How should a museum that deals with collective trauma operate? This question has remained sensitive for Ukrainians for a long time, and it was only during President Yushchenko’s term that the Holodomor Museum project was established as a research institution, a space for remembrance and an exhibition venue meant to properly address the genocide of Ukrainians in the 20th century.

The memorial complex commemorating the victims of the Holodomor is being built in several stages and continues to evolve even amid the full-scale war. The museum’s mission is to warn society about the crime of genocide by gathering and sharing knowledge about the Holodomor.

We spoke with Lesia Hasydzhak, a researcher and the acting director of the Holodomor Museum, about the collective trauma of famine and how it shaped Ukrainian resistance in the current war, as well as about the museum profession and Ukrainian sovereignty.

§§§

[This interview was made possible thanks to the support of The Ukrainians Media community — hundreds of people who believe in independent, high-quality journalism. Join to help us keep creating meaningful content]

§§§

The Holodomor Museum is an institution built from scratch. What did that mean for this museum, and did it have any advantages?

Our advantage was that we weren’t weighed down by Soviet baggage — heavy to shoulder, but just as hard to leave behind. There are no random objects in our collection because every item is connected to a story related to the Holodomor. We do not simply collect everyday objects from that era; we are not an ethnographic museum. Every object in our collection has been “filtered” through human life and human tragedy.

Our museum opened in 2009, and compared to earlier projects, it offered another advantage: a new generation of museum professionals who had experience but did not carry Soviet views on history. Our first tours were conducted by staff from the Kyiv History Museum, who provided patronage support.

And what is the best way for the state, the public sector and business to cooperate in creating large museums? What does that look like in your case?

We are a prime example of such synergy. In 2017, in response to public appeals, the state resumed the second phase of construction — intended to produce a new, large standalone building with the main exhibit, an exhibition hall, a conference and cinema hall, storage facilities and more. The state was responsible for building construction and interior work, and it carried this out successfully until Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022. After that, the public sector and business stepped in through a charitable fund to support the creation of the exhibit.

Here’s what that means: the Holodomor Museum International Charity Fund led a fundraising campaign that brought in contributions from Ukrainian philanthropists. Those funds were used to develop the introductory artistic concept for the main exhibit in our phase II building. That concept is now complete. It was created by an international design consortium and is a high-quality product we simply would not have had without the involvement of businesses and the public. Construction is currently on hold because of the war, but we are ready to move ahead with the design project and subsequent stages of conceptualizing and producing the future exhibit — work I hope will be realized as part of an international technical assistance project from the Canadian government, with the Holodomor Museum as the recipient.

We began researching the Holodomor too late. Survivors alive today were 4 or 5 years old in 1933, which means their memories of that time are far less detailed.

How did you come to be involved in researching the Holodomor? Were there any stories from your family or the families of close friends that influenced your understanding of this tragedy?

I first heard about the Holodomor when I was about 10 years old, in third or fourth grade. Fortunately, my family was not directly affected… I became more deeply involved with the topic in my third year at Taras Shevchenko University. It was 2003, and Professor Valentyna Borysenko suggested that those who were interested should interview Holodomor survivors.

So the summer of 2003 turned out to be quite eventful for me: first, an expedition to Crimea, where we interviewed Crimean Tatars about their deportation and return to their homeland; and afterward, trips to Poltava and Donetsk oblasts to interview witnesses of the Holodomor. That was the second time I encountered this topic — this time as an adult.

How important is the discovery of family history for your museum? Does visiting your museum contribute to the process of connecting individuals to collective memory?

Yes, of course. Many of those who come to our museum consciously stay in touch with us afterwards. My colleagues communicate with those people, record family histories, or, as I mentioned before, persuade them to give us their elderly relatives’ personal belongings as items for our exhibit. Sometimes we communicate with entire communities, as they look for more information about the victims of the Holodomor in their region.

Often, after such communication, the community decides to establish or renovate a memorial in honor of people killed by famine.

Here is a story from last year. A journalist, a friend of ours, contacted us and told us that a memorial to the victims of the Holodomor had been erected in a local cemetery near Pokrovsk during Yushchenko’s presidency. The Russians were already approaching the site, and this journalist suggested that the memorial could be moved from Pokrovsk with the help of the military. Of course, I agreed. We knew all the details about this property, who it belonged to, and which government institution was responsible for it. It was important to remove the monument — later we could decide whether we’d simply store it or temporarily install it on our territory. After all, we monitor the situation and know that in the occupied territories, the Russians are carrying out demonstrative dismantling and destruction of memorials and monuments that symbolize the truth. But events unfolded in such a way that within a few days, the area became reachable by machine-gun fire, and due to the obvious danger, we had to abandon this plan.

