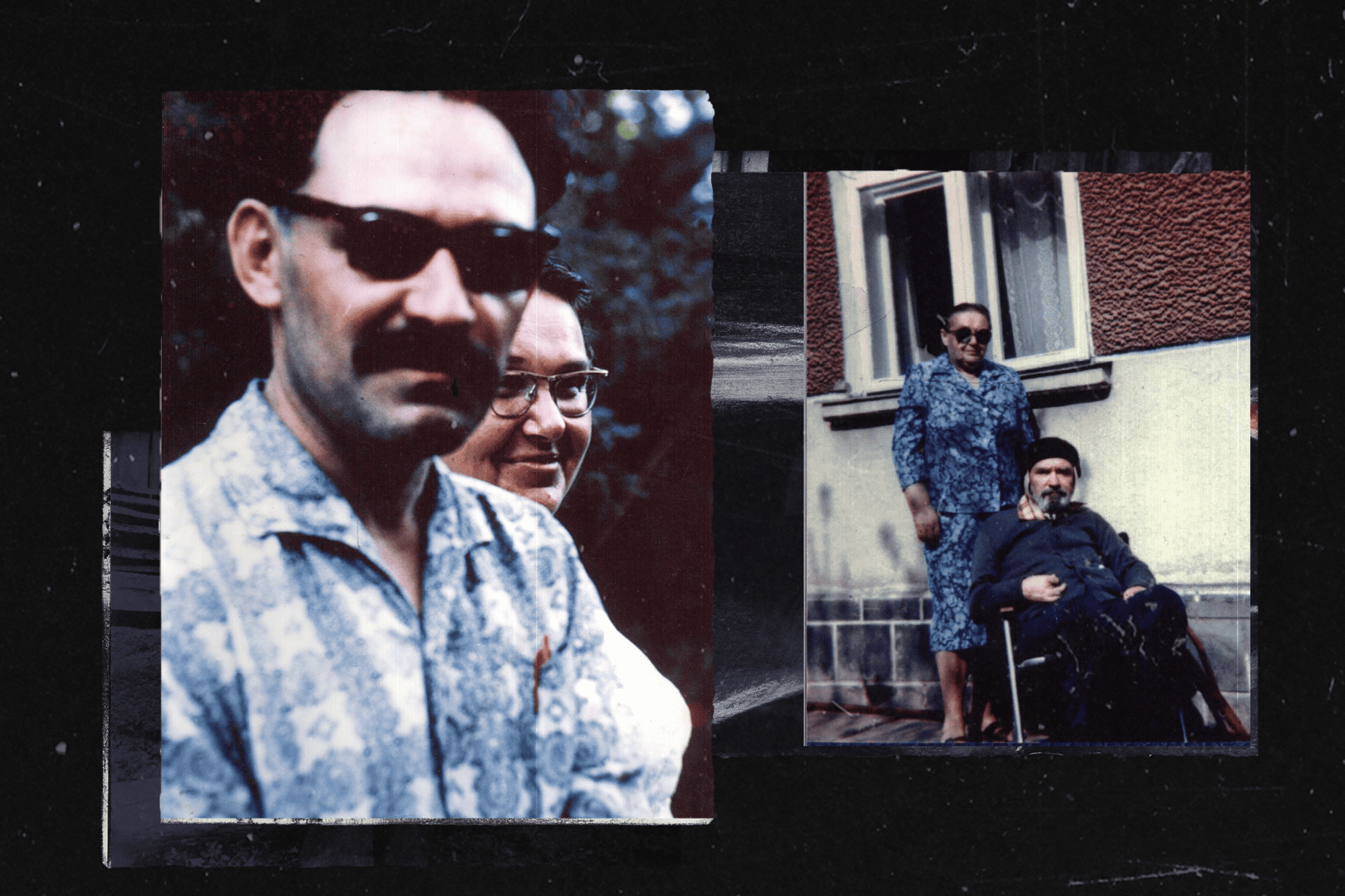

They celebrated their silver wedding anniversary in 1981 together in Altai, where Ivan was in exile.

On their 30th anniversary, following imprisonment, hunger strikes, exile, old and new health issues, there was little cause for celebration.

On their 35th anniversary, Ivan could no longer speak or move and ate out of Liolia’s hands. She was the only one who understood what he was trying to communicate.

In January 1993, they would have celebrated 37 years of marriage, but Ivan died three months earlier.

It is no coincidence that this excerpt from the Gospel of John [Ukrainian: “Gospel of Ivan” — Ed.] is etched on his tombstone: “He was a lamp that burned and gave light.”

It is also no coincidence that after his death, Viacheslav Chornovil wrote: “Today, I have this feeling that we are eternal and immortal. After all, it all happened so long ago. We outlived Stalin! We lived through the [Khrushchev] thaw, and we survived the sixties. We were destined to witness what the Executed Renaissance generation of the 1920s did not live to see. Only a few of them experienced the thaw of the 1960s, and only a handful survived to see our day. We scattered — some entered into politics, some became writers, some joined one party, and others joined another. But we need people who bring us together. Ivan Svitlychnyi brought us, the Sixtiers, together. Let us not forget this.” [Sixtiers, Ukrainian “shistdesiatnyky” refers to the 1960s Ukrainian cultural dissident movement — Ed.]

