“I’ve never been to Tarkhankut, even though it was only 30 kilometers away. I always thought I’d have time… but it wasn’t meant to be, and who knows when I’ll be able to go,” my friend Seyran, a fellow Crimean I met in Kyiv after the peninsula’s occupation, tells me.

“And I always wanted to take a boat from Sudak to Yalta, though I’d tell others it was just a tourist attraction to milk more money out of them,” I share with Seyran.

For those of us bound by blood and spirit to Crimea but physically separated from it now, questions emerge from time to time, questions like “What didn’t I manage to do before 2014?” as we assumed we’d always have the chance.

History doesn’t care for hypotheticals, but when I’m alone on the pedestrian bridge to Trukhaniv Island, watching the Dnipro’s current in the cold sunset, I start thinking in “what ifs” and “woulds.”

Who and where would I be without the occupation? How would I have built my career and personal life? Who would I have talked to and visited?

Perhaps my incredibly wise and sophisticated friend Nariman Dzhelyal could have become the rector of a Crimean Tatar university, a prominent TV host of public affairs programs, or the prime minister of the Crimean government. Instead, he became the leading voice for Crimea’s free people as First Deputy Head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People.

Since 2021, Nariman has been imprisoned in Russian jails, 6,000 kilometers from his wife and children, accused by the Russian regime of absurd charges over a gas pipeline explosion in the Simferopol district. He has been sentenced to 17 years behind bars.

Or my always cordial friend Server Mustafayev, who could have had a thriving confectionery business and written poetry for pleasure, but instead became a human rights advocate and citizen journalist with the “Crimean Solidarity” initiative. In 2020, Russia’s punitive machine sentenced him to 14 years in a high-security prison for his alleged “participation in a terrorist organization.”

By the way, Russia brands the absolute majority of the Crimean Tatar political prisoners as terrorists or extremists, attempting to make Crimean Tatars appear as dangerous radicals.

But one undeniable fact remains: before Russia’s occupation, there were no terrorist acts in Crimea. Since then, the terrorist nation has turned the peninsula into its main hostage.

Take Iryna Danilovych, for instance, who could have led reform efforts in Crimean healthcare. Instead, she became a blogger and human rights advocate, for which Russia imprisoned her in 2022 with a seven-year sentence, supposedly for finding an explosive device in her bag.

Occupation never leaves positive outcomes for those who seek to improve their land and live by the ideals of dignity and freedom. Occupation leaves countless scars—both physical and mental.

One of these traumas is the trauma of separation, in which, over ten years, not only have people been forcibly uprooted from Crimea and scattered across the world, but they have also been made to live in conflicting realities.

For ten years, Russia has poured effort into colonizing the peninsula, transforming its inhabitants into “little Russian citizens” in both mindset and behavior. Meanwhile, Crimean exiles in other parts of Ukraine have become a passionate part of society, helping to build a national Ukrainian political identity.

In addition, Russia has resettled nearly 800,000 Russians in Crimea, once again shifting the peninsula’s ethnic and religious makeup. Ten years in, the average Crimean has adjusted to life under occupation and isolation, moving past the initial “waiting mode” in which they lived during the first few years. An average Crimean now adapts to their circumstances, where survival and safety are the core drivers.

Yet, among the Crimean Tatars and pro-Ukrainian residents of Crimea, there have always been people like Nariman, Server, and Iryna, people who have always taken on greater responsibility—not only for their families but for a peninsula with a Ukrainian spirit, serving as nerve connections between those under occupation, those in free Ukrainian territories, and those in forced migration.

Healing the trauma of separation requires collective reflection and action focused on the future by asking questions like, “What will Crimea be like post-deoccupation, and who will I be in such a Crimea?”

Here, the Ukrainian state and civil society must deliver clear messages to people in occupied territories about transitional justice (what will happen to property, how Ukrainian laws will be reinstated, and who will be deemed collaborators), the legal status of the peninsula (why Crimean Tatar autonomy is not about danger of separatism, but about restoring the collective rights of the indigenous people, enhancing their agency, and preserving their identity), and the re-establishment of Crimea’s native names through a decolonization process for the peninsula’s titles and events.

At the same time, these solutions must be communicated to the entire Ukrainian society, so that Crimea doesn’t remain a “souvenir” in people’s minds, and Crimean Tatars aren’t perceived as outside factors.

In my humble opinion, part of the answer lies in building bridges of trust with the new generation—those whose childhood began in 2014.

Today, this generation on either side of the front line grows up in antagonistic contexts and with different heroes. In Kyiv, my friends’ children walk to school on streets named after the Heavenly Hundred and fallen soldiers of this war. Whenever they see people in military fatigues, they run up to thank them, and when they hear an air raid, they silently take a mat, sit between two walls, and wait for enemy planes to land.