That’s such a pity.

Yes… And to answer your question, I will tell you about our employees’ involvement in family histories. A month ago, we began a major expedition across Ukraine. It was made possible as part of the Canadian government’s international technical assistance project, “Support for exhibits of the National Museum of Holodomor in Kyiv.” Two field groups covered eight routes in the Odesa, Kirovohrad, Mykolaiv, Cherkasy, Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Volyn and Kyiv oblasts. We have seven more routes planned, but we are postponing them until spring.

My colleagues recorded 4-6 interviews per day, which, I think, is the hardest work one can do. But it was done by mega-professionals who have already conducted some 180 interviews, both with witnesses of the Holodomor and with those who experienced the post-war mass famine of 1946-1947. They are true professionals who empathize, keep the conversation going and let their emotions come through, as tears involuntarily well up in their eyes. Such presence — sincere, not feigned — is very valuable.

Absolutely. And how do you assess the evidence you have gathered? As in, do you ask yourselves — have we recorded enough, or could we have done better? Today, we know that many witnesses to the famine were too scared to talk about it until the very end of their lives. How can we as a society work with these testimonies today?

I could complain that we started too late, meaning that the main witnesses died before Ukraine declared independence. But that wouldn’t be right. Everything happened as it was meant to. We grew up and matured together with our country. Before the museum was created, various institutions recorded testimonies. There was the Association of Holodomor Researchers, and there was the Black Book project by Volodymyr Kovalenko and Lidiia Manyak, which was published before 1991. Much has been done, but it was mostly done unprofessionally — notes were taken by hand on paper, often without a recorder, and if there were audio recordings, they are now lost.

Witnesses began to be interviewed en masse around 2003, when there were still living witnesses who had experienced the Holodomor in their youth. Now, only those who were 4-5 years old in 1933 remain, and their memories are already less detailed.

But we are still trying to make recordings of everyone who remembers this tragedy.

Regarding the museum’s work in recording testimonies, what I can tell you is that to go on expeditions, researchers require a car that is capable of traveling on non-existent Ukrainian roads, transporting the researchers and their equipment, and the historical artifacts provided by respondents back to the museum. And the museum does not have such a car. All expeditions are always undertaken with the employees’ own resources, as they either travel by public transport or in their own cars. It shouldn’t be like this.

