Thirty three years have passed since the proclamation of Ukrainian independence. Since then, most of its participants have passed away. It means that the history of Ukrainian independence ceases to be a living history. It overgrows with bronze, with inevitable distortions and illusions. One of them claims that Ukrainian independence was gained too easy, without bloodshed or fighting—and that is why now, in the war with Russia, we are fighting for true independence.

To prove it wrong, let’s ask ourselves: what if Ukraine did not gain its independence in 1991?

Communism did not necessarily have to disappear back in 1991. It was quite lifeless but it could last in agony for a long time. Cuba and North Korea are examples of that, and communist China is not only not agonizing, but also keeps developing—although the extent to which it is communist is still questionable.

Finally, communism could fall with the Soviet Union still intact.

In March 1991, Horbachov held a referendum where the people should declare if the Soviet Union should be preserved but in a renewed version, with more rights for its republics. Then, 70% of the Ukrainian SSR population voted for the preservation of the USSR.

Those 30% who voted against, were the inhabitants of the three Halician regions. It is said that Stalin’s decision in 1939 to annex the three Baltic states and western Ukraine was his biggest mistake. If it were not for this decision, the Soviet Union could have lived—as these territories were the main centre of anti-Soviet separatism.

These statements are doubtful, too. The role and potential of these territories were secondary. First, even if they had left the USSR, it would not have ceased to exist because of this. The key territory for the preservation of the USSR was, in fact, Ukraine, even without its western part. Second, since the late 1970s, the Soviet government has been trying to accelerate the russification and sovietization of its western suburbs. This strategy has not been unsuccessful. In the beginning of 1980s, it seemed that even Lviv was becoming a Russian-speaking city.

Western Ukraine was lucky enough to have to endure Soviet rule one generation less than the rest of Ukraine.

So, if the Soviet Union had not collapsed in 1991, but, say, in 2001 or 2011, Western Ukraine could have repeated the fate of the rest of the country, and modern Ukraine would have looked like modern Belarus.

Speaking about Ukraine back then, it looked as an entirely pacified Soviet republic. The opposition was sent to prisons or camps—and the Ukrainian SSR remained the last “oasis of stagnation” until the last years of Horbachov’s reconstruction. Profound changes did not start to unfold in Ukraine until after Scherbytsky’s dismissal in September 1989, but in early 1991, the republic lagged behind not only the Baltic or Caucasian outskirts of the USSR in terms of protest moods, but also Moscow, the imperial center.

As a rule, empires fall apart not from the margins, but from the center. Strong as separatist moods can be on the outskirts, it is decisive for the empire what goes on in the capital. In 1991, Moscow experienced the acute political crisis. Three powers were fighting for power here: Horbachov, who tried to reform the USSR, communist-stalinists, who opposed Horbachov’s reforms, and anti-communist opposition under the leadership of Boris Yeltsin.

On June 12, 1990, the Russian opposition, led by Yeltsin, proclaimed the sovereignty of the Russian SSR. At that moment, Yeltsin was the president of Russia, and Horbachov was the president of the USSR. Yeltsin represented the part of the Russian elite that was dissatisfied with the status of the Russian SSR as part of the USSR. Soviet Russia did not have either its own communist party or the Academy of Sciences, the Russian elite complained about the dominance of the “Khokhol yoke” under Brezhnev, which—citing the diary of one of the then Russian communists, the secretary of the Penza regional committee of the Communist Party, Georgy Myasnikov—was worse than the Mongolian-Tatar, and the common Russians believed that they were living so poorly because “Russia fed the whole world,” including non-Russian Soviet republics.

Advocating for Russia’s status increase, this part of the Russian elite was objectively ruining the empire. It was done not out of their belief that the empire was evil, but out of political convenience. It was not until after the collapse of the USSR, that Yeltsin and his successors began to reassemble the empire in a new way. But in the early 1990s the moods were entirely different.

The Ukrainian communist elite followed in the footsteps of the Russian one. It held a majority in the Verkhovna Rada (the parliament), and a month after the proclamation of the Russian declaration, supported the sovereignty of Soviet Ukraine. It was going with the flow, and although it was clear where the wind was blowing, it was still unclear how far it could take them and whether it would change its direction once again.

