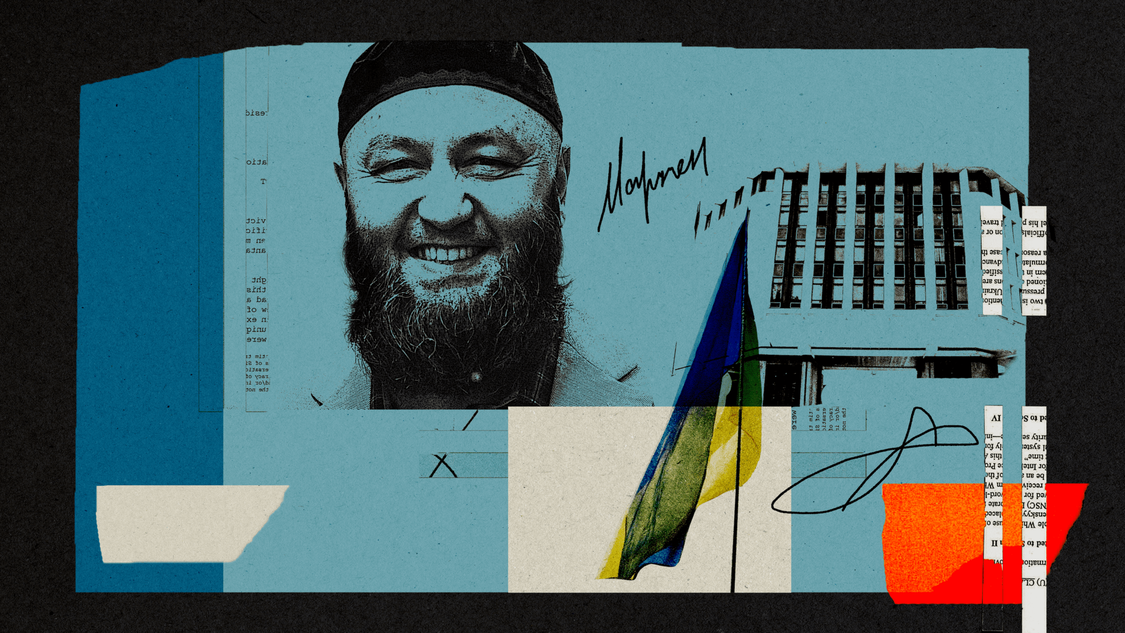

Marlen (Suleyman) Asanov was born in 1977 in Bekabad, Uzbekistan. His family, deported in 1944, returned to Crimea in the 1980s. Asanov studied philology and later taught Crimean Tatar language and literature at the Holubynske School. In 2000, he co-founded the cultural-ethnographic center Kökköz, and in 2002, he established another Crimean Tatar center—the Salachyk Caravanserai.

Since 2014, he has supported the families of political prisoners, attending court hearings in politically motivated cases and posting videos of searches on his YouTube channel. He was detained in 2017 under accusations of “organizing the operations of a terrorist organization”(Part 1, Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) and “preparing for actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power” (Part 1, Article 30 and Article 278 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation). After his arrest, Suleyman was nominated for the 2017 Volunteer Award from the Euromaidan SOS initiative.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

On October 10, 2017, as he returned home, Asanov leaned close to his four-year-old daughter, Safiye, inhaling the familiar scent of her dark hair. He whispered, “I feel for those who have been deprived of their freedom. I want every prisoner to embrace their children and feel their scent as soon as possible.”

On October 11, at five in the morning, security forces stormed his house.

Missing in action

Asanov’s great-grandfather, Asan, served in the Soviet army, like 17,000 other Crimean Tatars. Although many —such as Amet-khan Sultan, twice awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union—fought valiantly for the Soviets, it did not stop Stalin from accusing them of “collaboration” and “unreliability,” leading to their deportation from the peninsula.

Asanov’s great-grandfather never returned from the war; he went missing in action. Asanov’s great-grandmother, along with their five children, was taken to the Uzbek steppe, 4,000 kilometers away from their homeland. The family lived in a shack with scarce food. The woman worked on a farm and would leave a cup of milk in a hole in the wall for the children to drink from in turns. One day, a supervisor saw this and beat her with a whip. Fortunately, their uncle Mudzhab returned from the war and took care of the children. This helped them survive.

