Each year, on the second Saturday of September, we celebrate Ukrainian Cinema Day—the cinema for which Sergei Parajanov was imprisoned and Alexander Dovzhenko rewrote his scripts to appease Soviet censors. The cinema that won an Oscar for documenting Russian crimes in Mariupol so the world can no longer turn a blind eye.

We spoke with three Ukrainian directors about how our cinema evolved under Soviet censorship, whether artistic traditions can survive when the continuity of generations is repeatedly disrupted by Russia, how to cultivate a desire to watch Ukrainian cinema in a domestic audience, and whether making narrative films is possible during a full-scale war.

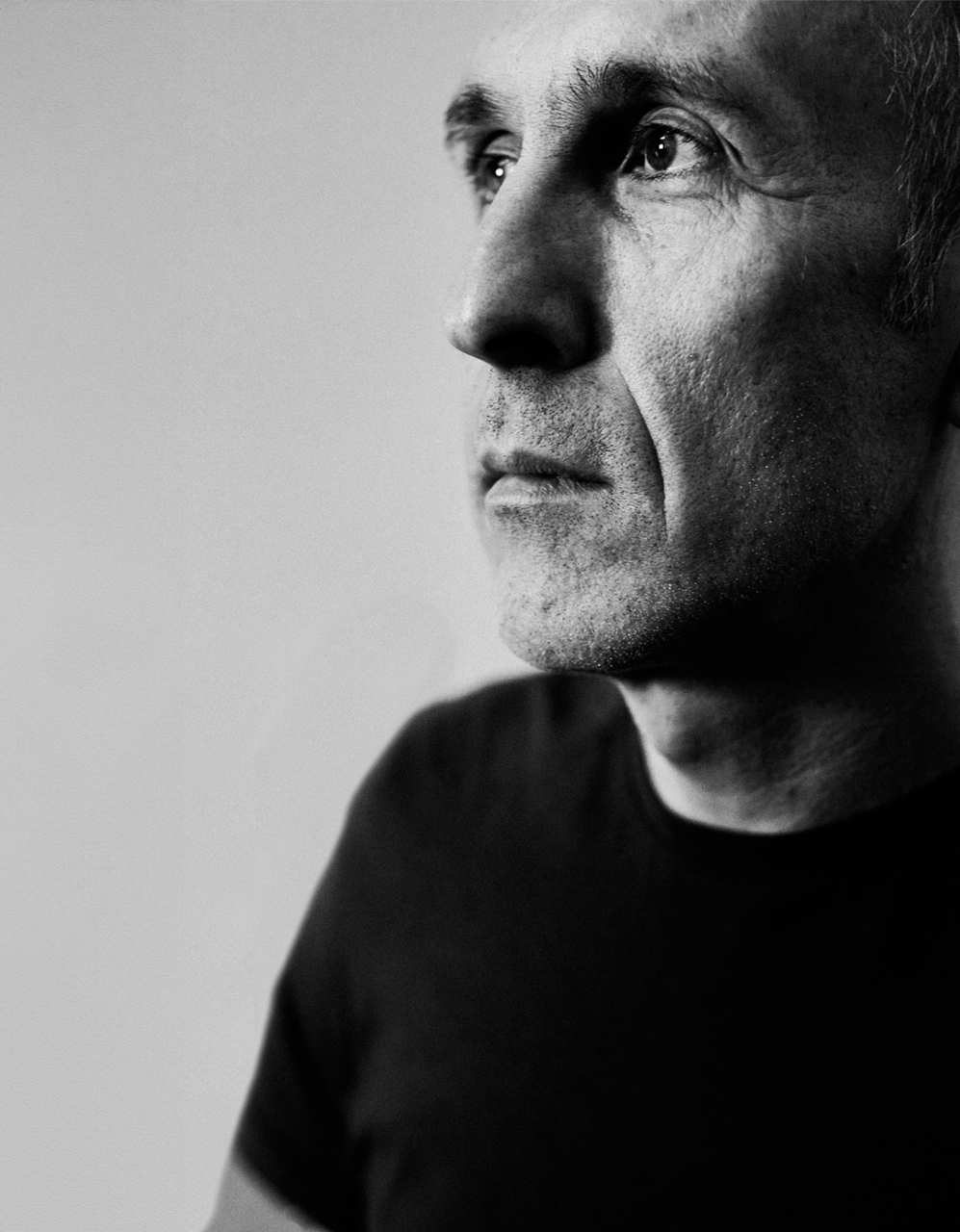

Volodymyr Tykhyi, director, screenwriter, producer. Co-author of Assholes. Arabesques, Ukraine Goodbye! projects and Babylon’13, and creator of the film Independence Day.