§§§

[This piece was made possible thanks to the support of The Ukrainians Media community — hundreds of people who believe in independent, high-quality journalism. Join to help us keep creating meaningful content.]

§§§

From the library to the wedding

In the early 1950s, Akademka (the Vernadsky Library) was the best place to study in Kyiv. So many undergrads and graduate students gathered there that every two hours, even in the dead of winter, its large windows would need to be opened to let the fresh air in. That’s when everyone would be kicked out of the reading halls into the hallways, and in those hallways, people met and fell in love.

One day, a newcomer appeared among the graduate students from the Institute of Literature. Leonida Tereshchenko, a longtime Akademka visitor and a graduate student at the Institute of Structural Mechanics, did not pay much attention to him. He looked like any other guy — poorly dressed, high forehead, dark hair combed back. Skinny. He introduced himself as Ivan Svitlychnyi. From time to time, they would cross paths in the library hallways.

“Some time had passed. One day I was listening to a lecture, and when I looked at the blackboard, instead of formulas I saw… Ivan. His face emerged from my subconscious, and continued emerging time and time again,” recalls Leonida in her book “Kind-Eyed: Remembering Ivan Svitlychnyi.”

After spending their days at the library, they hurried to the theaters, cinemas, and concerts in the evenings. He would walk her to the stop of the tram that took her home to Podil. At that time, Svitlychnyi lived in the postgraduate dorm on Kostiolna. Before moving to Kyiv, he graduated with honors from the Department of Ukrainian Philology at Kharkiv University. Liolia graduated from the Construction Institute. It seemed as if they belonged to two different worlds. Yet, a year after they met, they decided to create their own. The wedding got postponed, however, due to the death of the groom’s father.

In January of 1956, Liolia headed to her own wedding in Polovynkyne, Ivan’s native village, along with her odd dowry. He was waiting for her there.

“Ivan’s post-graduate studies had ended, so he needed to move out of the dorm. By that time, he’d accrued many books — as he always did, wherever he was. So I was transporting a very unique “dowry” to Polovynkyne — two sacks of Ivan’s books, which I was barely able to carry into the train,” Liolia recalled.

First, she took the train to Kharkiv. Then, with Ivan’s sister Nadiya, she traveled by train to Svatove, after which they had to travel 60 more kilometers by bus to Starobilsk. Only, due to the snowstorm, all the buses were cancelled.

“The bus station was located in a tiny house, about 15 square meters, but because of delays, a whole bunch of people got stuck in there. We had to wait for three days for the roads to get cleared. We finally got to Polovynkyne, but the groom… wasn’t there. Ivan and his best man Slavko Petyk, his university buddy, couldn’t wait for my bus any longer, so they took the kolkhoz horses and tried to reach us by horse-drawn sleigh. Somehow, we’d missed each other on the way,” wrote Liolia.

In Polovynkyne, the Svitlychnys lived in a clay house with two rooms. The only light source they had was a kerosene lamp. Ivan was the eldest son in a family of illiterate farmers. His mother worked as hired help to feed the family, and, more than anything else, she wanted her children, Ivan, Mariya and Nadiya, to receive an education.

In 1943, their house was taken over by the Germans. The Svitlychnys moved into the barn. Ivan and his friend decided to make explosives and blow up a German weapons depot, but the device exploded in young Ivan’s hands. Only his little fingers remained intact; all other fingers were injured.

Around this time in Kyiv, Leonida Tereshchenko was hiding with her mother from the Germans in the crypts of the Baikove Cemetery. Before that, she deliberately enrolled in the medical and then hydromeliorative institutes — the only ones that functioned during the occupation — because students were not sent to Germany as Ostarbeiters.

For four years, the young couple lived in a room that had once been a monastic cell in the Frolivsky Monastery. Six people lived within a 14-square-meter space: them, Leonida’s mother, and her brother’s family. They slept on books. They left early in the morning and returned late at night. Ivan worked as a junior researcher at the Institute of Literature and later at the Dnipro magazine. Liolia worked at the Construction Institute.

They earned 180 karbovantsi between the two of them, most of which they would spend on books.

“The Dovecote” on Umanska

In 1960, the Svitlychnys finally got an apartment. It was small, but it had a kitchen and all the amenities. It was theirs. It was on the fifth floor. They moved from Frolivska Street to Umanska Street with one suitcase and a truckload of books.

Today, in the courtyard on Umanska Street — a typical Khrushchev-era block — I sit on a bench and stare at the fifth-floor window. I look at it in awe. I imagine a young Vasyl Stus pushing open the entry door. Or Symonenko. It’s likely the doors were different then, that nothing remains of the Svitlychnys in their old apartment, and that the people who live here now are indifferent to the Sixtiers. But if walls could remember, they would remember the voices of the best of the 1960s generation.

The voice of Vasyl Symonenko. The voice of Vasyl Stus. Here they are, reciting their poems. Svitlychnyi presses the button on his tape recorder. And thanks to him, in 2025 I can listen to the Vasyls’ voices.