The first swallow of Bakhchysarai

On March 2, 1977, the cry of a newborn echoed through the maternity ward in Bekabad. Nineteen-year-old Dilyara couldn’t believe it—it was a boy! The family had only had girls, and they had eagerly awaited a son. Her husband, Refat, rushed to the maternity ward three times to confirm the news. Dilyara laughed as she showed him their three-kilogram baby through the window. They named him Marlen, a trendy name at the time.

Within a year, the family decided to return to Crimea, even though Crimean Tatars were facing deportation once again. Dilyara wanted to finish her studies in philology in Uzbekistan, so she flew from Crimea to the city of Jizzakh to take her exams.

“Marlen clung to the hem of my skirt,” Dilyara recalls of the day she boarded the plane. “I held my daughter in my arms. That’s how I studied.”

The family managed to buy a house in Crimea. But twice a week, the district officer and the head of the village council would come with witnesses, saying, “Leave. You won’t be allowed to stay here anyway. You have no residency permit, no jobs.”

It was true—Crimean Tatars struggled to find jobs. As soon as employers learned of their background, job offers would vanish. The family had no choice but to return to Bekabad.

Their second attempt to resettle in Crimea came in 1988.

“I took two brothers and a car, and we went,” recalls Refat, Asanov’s father. “We told seven siblings, in-laws, and cousins that we would settle in Crimea within a year. Bakhchysarai and Sevastopol were closed areas, but I said I would live in Bakhchysarai. That’s the city where my mother was born.”

In 1988, Crimean Tatars held demonstrations for their right to live in their homeland and for the release of political prisoners.

On May 18, the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Deportation, thousands of Crimean Tatars took to the streets in twenty-two cities of the Soviet Union. In Crimea, protests were held in nearly all districts.

Asanov’s father had been standing outside the Bakhchysarai District Executive Committee since May 12.

Eighty-seven people gathered to picket the institution, demanding the right to residency registration and their own piece of land.

They stood for twelve days, enduring rain and sun. Although the authorities tried to drive the demonstrators away, they remained steadfast.

In late May, Ronald Reagan was scheduled to meet with Mikhail Gorbachev.

The head of the Bakhchysarai Executive Committee finally came out to the demonstrators and said, “Come closer. Young men and women, today, a decision was made by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR to open residency registration for Crimean Tatars. I ask you to go home, wash up, and dress up. Tomorrow, I’ll be here to register you.”

“We’ll only leave when all our people get registration,” the picketers replied.

They did not want to take any chances and waited until morning when the documents began to be processed.

Asanov’s father says proudly of that day, “We sent the first swallow into Bakhchysarai. We waited and succeeded.”

A peaceful one

At that time, Asanov had just turned eleven. He attended school in Sokolyne (known in Crimean Tatar as Kökköz), near Bakhchysarai, until the fourth grade, after which he was enrolled in the Holubynske School, close to where the family had lived before the deportation. Later, Asanov earned a degree as a teacher of Turkish and Crimean Tatar languages and literature.

He also wanted to become a guide, immersing himself in reading about history. This pursuit brought more questions than answers.

He began to wonder: Who were the Crimean Tatars, and who was he? After decades of Russification, when any expression of an individual’s identity was punished and labeled as “nationalism,” these questions weighed heavily on him.

Learning the meaning of his name shocked him. “Marlen” was a combination of “mar”—Marxism, and “len”—Leninism. He realized the name did not suit him. Since then, he’s been known as Suleyman, which means “a peaceful” or “a protected one.”

Capturing the fleeting

He loves children, and children love him. Since 1999, Asanov had been teaching at his hometown school, and in 2000, he co-founded the cultural-ethnographic center Kökköz. He found an old house and renovated it to showcase the old Crimea and the authentic lifestyle of the Crimean Tatars. He took village guests to the fortresses of Mangup-Kale and Chufut-Kale, an ancient mosque, and the palace in Koreiz. At the end of the day, he treated visitors to national dishes.