“My first experience with Ukrainian cinema was Parajanov. I grew up in western Ukraine, near the Polish border. At that time, Parajanov was in prison, but Polish TV—critical of its own government—aired Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors at night with a preface. They didn’t dub it, only subtitled it. It was like a mystical revelation; suddenly, I saw that there was cinema about Ukraine and it was amazing. I hadn’t seen anything like it before. I was about 11 or 12. Now I understand that it was a gesture of solidarity from Polish TV—a solidarity with the persecuted Parajanov and, perhaps, with Ukraine.

We’re now building a new cultural context. Not a new one, really, but a true, authentic, Ukrainian context—not totalitarian or post-totalitarian. Names like Dovzhenko and Parajanov gain new significance and understanding. What they created were sincere works, valuable documents of their times.

Now, though, a film like La Palisiada by Philip Sotnychenko will tell us more than the entire creative output of the Dovzhenko studio in the ’60s and ’70s because times have changed. You can’t watch ten Ukrainian films and think you’ve grasped our cinema. That was possible 30 years ago when every reel was an event.

Today, digital technologies have allowed us to recreate the past using AI. Within a decade, we’ll be able to reconstruct historical events based on documentary materials. Unfortunately, in Ukraine, we currently face a crisis in technological production—it simply doesn’t exist. Previously, it was stabilized by the state’s somewhat reliable funding. There was some sense of self-exploration in our cinema, but that’s been lost now. If you look at what happens when these processes work, you see examples like Poland, which has its own Polish Netflix showcasing high-quality local productions for a Polish audience. We’re working on restoring that continuity.

At the same time, we’re part of the global context. Our documentaries are extremely important abroad. Even without festival success, they’re noticed. Our documentary cinema will be referenced in creating the next James Bond. Perhaps this isn’t the agency we’d dreamed of, but it’s something.

We need to be persistent. To hold onto the memory of everything we’ve lost. Quality always wins out and leads to greater scale, so it’s worth creating high-quality cultural projects that contribute to new contexts—contexts that we really need and that will eventually grow into something popular for audiences, representing us internationally.

Of course, creating during wartime is traumatic. Directors, cinematographers, actors—everyone relies on models developed in Europe and America. But Ukraine is a land of constant instability, and we need to recognize that what’s happening to us is unique, not routine. Even having major successes, your peers elsewhere are doing completely different, routine work. In our case, we always have a chance to win an Oscar because we’re documenting history, like Chernov and his 20 Days in Mariupol.

For now, narrative cinema isn’t really feasible in Ukraine. Globally, there’s a crisis in narrative cinema. Thirty to forty years ago, creative risk was essential to success. Now, it’s practically absent. Real cinema thrives on a certain rebellion—social or cultural. That’s why we keep turning to documentaries, where you can’t ignore reality like you can in fiction. It pushes you toward experimentation. Classic WWII films are irrelevant in the context of modern-day Ukraine.

We make cinema with what we have on hand. At Babylon’13, we’re operating on a very low budget, so there’s a constant influx of new talent. Right now, we have many women working with us, as almost all the men have been mobilized. From these constant changes and unstable conditions, we draw new approaches.”