“The Dovecote.” That’s what Stus called the apartment that became the center of literary and cultural life in the capital. Poets read their poems here. Discussions took place here. Ivan Drach, Lina Kostenko, Ihor Kalynets, Mykola Vinhranovsky, Yevhen Sverstiuk and Ivan Dziuba all came here to spend time together. Liolia served them whatever food she had on hand. Those who needed to stay over for the night or longer. Ivan gave literary advice and books from the best library in Kyiv — his own. “The Mustachioed Aesthete,” as Symonenko called him; or “the Mustachioed Sunbeam,” as Stus called him.

“I bow before my dear Mustachioed Sunbeam, and before my mustacheless hosts, with whom I enjoyed so many warm conversations and silences,” wrote Stus to Svitlychnyi from behind bars. “I remember the book-laden walls, shelves filled with art prints, ceramics, books and the thoughtful twilight hours so befitting contemplation and content. As God is my witness — if I were to recall all the homiest places in Kyiv, that swallow’s nest beneath the very roof was one of them.”

A girl comes out of the Svitlychnys’ apartment building. She’s hopping cheerfully, her dog on a leash. “Are you waiting for someone?” she asks me, a strange woman who’s been standing under the windows of her house for several hours. “The ones I’m waiting for are long gone.” The girl is befuddled: “How come?” “They used to live here on the fifth floor. Maybe you’ve heard of them — the Svitlychnys? Or perhaps you’ve heard of the poet Vasyl Symonenko. His poems are in the school curriculum; he used to visit them.” “Yes, we studied him in school.” The girl walks away with her dog.

There’s no one left living in the house on Umanska Street who would remember the guests visiting that entrance on the corner in the 1960s.

Tricks for the KGB

On August 31, 1965, the Svitlychnys’ home was raided. The entire apartment was turned over. Despite being maimed by explosives as a child, Ivan was quite handy — he was a hairdresser for the women in his immediate circle, repaired watches and appliances and fixed plumbing. He was also quite skilled in deceiving KGB agents.

In the apartment, there was a homemade door in the bookcase that divided the room into two parts. It opened after a certain sequence of steps: first, you had to open the refrigerator, then flip the switch in the hallway…

The lock on the front door also had some secret features. As Ivan’s sister Nadiya Stitlychna later described these inventions, “He honed his ingenuity and didn’t allow anyone to turn him into a guinea pig, though they called him ‘Hare.’” (a school nickname because of his ears).

In 1965, Ivan was arrested on the train. Liolia was summoned for questioning. “Is my husband a murderer, or a rapist? Why did you arrest him?” she asked the detectives, trying to highlight the absurdity of the situation. Lina Kostenko gathered signatures for Svitlychnyi’s release. Ivan Drach wrote an inscription on the criminal code book that Leonida wanted to deliver to Ivan: “May the mustache land back on its airfield…”

During one round of questioning, Ivan asked the KGB agent why so many idiots worked for them, and he replied: “Do you think a smart person would go for a job like this?” On April 2, 1966, he sent a birthday greeting to Liolia:

“Dear Liolia!

Since I have no way of congratulating you in person, and you currently serve as my polpred [the Soviet term for plenipotentiary; until 1941 they were the diplomatic representatives of the USSR to a foreign government – Auth.] and the temporary head of our family, I ask you to proclaim this in my name when the time comes:

Long live Liolia!

Liolia, may you be here for many years!

May you have much happiness

Just as much as hardships! (Which has been plentiful so far)”

On the morning of April 30, Liolia got summoned by the head of the KGB, who informed her that Ivan would be released as he was considered “socially non-threatening.” A few minutes later, he was brought to her. He didn’t know he was getting released — in the morning, he was washing the floors in his cell, as physical exercise. When he went to collect his things, Liolia cried for the first time in the eight months of his imprisonment.

In the evening, the Svitlychnys went to the Pechersk district to Lina Kostenko’s house. They traveled home at night. A stranger came up to them in the underground pedestrian crossing on Besarabska Square:

“Are you Svitlychnyi?”

“Yes…”

“You got released?”

“Evidently…”

In the morning, everyone in Lviv knew that Ivan was free. The stranger, as it happened, was from there.