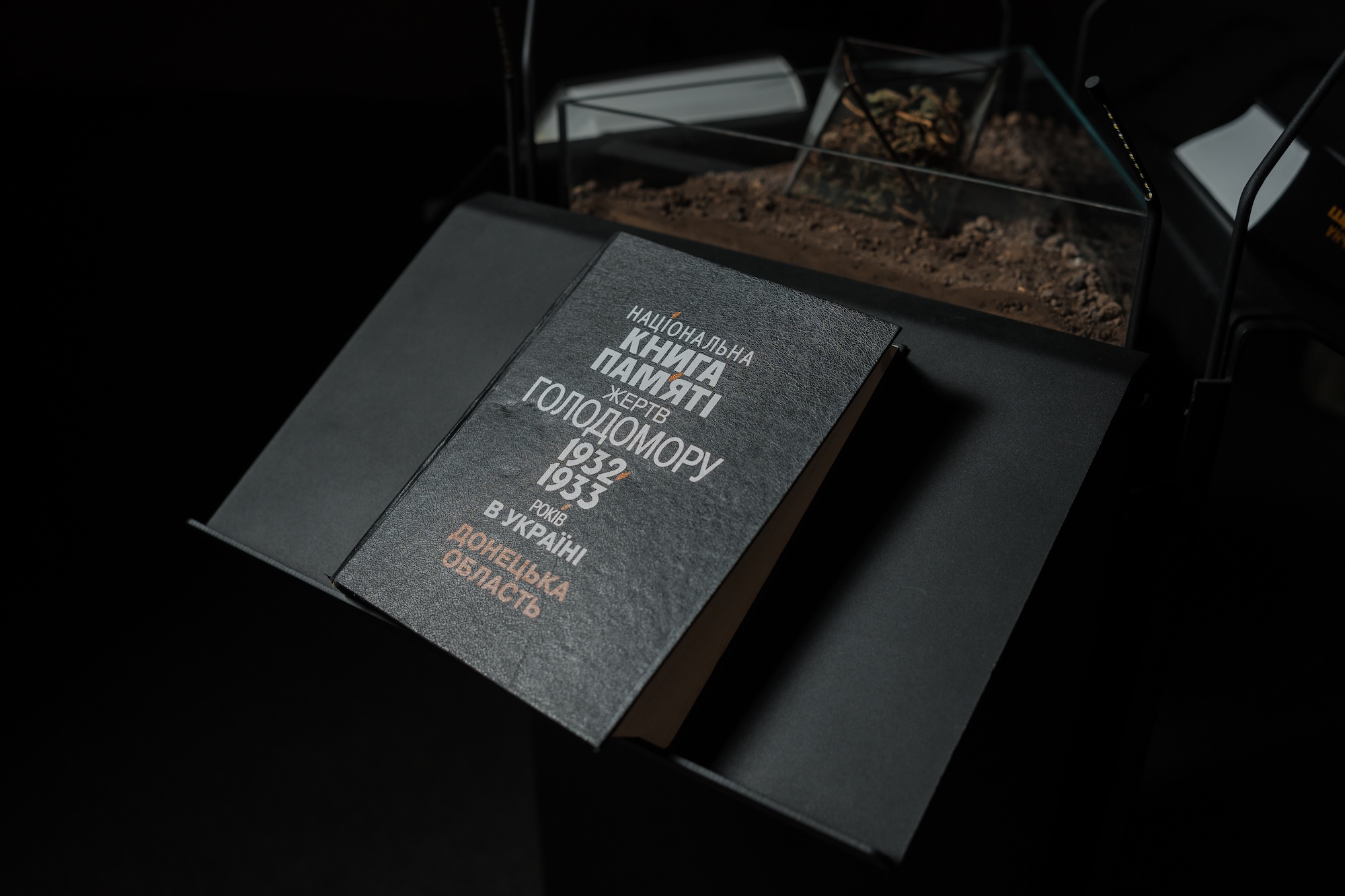

We currently have about 5,000 such testimonies, which is the largest archive open to the public and accessible to journalists and teachers. We transcribe the testimonies and post the video along with the text on our website. How should people engage with this material? First of all, it is important to remember that there has not yet been an international tribunal on communism as an ideology. These testimonies are evidence for such a tribunal. We don’t know when it will take place, or whether it will take place at all, but we have already laid the groundwork for an indictment of communism. The Genocide Convention has no numerical restrictions. A crime of this kind, whether it was committed against a million people or a thousand, remains the most egregious.

Do we know the names of those responsible for the Holodomor? And I don’t just mean figures like Stalin, Molotov, Kaganovich, etc., but also about Komsomol leaders who headed the “red gang,” shaking down their fellow villagers for grain. How do you work with the memory of Ukrainians who carried out this crime?

This relates to your previous question about working with the Holodomor testimonies. It is precisely from the memories of witnesses that we can learn the names of the perpetrators. Because in interviews, people name those who went from house to house, mocked them, and took away their last possessions. Often, they were neighbors or fellow villagers. There is no comprehensive register of such individuals. Obviously, creating one is an important task, but even without it, everyone in the villages remembers those names to this day. Sometimes people explain someone’s difficult fate by saying that their great-grandfather abused others while in a position of power on the collective farm and received punishment for that. Many people know what roles their ancestors played. But they are not yet ready to talk about it publicly.

Wouldn’t it be better to create a register of those who saved Ukrainians from starvation? Those who, perhaps, adopted other people’s children or something like that. In other words, to create a register of the righteous, similar to the one that exists in the context of the Holocaust.

I raised this issue in 2022. My idea was to introduce an award, even posthumously, for those who saved people from starvation. We had several meetings at the Ministry of Culture and the Institute of National Memory, but we did not make any progress, because in many cases, the perpetrators of the Holodomor were themselves the rescuers. That is, the heads of collective farms, school principals, and MTS managers — at some point, they saw the light and provided food to the workers, a bowl of soup to take home to feed their families. Or they organized nurseries or kindergartens, where they also fed the children a little.

Was that just the duality of human nature or an attempt to absolve themselves of their sins?