Asanov developed tourism in his native Bakhchysarai district, conducted open lessons, organized events, and took children on excursions to keep them engaged. In 2002, he was awarded the Teacher of the Year prize.

In that same school, though with a different teacher, Ayshe, Asanov’s future wife, also took Crimean Tatar lessons. At her graduation, he gave her a bouquet of flowers and waited for her to finish medical college in Yalta so they could marry.

They created a family, and in the same year, they created something else of significance—the Crimean Tatar Cultural-Ethnographic Center Salachyk.

The name comes from an ancient settlement at the foot of Chufut-Kale, the first capital of the Crimean Khanate. The village of Salachyk disappeared from the map in 1954 due to being merged with Bakhchysarai.

Asanov found another old house, opened a mini-museum, and searched for old pottery and utensils. Every detail was important to him: he wanted to showcase Crimean Tatar culture as authentically as possible. Ayshe brewed coffee over a fire and served guests. Alongside the coffee, she offered hard caramel and parvarda. Over time, Salachyk also featured a kitchen where they prepared chebureks, pilaf, manty, tataraş, and yufakaş—miniature dumplings, seven to nine of which fit in a single spoon.

Asanov spent most of his time at work, but despite the fact that fifteen cooks worked at Salachyk, he always came home for lunch. On weekends, he took the children fishing, cycling, or ice skating. And, of course, he showed them the mountains.

He sees beauty in details and has a talent for photography. Raindrops on rose bushes, clusters of cornel or rowan berries, golden leaves or snow-covered trees— Suleyman loves capturing moments, and he even once participated in a competition titled “Bakhchysarai Through the Camera Lens.”

He also fed pigeons at Salachyk. He bought grain specifically for them. The pigeons became so accustomed to him that one day, a white dove sat on his shoulder and pecked at his earring, mistaking it for a grain kernel.

A caring man

After the events of 2014, life in Crimea changed drastically. People were imprisoned on false charges, and many were threatened.

Asanov would rush to the sites of searches, film them, and attend court hearings. He was an active member of the Crimean Solidarity. He took care of the families of Crimean political prisoners, with around a hundred children left without their providers. He helped them with their daily needs, purchasing medication and clothing and paying for medical surgeries. Whatever anyone asked for, he was always ready to help.

Ayshe explains that helping others is part of their religious philosophy.

“When the imprisonment of Crimean Tatars began, Suleyman tried to do everything possible to spread the word about the injustice,” his wife explains.

In 2017, the head of the Crimean Tatar Resource Center, Eskender Bariiev, nominated Asanov for the 2017 Volunteer Award, noting that his story serves as a “source of inspiration and a prime example of caring, action, and strength.” This annual award is given out by the Euromaidan SOS initiative, coordinated by the Center for Civil Liberties, which received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022.

Asanov’s activism as a citizen journalist unnerved the Russian authorities in Crimea. Friends advised him: “Leave.” His parents insisted: “Go, such people are not wanted here.” Suleyman stayed. However, he could not accept the 2017 Volunteer Award in person because he had been detained.

The case

On October 11, 2017, armed men stormed the Asanov family home. It was five in the morning. Outside, it was still dark. The FSB agents did not knock—they immediately broke down the door, pinned Asanov to the ground, and handcuffed him.

“I’ve never seen so many people at a search,” Ayshe recalls. “They even blocked our street so no one could pass.” She asked them, “Why are you breaking in? If you had knocked, we would have opened the door. We’re not hiding from anyone.”

The masked riot police and FSB officers turned the house upside down, pulling things out of the cupboards, unfolding the sofas, and releasing the rabbits the children kept, searching for something in the cages. The search lasted from 5 a.m. until 1 p.m. The children were crying, but they were not allowed to be taken to the neighbors.