The second arrest

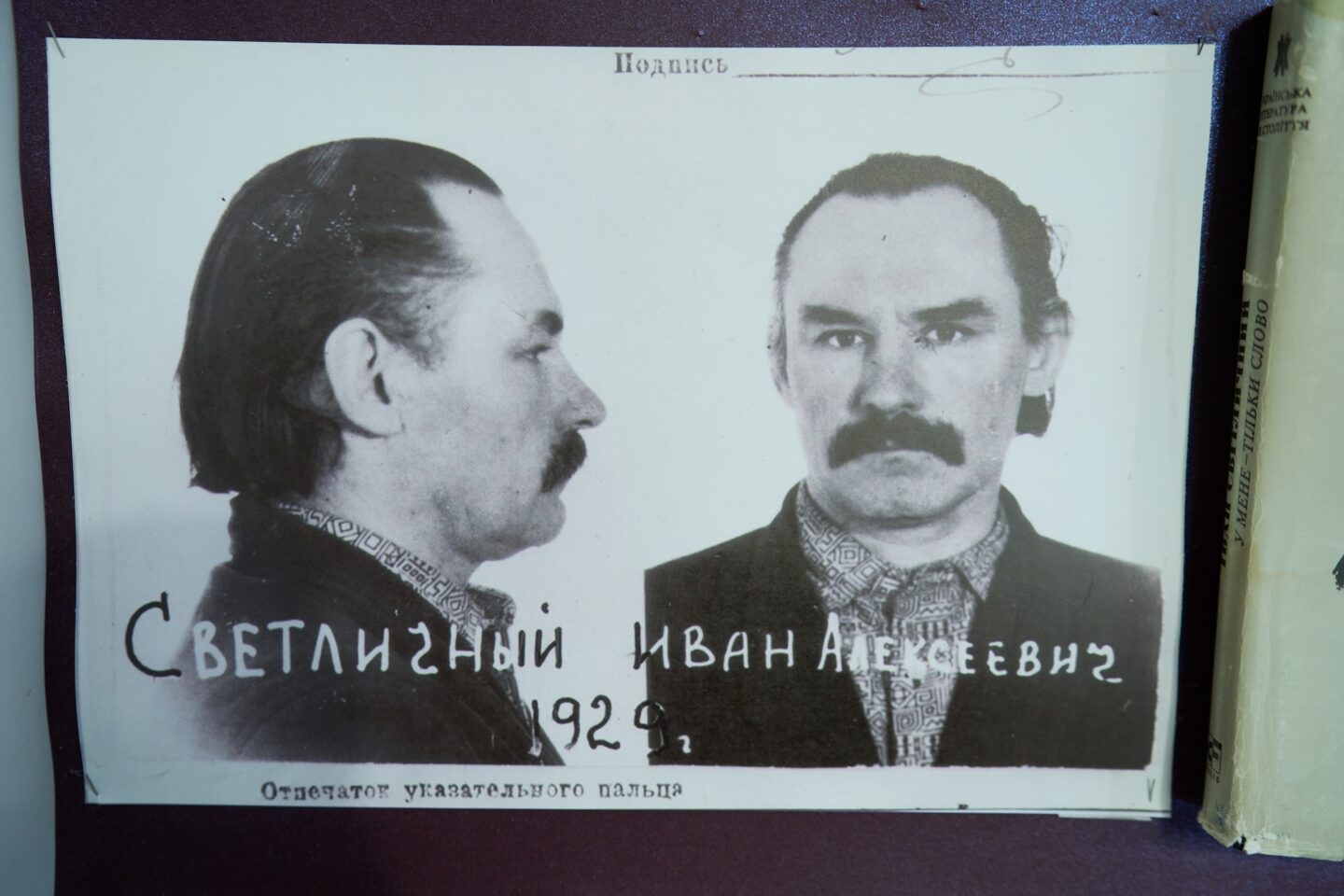

From the moment he was released in 1965, Svitlychnyi was blacklisted. His works were no longer published. He translated and published under pseudonyms. In January 1972, he was arrested for the second time. As before, he was charged under Article 62 of the Criminal Code — anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. That time, Svitlychnyi’s sister Nadiya, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Vasyl Stus and Viacheslav Chornovil were also detained.

Ivan does not lose his sense of humor during the investigation. Detective Siryk told Nadiya Svitlychna a curious story. When he was questioning Ivan, the latter suddenly asked, “How do you feel about striptease?” Siryk, taken aback, mumbled something in response. Ivan continued, “I’ll take off my sweater, then, because it’s quite warm in here.”

A year later, in a closed court session, Svitlychnyi was sentenced to 12 years: seven in a strict corrective colony and five in exile. Ivan’s mother and wife were not allowed to attend the trial.

“I remember how Liolia came up to me after the trial, all dressed up in a black suit with a beautiful brooch, her eyes shining, saying, ‘Full charges!’ It sounds like a story, but it’s true; it really happened, I’m not making it up. She was so joyous — they sentenced her husband to 12 years, but she was radiant,” recalled Mykhailyna Kotsyubynska.

To outsiders, it seemed strange — the wife was happy that her husband had been given the harshest sentence. But Leonida was worried that he would crack under pressure and that it would kill him faster than any “full charges.” He didn’t crack. And that’s why she was happy.