Those people believed in the communist ideology. They were Ukrainian communists — like all those brilliant artists who agreed to serve the government and Stalin in exchange for apartments in Slovo House, but did not take into account that everything has its price. But that is only one reason. The second is that history has often failed to preserve the names of those who saved people from starvation. There is only a small percentage of rescuers whom we can name by name — for example, priest Oleksiy Voblyi from the village of Piskoshine in the Zaporizhzhia region. We talk about him during our tours.

The perception of the famine of 1946-1947 is quite distorted. Many believe that the famine of the 1940s was a direct consequence of the war. However, that is not entirely true.

The Holodomor famine of 1932–1933 had an exceptionally severe impact on the Slobozhanshchyna and Pryazovia regions. Ethnic Russians, including those with criminal records, were subsequently resettled in the depopulated villages of this region, changing its social composition. How did the famine as a collective trauma affect this historically Cossack region, and how did it change it?

I would like to refute these claims. Yes, the media likes to spread the idea that our eastern and southern regions were repopulated by Russians by literally putting them in the empty houses after the Holodomor. But historian Hennadiy Yefimenko proved this to be untrue a long time ago. Although Russians were brought there in droves for assimilation, as evidenced by archival data, in most cases, they went back to where they came from. We know this when it comes to the years 1933-1935.

However, the real Russification of Slobozhanshchyna and Donetsk Oblast took place later, after World War II.

Under the slogan of rebuilding the Donbas industry, young people from all over the USSR flocked to eastern Ukraine, as did the criminals — yes, that is true! — who had been released from prison. They sought to hide and assimilate in the regions that were rapidly developing and accepting streams of people from all over the Union. There, in a single cauldron, they tried to forge the “new Soviet person.”

Let us not forget, though, that there were also political prisoners who, after serving their sentences, were forced to settle in Donetsk Oblast because they often did not have permission to return to their home regions.

The artificial famines of the 1920s and 1940s are less extensively researched. The latter has more living witnesses. What is being done to study the famine of 1946-1947, whose 80th anniversary we will mark next year? What was its scale in terms of victims?

As I have already mentioned, during recent expeditions, museum staff have gathered sufficient evidence regarding the famine of 1946–1947. I believe that it is time to publish a joint monograph based on the obtained evidence and previously disclosed archival data.

I would like to note that the perception of this famine is quite distorted. Many believe that the famine of the 1940s was a direct consequence of the war. However, that is not entirely true. The authorities could have prevented it from reaching the scale that it did, just as in the 1920s. But they did not open up internal reserves for Ukrainians, or — as in the case of the famine of the 1920s — they did not accept international aid for a long time, and when they did, they redirected it to the Volga region, which led to such a high mortality rate.

What was the number of casualties during the famine of 1946-1947?

From 500,000 to a million people.

Are there any other museums dedicated to famine in the world besides the famous memorial in Ireland? Did you use it as a reference when you and your colleagues were developing your concept for the Holodomor Museum?

No, we did not use the Irish experience as an example. In Ireland, famine occurred due to potato crop failure and the colonial policy of the British government, while in Ukraine, genocide was committed, one of the tools of which was famine caused by the forcible seizure of grain and food from people, as well as resorting to a whole host of criminal actions. That’s the short version. These are two different stories and different dimensions. That is why our approach to museum work is different from that of the Irish.

How do the testimonies of Ukrainians who were tortured by starvation in captivity and prisons in the Russian Federation relate to the work of the museum?

We are just beginning to work on this. We plan to bring together scholars and discuss ways to give space to these testimonies without pivoting the museum’s concept to military history. Because these are different events, even though Russia’s war against Ukraine is also genocidal. We must first win this war, then reflect on it and only then create a museum for it. That is my position. But in our exhibit, we will make specific references to the present, and we have already recorded such testimonies.

Theorists of memory emphasize the importance of understanding collective traumas that are part of national identity. What else do we need to reflect on about the great famine in Ukraine?

I am convinced that we are not victims. We are an unbreakable nation that has survived despite everything. In fact, the museum’s second phase premises were supposed to contain stories of successful Ukrainians whose families survived the Holodomor. All of them were born precisely because their ancestors did not give up and survived. The grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these people are now fighting for Ukraine’s right to exist. This is how the Holodomor should be understood — as a tragedy that strengthened the nation over several generations and tempered it for the fight against the descendants of our lifelong enemy.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Liubov Kukharenko