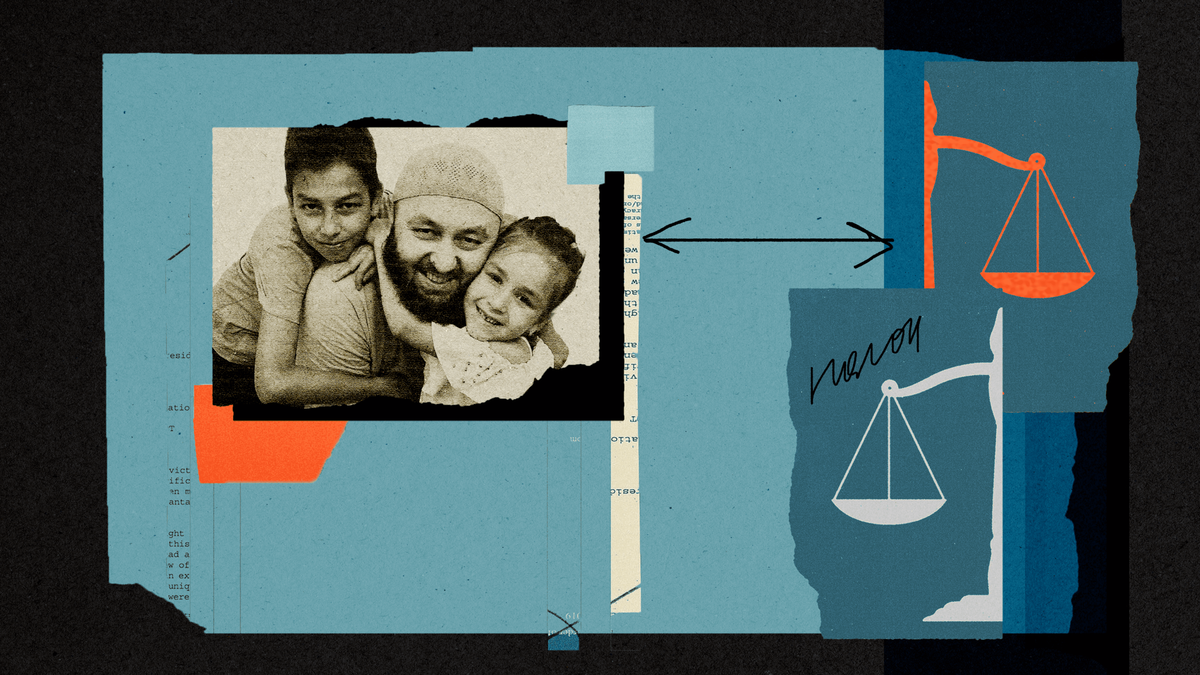

“There were consequences,” Ayshe admits. “Our middle son began to stutter and had trouble reading. It took him about two years to recover from the shock. Our daughter wouldn’t let me out of her sight, fearing that I would disappear too.”

After the search, Ayshe wrote multiple requests for visitation, but the investigator refused. For a year and a half, she and the children did not see their husband and father.

When the court hearings began, Asanov was accused of being involved with the organization Hizb ut-Tahrir and of “organizing the operations of a terrorist organization.” This was the second group of Crimean Tatar Muslims arrested in Bakhchysarai for alleged ties to Hizb ut-Tahrir. Lawyer Edem Smedlyaev explained that this criminal case was related solely to the fact that due to their active stance, Crimean Tatars do not abandon their compatriots in need. Moreover, the meetings of the Crimean Solidarity group often took place at Asanov’s center, Salachyk.

Ayshe explains that the “evidence” in the case was based on a recorded sohbet, conversation about Islamic issues.

Konstantin Tumarevich, who had come to Crimea and converted to Islam, secretly recorded three conversations in the mosque. FSB officer Nikolai Artykbayev was the prosecution’s key witness, stating that he organized the surveillance of Muslim meetings. He personally transcribed the conversations, but due to his lack of Arabic knowledge, the translations were filled with mistakes, as pointed out by both the defense and the accused themselves.

Despite the fact that Hizb ut-Tahrir was never mentioned in the conversations, the investigation argued that this very absence was evidence of the participants’ affiliation with the Islamic party—an alleged attempt at secrecy.