As for the non-communist party, many Ukrainians viewed reconstruction as a provocation. They thought it aimed at uncovering as many dissatisfied citizens as possible to arrest or to destroy them later—as it happened after the Ukrainization of the 1920s and Khruschov’s thaw of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Political waters remained deep and turbulent, so, except for the most determined minority among the Ukrainian elite and population—mostly constituted by the dissidents and Western Ukraine,—the majority preferred to swim cautiously and close to the shore.

As Taras Petrynenko was singing, Ukraine was both “left-bancautious” and “right-bancautious.”

If Yeltsin, for the sake of his power, consciously ruined the Union, Horbachov was doing it unconsciously. He had good intentions that pave the road to everybody knows where. Horbachov believed that socialism could have a human face. However, he did not realize that, as Leszek Kołakowski [Polish historian and philosopher — Ed.] wrote, this scull would never smile again. Horbachov lived under illusions. He was a representative of the generation of the 1960s and, like many of his generation, he believed in the historical merits of socialism. He believed that if the power of the KGB and the Communist Party were weakened, the Soviet Union would once again shine in all its glory, whereas, in fact, the USSR existence was ensured by the vertical of these repressive institutions. As soon as Horbachov tried to dismantle them, the system began to fall apart.

The situation in summer 1991 resembled much the one from 1917. Then, after the tsar’s abdication in St. Petersburg, the then capital of the empire, two centers of power appeared—The Provisional Government and the Council (Soviet) of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. The conditions of 1991 in Moscow were further complicated by the fact that, apart from two official authorities—Horbachov and Yeltsin—there was the third one, too, the unofficial power of the old communist apparatus, which wanted to return the USSR to the pre-reconstruction days. On August 19, this third authority tried to organize a coup.

Its collapse proved that not only the skull of communism could no longer smile, but it was also entirely toothless.

In Moscow, the person who used this collapse most was Yeltsin. In contrast to the weak-willed Horbachov, he led the resistance to the GKChP and proved to be the master of the situation. While outside Moscow Ukraine was the one who used the situation in its favour, proclaiming its independence on August 24. The GKChP collapse explains why the Ukrainian people so rapidly changed their views by 180 degrees. It was no longer cautious, as there was no one to guard against.

The other key circumstance was that in summer 1991 Ukraine saw a situational union of three unlikely allies: mostly Ukrainian national democrats, but not only from Western Ukraine; national communists led by Leonid Kravchuk in Kyiv; and the miners’ strike movement in Donbas. Each of these three powers had its own reasons to lead Ukraine out of the USSR. Each of them separately was in the minority, but together they were the majority.

In this situation, the idea of Ihor Yukhnovsky, the then head of opposition in the Verkhovna Rada, to hold an additional referendum in December was brilliant. If Ukrainian independence had been proclaimed solely by the Ukrainian parliament, its genuineness would have been questionable—as the memory of the March referendum was still fresh.

It is known from the unpublished memoirs of Ihor Yukhnovsky, that his idea of the referendum was a spontaneous one. But this spontaneity eventually turned into a new solid reality. It legitimized Ukrainian independence in the eyes of the world. It is worth mentioning that both Margaret Thatcher and George W. Bush during their speeches in the Verkhovna Rada made it clear they supported Horbachov, the savior of the empire, not those Ukrainians who wanted to destroy it.

It basically refutes the statement that independent Ukraine appeared with the support of the West; in fact, the Ukrainians achieved it on their own—not thanks to, but despite the will of the big players.

Zbigniew Brzeziński called the proclamation of Ukrainian independence to be one of the most important events in the history of the XX century. In hindsight, however, it can be observed how great historical events depend on accidents and trifles. Ukrainian independence of 1991 did not fall from the sky. It was the result of the specific actions of many people who used every circumstance to achieve a great goal—just like climbers who cling to every rock ledge on their way to the top.

It does not diminish the meaning of Ukrainian independence. On the contrary, it shows that favorable historical tendencies are complicated and fragile. That’s why it is vital to fight for them, stand for them until they solidify and become as hard as a rock.

