This audio is created with AI assistance

§§§

[This interview was made possible thanks to the support of The Ukrainians Media community — hundreds of people who believe in independent, high-quality journalism. Consider joining to help us create meaningful content.]

§§§

I live practically on the river: the Dnipro is just two minutes away by bike and four minutes on foot — seven if the streets are iced over. This winter, for the first time in several years, the stretch of river where the sandy beach meets the rapid current froze solid. I learned this when we lost our last functioning utility: cold running water. “I’ll fetch some from the Dnipro,” I thought. Now I know that in an emergency, it’s better to take water from Lake Telbin, where ice fishing holes can be found no matter the weather. There are many bodies of water in my area, and that feels symbolic. Much of what is now the Berezniaky district, along with neighboring Rusanivka, was built on reclaimed land in the late 1960s. We are Kyiv’s anti-Atlantis — we rose from the depths, and we don’t plan on drowning.

When you live on the Left Bank, you get used to hearing endless comments about how it’s not really Kyiv. In some respects, that’s true — we’re like a satellite orbiting a planet. Yet this satellite has already absorbed the suburbs and is approaching the Right Bank in population, if it hasn’t already surpassed it. When the air-raid alert sounds, it feels as though we are locking ourselves behind a massive gate, cut off from everything else. Getting from the Left Bank to the Right becomes almost impossible: there are very few marshrutkas, and their routes mostly end at Left Bank metro stations. The metro itself doesn’t run across the bridges, and the bus route has only two buses, so no one knows how long the wait will be. Taking a taxi could cost as much as a ticket to Lviv — and that is no exaggeration. So if we can help it, we prefer to stay put.

The Left Bank is an autonomous entity. We have our own coffee shops of every tier of trendiness, our own parks, lakes and cinemas. Our cats are fluffy and brave; our ducks don’t migrate south, choosing instead to huddle together on the ice of Lake Telbin. Even our lake-dwelling turtles are a stubborn bunch, as if Darwin himself had dropped them here. On the Left Bank, blackouts are measured not in hours, but in days.

“I haven’t had power for two days,” I tell my trainer at the gym.

“I’m on my second day now,” she replies dispassionately. Neither of us will be washing our hair at home today.