§§§

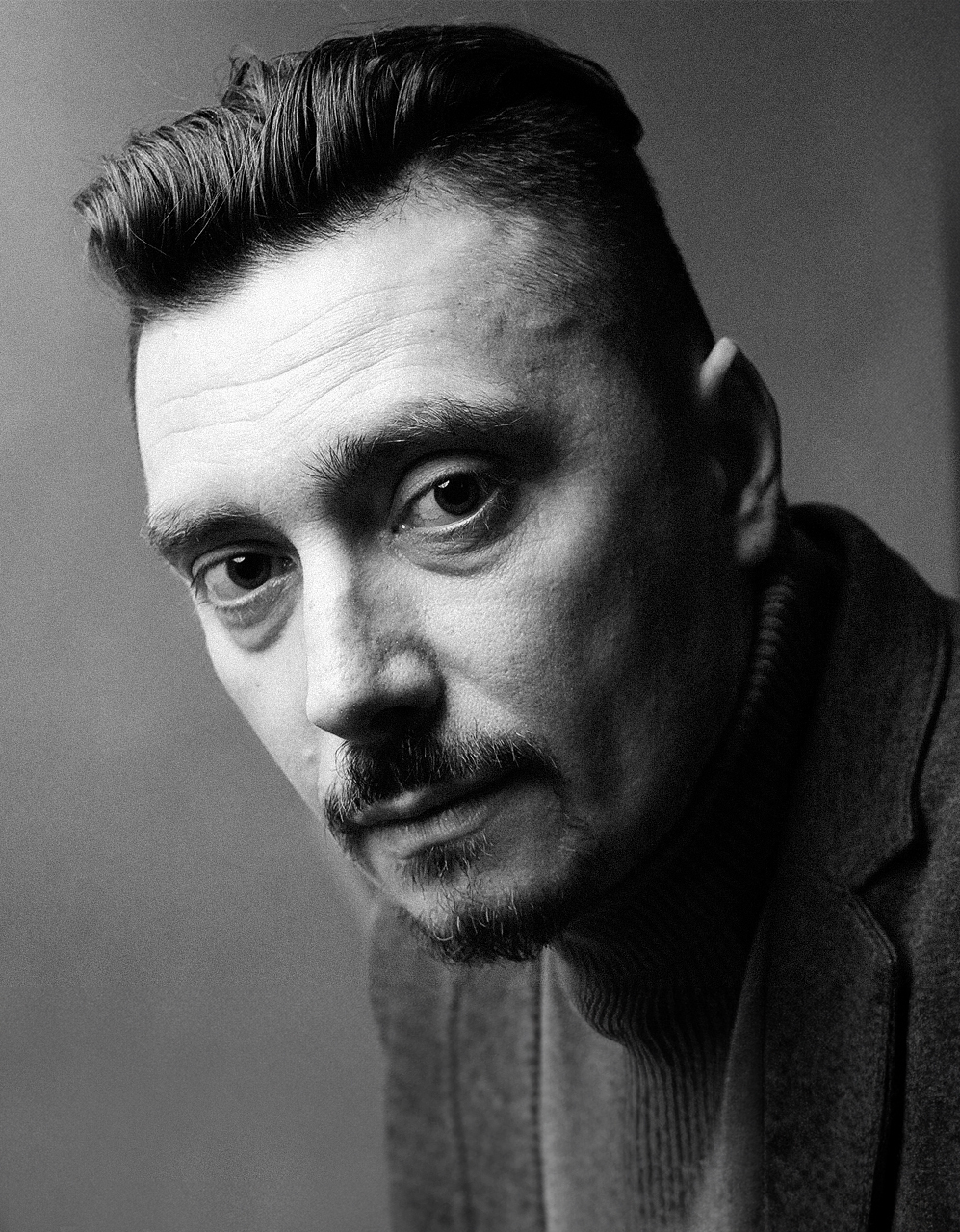

Dmytro Sukholytkyi-Sobchuk, director and screenwriter, creator of the Pamfir film.

“I’m 41, a little older than our country. I caught echoes of socialist-realist ideology; Lenin’s portrait was on my ABC book. At 8 or 9, I heard my parents’ stories of how my great-grandmother was imprisoned for trying to gather ears of wheat from a field. At 8, I proudly wore a trident pin instead of the Little Octobrists star [a youth organization for elementary school children in the Soviet Union – T/n]. These were my first realizations of who I was and where I lived.

In school, we were taken to American films. When I had evening classes, I’d watch Ukrainian films on TV, which only aired during the day. That’s when I first realized that movies could be about us and our lives, not just cowboys and distant worlds. Then, Soviet classics took over. I still think that we should show those simple Soviet comedies to children to explain agitprop—how they portray various nationalities: Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, Wedding in Malinovka, Oleksa Dovbush (1960), etc. These films should be watched with directors and film critics who can explain why and how they were made.

Ukrainian cinema often ended up on the shelf, censored. The film studio director was appointed from Moscow. A Soviet filmmaker could only make films on three themes: virgin land reclamation, collective farms, and WWII. Every creator faced harsh censorship. We remember Askoldov, who made one film, Commissar, before being thrown out of the profession by the Soviet government. Take a look at The Long Farewell by Kira Muratova—it subtly mocks Soviet conventions. A handful of Ukrainian filmmakers could establish themselves as notable figures: Kira Muratova, Yurii Ilienko, Roman Balaian.

With the digital revolution making filmmaking accessible to all, it became clear that we could enter the European context through emerging filmmakers doing something radically new, awaiting their next works to see mature artistic expression on various topics with deep insights.

Today, it seems to me, we have far more diverse choices than even a decade ago. Roma Bondarchuk, Kateryna Hornostai, Philip Sotnychenko—now just take a seat in the theater and watch who among us, the first generation of filmmakers like this, will become these new authors.”

§§§

Marysia Nikitiuk, screenwriter and director. Worked on the Ukraine Goodbye! project and the films When the Trees Fall and Lucky Girl (Я, Ніна)

“My journey into cinema started in 2012 with the Ukraine Goodbye! lab, where we screenwriters and playwrights spent a year working on the Ukrainian Short Film Anthology, dedicated to Ukrainian emigration. It was a true lab, made possible in 2011 when the Ukrainian State Film Agency was relaunched and started operating independently of the Ministry of Culture, following a European model with support for national film projects. It’s a popular European practice, so it was a great example of not reinventing the wheel but using a system that works. Ukraine doesn’t fit, for example, the American or Indian model, where the domestic market is huge. Ours is small, almost nonexistent, and people aren’t accustomed to watching films. So, our filmmakers work similarly to those in Europe—the national film fund protects domestic producers who create their own narratives.