Letters and messages on buttered bread

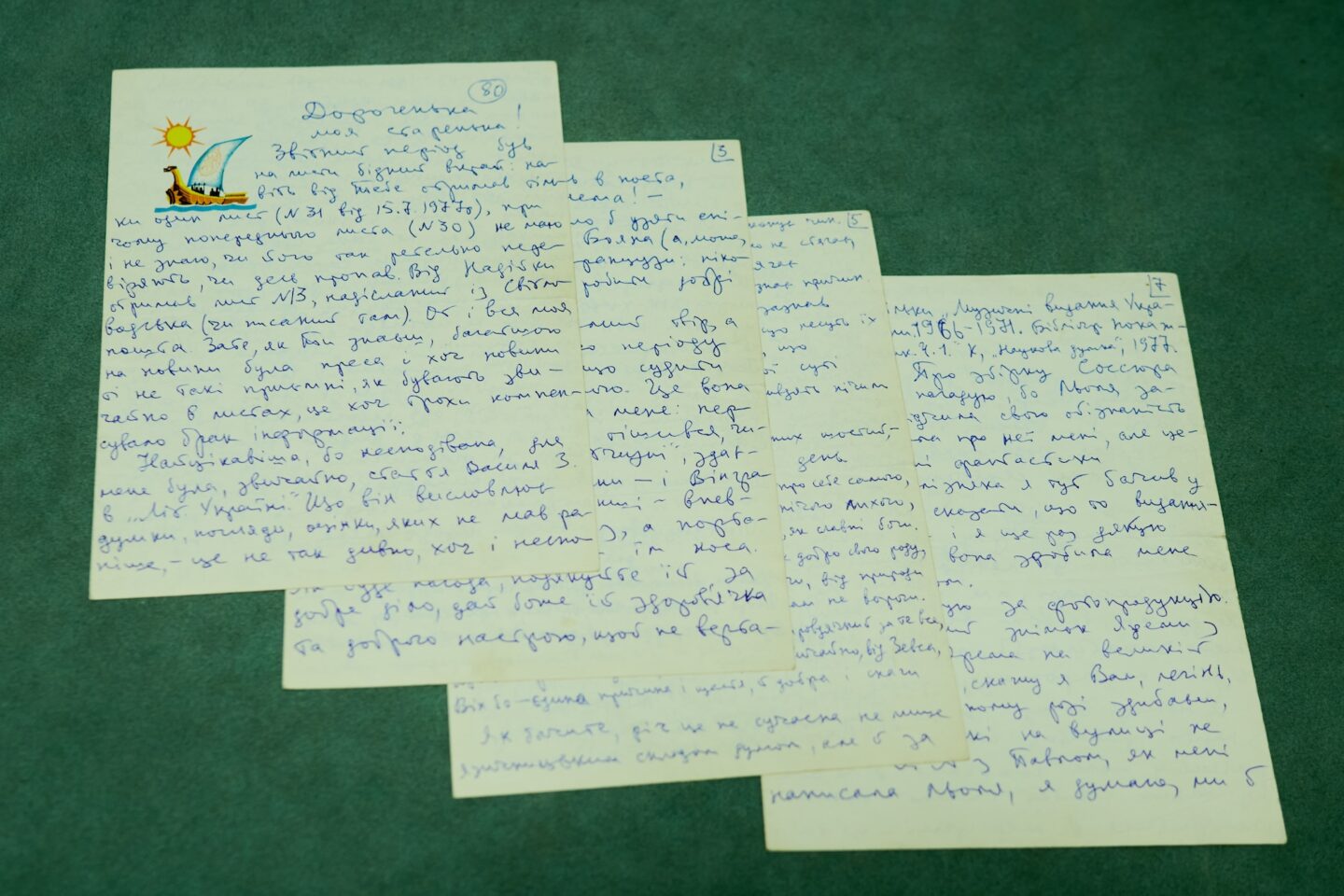

In mid-July 1973, Ivan was sent to the labor camps in the Urals. Liolia wrote him letters every five days. She put a number on each one to check whether it had arrived. Ivan wrote back twice a month. Long, long letters, sometimes as many as 20 pages. He’d ask about his friends, the processes in literary circles and recount what he had read.

Due to censorship, they developed their own language. If Ivan wrote about “receiving Leopold Ivanovich’s treatment,” it meant that he was on hunger strike. If there were no letters for a long time, it meant that Ivan was in a “cell-type confinement” (PKT), from where he was allowed to write one letter per month, or in solitary confinement (SHIZO), from where correspondence was completely prohibited.

In September 1973, Liolia traveled to visit Ivan. They had not seen each other since his arrest in January 1972. Liolia wanted to be there for Ivan’s birthday on September 20. She flew from Kyiv to Perm, and from there she took suburban trains with transfers to the station closest to the camp, Vsesvyatskaya.

The train arrived at night, and there was nowhere to stay the night, so in the morning she took a bus to the village of Tsentralnoye, where the 35th camp was located. She waited another day at the camp itself. They wanted to talk about everything, but they were fully aware that even the walls were listening.

Liolia spread butter on bread, and they wrote their most secret thoughts to each other on the butter with hairpins.

After the visit, Liolia was subjected to a humiliating search. They ripped her skirt. They tore the soles off her shoes. She managed to avoid a gynecological examination.

“My dearest, precious one!

I am writing this letter to you on Your day, on Our day, on the holiday I value above all other holidays. I am writing early, a little ahead of time, so that I am not too late. I am writing on roses and lilacs, painted ones, of course, but I would like to present to You the real ones. I want to… But many of the things I want are not possible now. And it is still unknown what was more abundant in my roses, which were not so often gifted — petals or thorns; I did not value the joys of life very much and did not bring You much joy anyhow…

But today, on Your day, on Our day, I’d like to present you this triolet:

Long live today, long live forever!

Zygzytsia, Yaroslavna, Lada!

You are my gold, my Eldorado!

Long live today, long live forever!

Within the whirl of life’s endeavours,

Hold your head high, and play staccato.

For years and years! Long live forever!

Zygzytsia… Yaroslavna… Lada…”

13.3.74.

There are many more sentences on eight postcards that do indeed depict flowers and lilacs, as Svitlychnyi describes. The letter was written 20 days before Liolia’s birthday.

Signed always: Your Ivan.

In 1974, Ivan endured prolonged hunger strikes throughout the year. In October, on the 56th day of his hunger strike, Svitlychnyi was transferred from the camp. Liolia received a postcard from him:

“Dear Liolia!