Yaroslav Hrytsak, historian, professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University

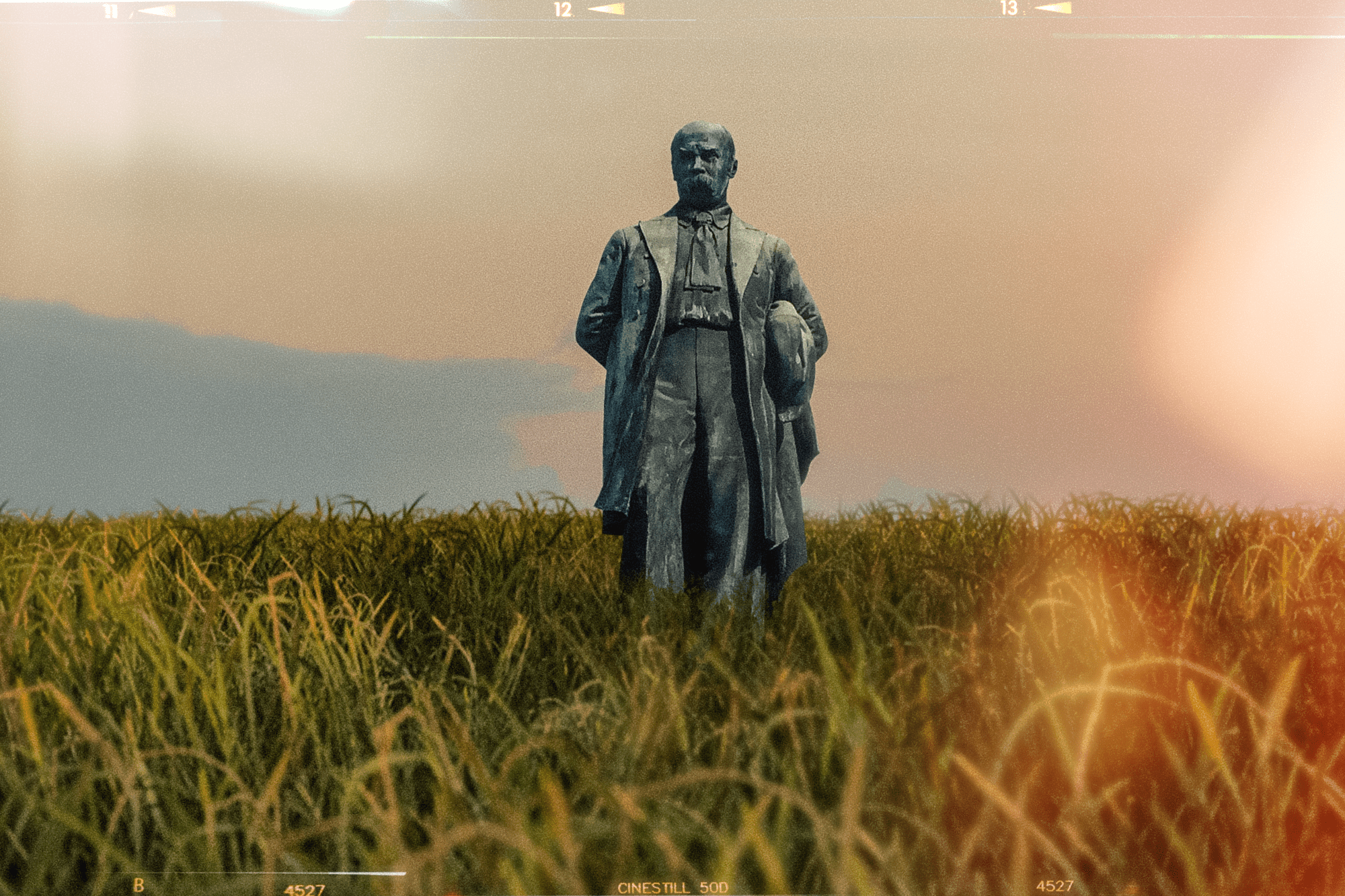

Illustartion — Vadym Blonskyi

Translation — Olha Dubnevych

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]