Since 2011, we’ve had strong support for debuts, both short and feature-length. It was more a matter of non-intervention than direct support, and that was a good thing. Writing films, finding funding—it’s all a lengthy process, at least three years. Once you launch production, stopping it is incredibly costly. Our films started making it to top-tier festivals, creating a continuous process. This was a major breakthrough after everything Ukrainian cinema went through in the ’90s.

In Tonia Noiabrova’s charming film Do You Love Me?, she reflects on that time. The protagonist’s father lost his job at the Dovzhenko studio when Ukraine gained independence. We went from a Soviet system to an ostensibly free market. But the film market as such did not, and no one was working on cultural policy. So almost no films were made. I remember going to cinemas with my parents only to find underwear and Belarusian textile exhibitions because theaters rented out space to survive. It’s funny but also a massive cultural catastrophe that happens to us periodically.

But the thing is that if we don’t tell our stories, others will.

Horrific Russian films like Taras Bulba, which is both laughable and painful to watch, are a testament to that. And that doesn’t even include the Russian depiction of Ukrainians—miserly, crude, clumsy—stereotypes from KGB jokes about other nationalities. If we don’t address our own narratives, others will fill that empty space with often hostile perspectives.

In reviews of my films, Europeans write that I am a successor to Zvyagintsev’s tradition. That’s how comparative analysis works: you search for comparisons, and you match with what you know—Russians, Polish cinema, Romanian New Wave—due to similarities in architecture and visual style. But my inspirations were Cassavetes, Béla Tarr, von Trier, Miyazaki. At the same time, we do have common ground with the Romanians and Poles, who started reflecting on the post-Soviet context and totalitarian regimes before us. We share similar stories, similar fates, and we all, in one way or another, suffered from Russian influence. For instance, Romanian directors are fully on our side—they have no doubts about who’s right in this war because they understand us.

Right now, we’re in a catastrophic moment: just as Ukrainian cinema was emerging and beginning to earn international accolades and markets, it’s facing new challenges due to this full-scale war. And here we are again, grappling with the question of what to do with this cinema. So, such things emerge, like a Russia Today propagandist’s film about “good Russians that are forced to kill Ukrainians, and suffer greatly because of it” that ended up at the Venice Film Festival. Meanwhile, Kirill Serebrennikov remains a charming ambassador of the imagined “beautiful Russia of the future”, premiering a film about fascist Limonov in Cannes. Meanwhile, we aren’t doing anything institutionally for cinema or arts policy, and any low-quality productions get ignored by Western film communities.

We’re losing continuity. As soon as the empire weakens its grip, flowers bloom. Then they try to destroy us again, breaking any progress we’ve made, leaving us to start creating culture as if from scratch (though it’s not really true). The Russians’ trajectory has been consistent since Ivan the Terrible; for us, it’s repeatedly interrupted and forgotten. We either blend in or rebel. The aggressor has been on a set trajectory for centuries, like the Chinese empire, but our resistance is always new. Mentally, our art is steeped in vitality. For Russians, it’s an unbroken chain of coercion and “die for the motherland”; for us, it’s “heroes don’t die”. Of course, they do, and we mourn them. But these codes are crucial, woven into our culture.

We like watching foreign films because they feel like a fairy tale to us. When we see films about ourselves, it hurts, and we turn away. It will take a long time for our audience to be able to look critically at itself in film. But just as we start to mature, they begin destroying us again, and it all starts over. Vakulenko, Amelina, Nika from Kharkiv.

All of us who have something to say—we’re already counted by them, the Russians.

Without this tragedy, we’d already have a fully competitive, healthy market, albeit a small one. We’d have students of Dovzhenko, and we’d be keeping Khvyliovyi’s autographs at home. Yesterday, a friend showed me a script by Parajanov with his drawings, found by chance. It’s an absolutely priceless artifact, yet today, it’s underappreciated here, and that’s a huge problem for us.

Now, as we try to fill in these blank spaces, we’re rediscovering Khvyliovyi and Yanovskyi, building bridges to our past. But there’s no energy left for contemporary writers and cinema. So, we escape into illusions like “Marvel” with its superheroes, even though we know it’s not our story at all. All those Batmans and Supermans would a hundred percent shit their pants on the front lines.

Translation — Iryna Chalapchii

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]