I’m being transferred, going on the Moscow train. Do not know where. I’ll write when I get there.

Cheers to us.”

19.10.74. І.S.

23.10.74. — “I’m being taken to Kazan. І. S.”

On November 10, Ivan was taken not to Kazan, but to Kyiv. He weighed 44 kilograms (before imprisonment, he weighed 70). On November 22, Svitlychnyi was allowed a general visit [a non‑private visit with relatives present — Auth.], and Liolia cried then — her Ivan was emaciated.

“My dear old love.

I address You thusly by tradition, but it turns out that You are not as old as You pretend to be. I told You that I always had before me this visage of my sad, exhausted, even gray-haired other half that came to visit me in the Urals, and I thought that You had remained that way. Yet, this time, I was pleased and delighted to see you looking fresh, composed, even rejuvenated.

During the visit, You spoke extensively about my health. I share Your concern, but there is no need to exaggerate; there was and is nothing alarming, and I am not as thin as You may think: in the month before our meeting, I managed to gain half a pood [eight kilograms – Ed.] in trying to get back to how I used to be, but I consciously do not want that. I feel better, more productive in my current shape, and my blood pressure is stable. And my head doesn’t hurt as often…”

2.12.74.

On December 15, Svitlychnyi was sent back to the camp — he was held in Kyiv for a month. In April, Liolia visited him again. They allowed her in for one full day. In total, during his seven years in the camps, they had five full days together:

“Dear Liolia!

I am terribly late with my letter to You, but the fault is not my own: I wrote to You twice, and my letters got confiscated twice. So now I won’t write anything anymore.

I’m awaiting Your arrival. When I said that mom wants to visit, I didn’t mean she should come in your stead. The wife is irreplaceable. I think You understand that. And You should never think otherwise — I await You more than anybody else. May my mother and Nadiya split the second spot…

Your I.”

24.08.76.

The exile

On May 13, 1978, his term in the camps came to an end. Svitlychnyi spent an entire year in the hospital there. He was admitted due to cerebral vasospasms and contracted hepatitis in the hospital.

Svitlychnyi was sent into exile a week earlier than expected. For the first time in the camp’s history, a prisoner’s belongings had to be transported by horse — Ivan had collected that many books, magazine clippings and other materials. Before that, he had sent over 200 kilograms of books to Kyiv by mail.

Ivan was transported alongside criminals. They helped him carry his belongings and provided him with food: “Here you go, old man, have some sugar — you can’t be eating the rotten fish.” At that time, Ivan Svitlychnyi, A.K.A. “old man,” was 49 years old.

Ivan served his exile in Altai, a place with low atmospheric pressure and oxygen deficiency.

The village didn’t even have a nurse. Given Svitlychnyi’s health condition, it was a death sentence. Liolia remembered how Ivan suffered from nosebleeds that came on suddenly as he was simply walking in the street and even while he was sleeping: “In the 70s, during his imprisonment, the nosebleeds stopped, but the headaches got worse. When I asked the KGB officers if Ivan had nosebleeds and needed handkerchiefs, they took it as a joke. Fellow camp inmates recall how often Ivan complained of headaches; sometimes he couldn’t even speak, only touch his head with his hand. In his letters from the camp, he often writes about headaches and cerebral vasospasms. Once, he had a seizure in the camp and lost consciousness.”

But Ivan persevered. He worked as a security guard and spent his free time writing. He wrote letters to his wife:

“Long live the best woman in all of glorious Kyiv and its surrounding areas!

Yesterday was a day of much celebration — I received two letters from You (four in total) and also from Mykhasia, Golden Raya and my grandmother from Uman.

As you can see, the finest women in all of Ukraine have not forgotten me here, and despite my sclerosis, I have not forgotten them, simply because I never stop thinking about them.

My health has improved, but only to the extent that it ever improves when I go to the hospital…”

27.02.79.

In May 1979, Ivan was granted leave to visit Kyiv. It was the first and only time since his arrest that the Svitlychnys had walked around the city together. They were followed everywhere. Even when they went to visit Liolia’s mother’s grave, they could see the heads of KGB agents peeking over the fence.

Starting in June 1979, Liolia was constantly with Ivan in Altai. He was given a job as a security guard and housed in a dormitory with alcoholics. However, Svitlychnyi continued translating and worked on a thesaurus, which was never published.

On September 20, 1979, Ivan turned 50. He received over 50 telegrams from three different corners of the world. The Svitlychnys celebrated together, just as they would later celebrate their silver wedding anniversary on January 31, 1981.

In February 1980, Ivan was transferred to Maima, a district center near Gorno-Altaysk. He was housed in a 12-square-meter hut with the militia officer assigned to keep an eye on him. He got a job as a bookbinder at the regional library.

Those were his last happy days — if any time in exile can be happy.

Happy days in a dormitory full of thieves and drunks. But Liolia was there with him. And there was a map of the Soviet Union above his bed, marked with the whereabouts of their friends who were also in camps and serving out their exiles.

“Ukrainians have occupied Siberia,” Svitlychnyi would laugh under his breath, and Liolia would join in his laughter.

And then Ivan had a stroke.