In 2016, when the first Crimean Tatars were arrested for alleged involvement with Hizb ut-Tahrir, lawyer Emil Kurbedinov explained that the court considered all those engaged in sohbets as members of the organization: “I went to the mufti. I said, look, we are having a sohbet right now. If we speak Crimean Tatar, does that make us members of the Hizb ut-Tahrir party too?”

“This case is full of holes,” Ayshe reflects. “There was a hidden witness who could accuse the defendant of all kinds of sins. And how can you verify that?”

On March 17, 2020, at the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don, after a hearing on the second Bakhchysarai group of Hizb ut-Tahrir, Ayshe wrote a note with the words “I need you like air” and showed it to her husband.

A court official deemed it an offense and opened an administrative case. A fine was imposed on her, though it was later canceled.

The accusations against Asanov did not align with reality. However, despite the lack of evidence, in September 2020, he was handed an unjust sentence: nineteen years in prison.

“Even when they gave him nineteen years, he had a smile on his face—that’s how strong his spirit is,” Ayshe recalls. “In the detention center, there were people of different nationalities. Someone even wanted to commit suicide, not knowing how to survive five years in captivity. But Suleyman sat calmly, smiling and joking. They asked, ‘How can you be so calm? They gave you nineteen years!’ Suleyman said that his faith helps him. ‘Only the Almighty knows how long I’ll spend here. I could be released tomorrow, or I might never be released,’ he pondered.”

Ayshe explains: “We believe in the Almighty, and that helps us keep going.”

One of Prophet Yusuf’s trials

“I compare myself to a kitten thrown into the sea and told, ‘Swim however you can,’” Asanov’s wife admits. “I’ve learned to both swim and survive. I didn’t even know which side the gas tank was on in the car. Now I can pop open the hood and pour in the oil.”

The family has now been living without Asanov for eight years. The children, Seytmamut and Eskender, began working as teenagers. They took on jobs as kitchen assistants or waiters at a restaurant. “They try hard, they help,” Ayshe says gratefully. “Our eldest son Said went to study to become a dental technician.” Ayshe herself works as a nurse, juggling between her children and her job.

During the trial, Ayshe was able to travel to see him in Rostov-on-Don. But after he was transferred to Mordovia at the end of 2022, the distance became unbearable. The journey felt endless. Within six months, he had been moved to six different colonies. Asanov’s family received his last letter from Rostov-on-Don, as writing is not allowed in the Mordovian prison. Instead, the family calls, and they speak for fifteen minutes a day.

In 2022, Ayshe got permission for a visit, and after a long separation, she and the children went to see Asanov in Colony No. 7 in the village of Sosnovka in the Republic of Mordovia. The journey took three days, changing trains along the way.

When Asanov saw the children, he was overwhelmed. When he was imprisoned, his son Eskender was eleven years old, and by the time they met, he was sixteen. Asanov hugged his children constantly, asking about their interests and what they loved.

I ask how the meeting went. Ayshe quiets. “It was hard,” she admits, her voice breaking.

We sit in silence.

***

“They’re scaring people,” Ayshe says bitterly. “People are now afraid to even go to the mosque to pray. They intimidate them so they won’t attend searches or trials, so they’re too scared to show sympathy for the prisoners.”

Asanov’s father, Refat, adds that these times are no different from what happened in the 20th century: “Nothing has changed; they’re still imprisoning people for nothing.”

In Sosnovka, where Suleyman is now serving his sentence in a penal colony, there once was a GULAG camp. The Dubravny Camp Administration, or Dubravlag. It was in these same Mordovian camps that Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj was once imprisoned, as was one of the co-founders of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, Oleksa Tykhy.

In the colony, Asanov works in a sewing workshop. He believes that one day, this will all come to an end. Prophet Yusuf, whose story is told in the Qur’an, also went through imprisonment. It was one of his trials.

The Cultural-Ethnographic Center Salachyk, created by the Asanov family, was closed by Russian authorities six months after Asanov’s arrest. The courtyard stands empty. The intricately carved gate, opening to a green landscape beneath the cliffs, waits for life to stir there once again.

And for each political prisoner to be able to embrace their child.

This text was written in May–June 2024

Translated by Yevheniia Dubrova

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано світлини із родинного архіву, а також Кримської солідарності.