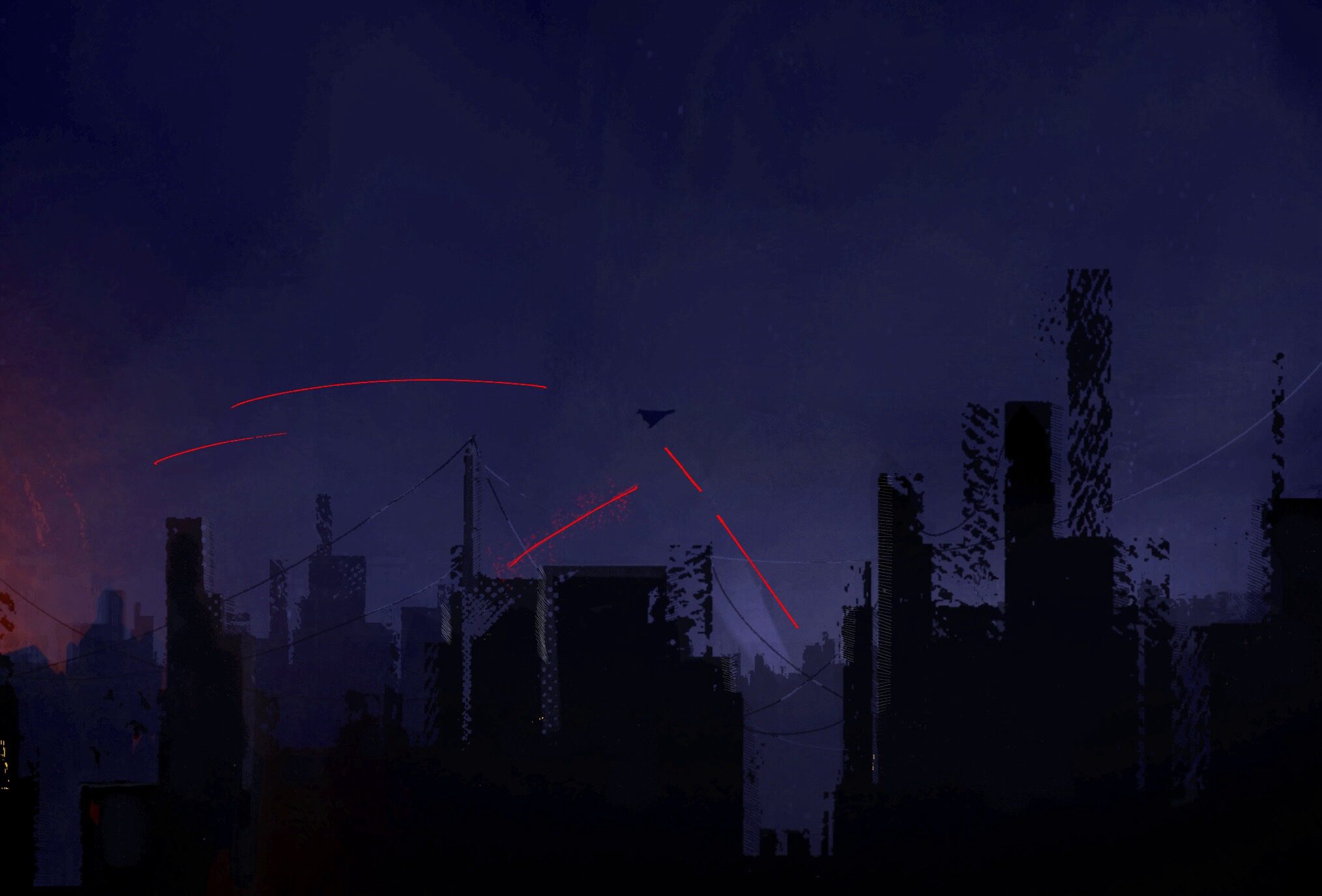

The surrounding neighborhoods get their power and heat either from the legendary Darnytsia CHP or from the lesser-known, but no less frequently targeted, Vydubychi CHP. When a CHP is hit, you know it immediately: the distinctive sound of water draining from the radiators, an instant blackout across the entire neighborhood, the buzz of Shahed drones outside the window, loud explosions. Then, total darkness. Crossing the Paton Bridge from the Right Bank to the Left feels like plunging into a vat of extra-dark Vantablack paint, as if it were invented specifically for our reality: not a single light, only the monotonous hum of diesel generators. Yet behind the darkened windows, life goes on. You can still buy a potted hyacinth (how could one survive a blackout without it?) and freshly squeezed orange juice at Silpo in the Silverbreeze mall. Pet shops offer new treats for your cat. On weekends, children sled down the banks of Lake Telbin — some on proper sleds, others on ATB plastic bags. In the mornings, grandpas head out ice fishing; the day they disappear from the streets will be the day I start to worry in earnest.

This winter, I experienced a days-long blackout for the first time. In the morning, everything seems normal: the water in the boiler is still warm, the laundry basket isn’t quite full enough for a load, and there’s still plenty of charge in the powerbank and water in the bottles. As you leave for work, you habitually leave all devices plugged in — maybe there’ll be power for at least an hour, just enough to charge them up. When you return, the EcoFlow battery is only half-charged, the radiators are ice-cold, and the bottles of ice haven’t even begun to melt. The main advantage of these 1970s-era apartment blocks is their gas stoves. Their drawback is the nonexistent insulation — they cool down very quickly.

After 20 hours without heat, you accept the terms of your predicament and pull out a third blanket; after 30, a sleeping bag meant for harsh winter hikes.

Thirty-five hours in, the internet finally goes down; now you’re on your own, and the Right Bank no longer exists. You walk around the apartment without a jacket, but wearing a T-shirt, thermal underwear, warm pajamas and two sweaters. The cat, who once pretended to be independent, crawls under the three layers with you and huddles close. The thermos suddenly weighs more than it ever has, and bringing over boiling water becomes proper etiquette when visiting someone’s home. Meals are dictated by which food will spoil first, and you wear whatever is warm, not whatever is clean. Forty hours in, you fashion a warming station from candles on a tray. Forty-two hours in, you go to the hardware store to buy fire-resistant bricks — the hottest trend on Ukrainian social media. The EcoFlow power charger is an extremely convenient but heavy piece of equipment, and when there’s no power at all, it becomes useless. You can’t haul this 23-kilogram thing to the nearest Invincibility Point to recharge it when the elevator isn’t running. So you accept your fate, linger at work where there is electricity, and go anywhere you’re invited, just to stay away from home as long as possible. By day two, social media is full of offers like, “Come live with us on the Right Bank while they fix it.” You read in the news that Sadovyi has sent maintenance crews from Lviv to Kyiv, that boilers are on their way from Kherson, and that cogeneration plants are on their way from Zaporizhzhia.

My friends in a nearby high-rise have it even worse: they have parrots. For some reason, these proud descendants of dinosaurs never learned to grow a thick coat of fur like my cat, Bisyna, and they get terribly cold. In winter, my friends always try to use a heater — not for themselves, but for the parrots. No one ever taught us how to keep parrots warm during a blackout. In the buildings a little further down the neighbouring street, water in the pipes has frozen; they have been without heat for a week, and the temperature inside has dropped to zero. Near the Livoberezhna metro station, you can see the damage from a drone strike on a brand-new condo complex. The last sentinels of the night watch — the knife and fruit vendors outside McDonald’s — haven’t shown up for work for the first time in my memory. It’s -17°C outside. At the gym, I take off my T-shirt: it’s +16°C inside, and I warm up quickly.

The Left Bank is divided into smaller clusters of neighborhoods, each forming its own community. During blackouts, this proves especially useful. Yes, it was the Left Bank where people gathered outside for a barbecue during a power outage; we are the ones who have online groups for finding things lost in the dark, learning how to warm up your apartment with a pot, salt and stones, or even buy “home-grown potatoes, delivered to your floor” — unclear if that offer still stands during blackouts. At night, when my phone’s battery drops to 10%, I check the group chat for news. The latest message reads: “Hi everyone, I’m taking orders for holiday cakes.” This is classic Left Bank. Here, people adapt quickly to blackouts and to what the authorities call a “humanitarian catastrophe.” Nothing can stand in the way of baking cakes.

I’m finishing writing this column the morning after yet another massive drone and missile attack. At night, the garage co-operative nearby was burning, and there were explosions. Once again, we have nothing — no water, no lights, no heat. Every small, almost automatic action, like washing your hands or brushing your teeth, now takes three times longer than it used to. Perhaps this isn’t the life I would have imagined for myself, but it is my life, and it goes on. I can hear sparrows singing outside, and it’s only -7°C — spring seems to be just around the corner.

Illustration by Vadym Blonskyi

Translated from the Ukrainian by Liubov Kukharenko