Nine months in hospitals

It was August 1981. The mail had arrived, Ivan lay down to have a rest and asked Liolia to read him a letter. He fell asleep while sitting. Suddenly, he fell on the floor. Liolia called an ambulance. An hour later, a nurse arrived and called a doctor. The doctor diagnosed a stroke and said he was in no condition to be transported. Nevertheless, he was taken to the district hospital. He was clinically dead. The next day, more than 24 hours later, he underwent brain surgery.

Liolia walked under the windows of the operating room. The doctor came out to her: Ivan was still alive.

They let her see Ivan only three days later. The doctor said that only 5-10% of patients survive such operations and advised her to call his relatives to say goodbye. Ivan was getting transferred from hospital to hospital. New ailments were discovered and new diagnoses were made — brain cancer, spinal sarcoma. They treated him so much that he contracted a staph infection. After an electrophoresis treatment on his neck, Svitlychnyi had another stroke. He lost movement in his right arm and became unable to speak.

Liolia was always by his side. Nine whole months in hospitals. She brought food to the patients, and in return, got free porridge and soup. She wrote letters to the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada, asking them to allow Ivan to be transferred to a hospital in Kyiv. She was refused.

She asked for his term of exile to be shortened due to severe illness. Nobody listened. The Svitlychnys served out their exile until the last day.

Before leaving, they were warned: “No demonstrations among the welcoming party!” Ivan, who was almost immobile, unable to write or read, was still feared by the all-powerful state. Liolia wondered: what demonstrations? If even one person came out to help carry Ivan up to the fifth floor to their “dovecote,” it would already be enough. All their friends were either in prison or hiding in the corners of their homes — they were afraid. Valeriy Marchenko met the Svitlychnys. He happened to be in Kyiv between his own prison terms.

Home

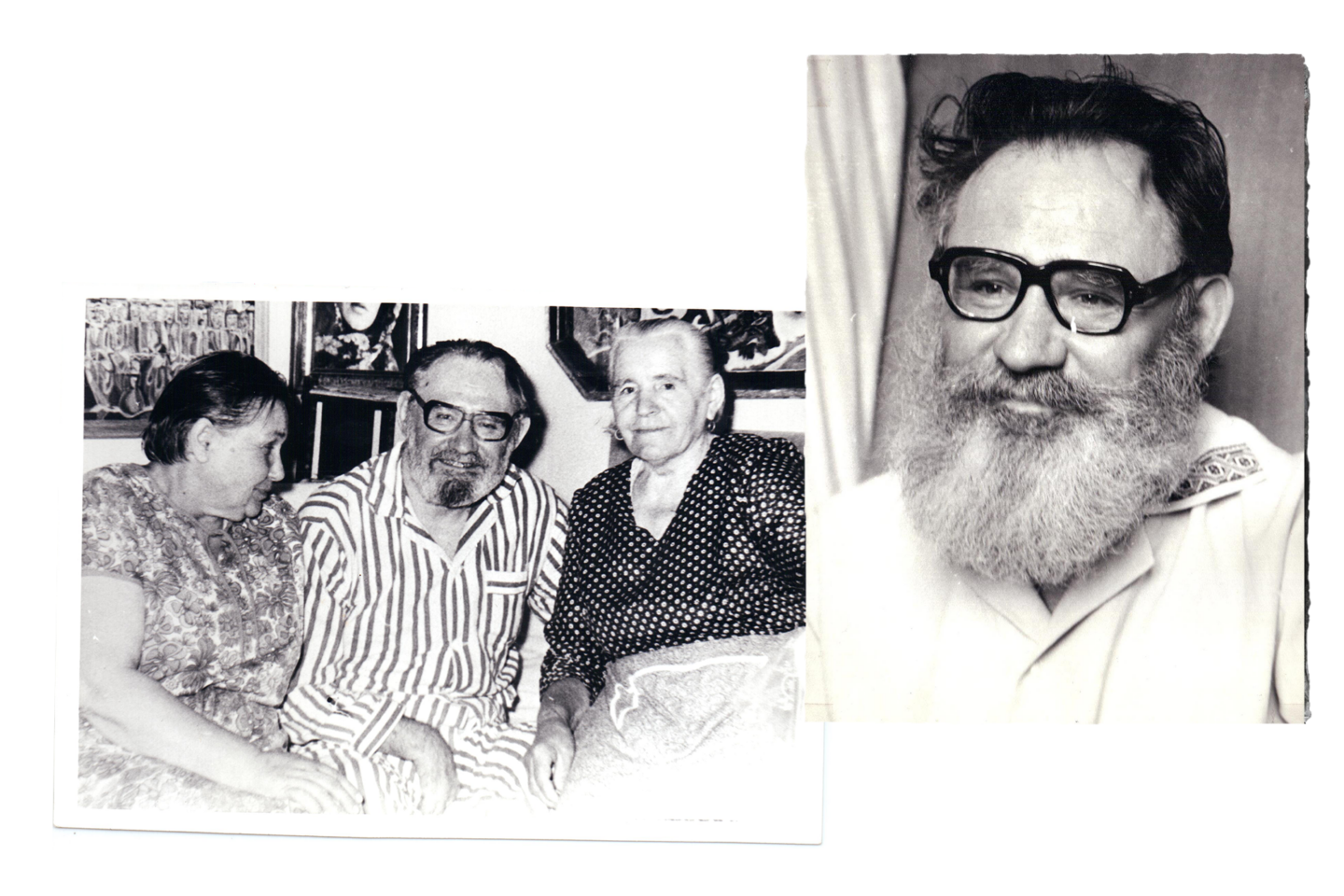

At home, Ivan hoped that his condition would improve. He asked Liolia to buy him books. He still remembered letters and could put a few words together. He listened to the radio and classical music, especially Bach. Or Nadiya on Radio Liberty; by that time, she had already managed to escape to the United States.

Ivan hoped that their “dovecote” would be what it was in the past, with poetry readings and literary evenings, hosting crowds of creative young people. But of his former friends, only those who were not intimidated by the KGB came to visit: Mykhailyna Kotsyubynska, Halyna Sevruk, Semen Hluzman, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Nadiya Odarych, Helya Ponomariova, and Ira Piievska. There was also Zinovii Krasivskyi, who welcomed them into his home in Morshyn for several months every summer. This allowed Ivan to have some fresh air and spend time outdoors.

The rest of the time, the “architect of the Sixtier movement” (as Mykhailo Horyn called him) and “the driving force of the Sixtiers” (in Bohdan Horyn’s words) was constantly confined to his apartment. He was able to move around the room on his own, but was unable to descend from the fifth floor of the building, which didn’t have an elevator. Liolia requested a change of residence, applying for an apartment exchange. However, the Svitlychnys were granted a different apartment only in 1991, shortly before Ivan’s death.

During his last three years, Ivan lay motionless, unable to talk. Only the expression in his eyes or the squeeze of his left hand could communicate to Liolia what he wanted.

One day, there was a knock at their door. A girl stood on their doorstep. It was Ivanka Krypiakevych, the daughter of their friends. She had come to make a choice — get married or join a convent. For some reason, she felt that the right answer would come to her only in this apartment filled with books, where Ivan lay critically ill on the bed, with Liolia by his side.

Ivanka gave Liolia a chance to take a break. While she was running errands or simply resting during the day after a sleepless night, the girl sat next to Svitlychnyi. One day, he grabbed the cross she wore around her neck. It was a dark wooden cross from the Garden of Gethsemane. That moment was significant because by that point, Ivan could hardly move. Ivanka suggested that Liolia call a priest. So they did. They prayed together. The priest gave Svitlychnyi the sacrament of reconciliation. Everyone was full of inspiration and at peace.

In late October 1992, Ivan’s condition deteriorated sharply. Liolia understood this was the end, so she called for his sister Nadiya to come from America and his sister Mariya from Polovynkyno; Ivan’s mother was too weak to travel to Kyiv. Nadiya did not arrive in time to say goodbye.

Ivan lay in his bed. Liolia read to him a poem by Vasyl Stus, whom he loved very much and whose death he mourned deeply. “I cannot live without Ivan’s smile,” Liolia had read. Ivan cried and squeezed her hand… Fifteen minutes later, he lost consciousness. On October 25, 1992, at 5:45 p.m., his heart stopped beating.

Ivan Svitlychnyi was buried in the Baikove Cemetery. He was dressed in a vyshyvanka, which Vasyl Stus had once gifted him. He was laid to rest not far from Stus’ grave. They say that Les Taniuk said at the cemetery: “The best thing to happen to you, Ivan, is your funeral!” — because so many people attended it.

However, Ivan’s funeral was certainly not the best thing that happened to him. That would be Liolia.

Ivanna Krypyakevych, now Dymyd, the same girl who knocked on the Svitlychnys’ door in the early 1990s when facing an important choice in her life [Ivanna married a priest and gave birth to five children — Auth.], stands with me at the grave of Ivan and Liolia. It is a pleasant autumn day. Red viburnum berries hang over the Svitlychnys. Ivanka takes children’s books out of her bag — the ones her uncle Ivan gave her when she was a child. Rudyard Kipling’s “How and Why.” She reads it aloud. “Listen to this wonderful translation!” she says to me. Ivanka suspects that Svitlychnyi himself translated it, but the book is credited to another translator — those were the times when some people translated to earn a living, while others assigned their names to their work.

Ivanka lights a candle. And she recalls: “Liolia shone brightly and burned steadily. I have never seen a steadier woman in my life. Her husband’s mangled body in her arms; he can no longer speak. At the end, he just lay there, and she put a board under him so he wouldn’t fall out of bed. She took care of him. Ivan would suffer spasms. He groaned in pain, screaming horribly, but it was unclear where the spasm occurred, where the pained muscle was. He couldn’t explain where it hurt. She massaged him, looked for doctors, medicine and scurried around. She spent sleepless nights staying by his side. I witnessed this struggle. You couldn’t call it a struggle against illness; it was a struggle against Ivan’s slow death, which lasted from 1984 to 1992. It was service on her part. But she didn’t see it as a sacrifice. It was her whole life.”

To me, you were all you were capable of being:

My Easter Sunday and my Monday,

My guarantor of “everything will be okay”,

The dewdrop on a stone

And the stone itself — solid corundum.

This is what Ivan Svitlychnyi wrote about his Liolia.

Leonida Svitlychna outlived her husband by eleven years. Following Ivan’s death, she published his books, letters, and memoirs. In 2003, she was laid to rest beside him.