Meanwhile, my Crimean friends’ children are visited by Russian soldiers in school, who share stories about “heroes of the Special Military Operation defending against Banderites.” These kids are forced to write “letters to the front” and sing the Russian anthem at assemblies, while their textbooks present a distorted history of Crimea and portray Crimean Tatars as a “nation of traitors.”

Some parents are now reverting to Soviet-era practices, arranging private or home lessons for their children on the Crimean Tatar language or history. So, we must create an ecosystem for Gen-Z that provides access to knowledge and opportunities, fosters critical thinking, and preserves both national and political identities, so they can understand why it’s worth choosing democracy and an open society over an authoritarian, human-hating regime.

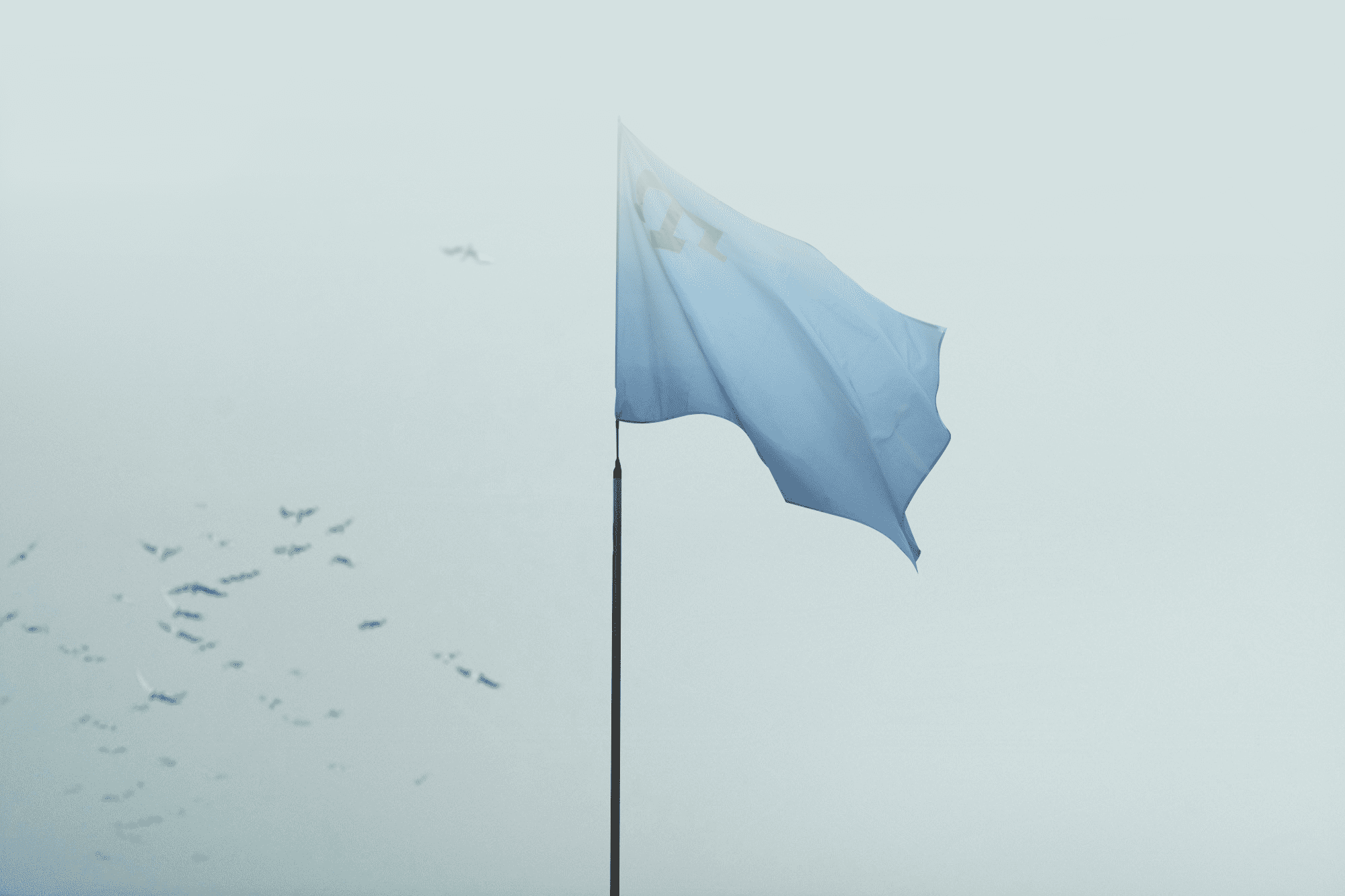

Our critical, but inconspicuous task is to shift our own paradigm from “ours vs. other” to “ours vs. our other”: to support families of political prisoners as our own, provide momentum for the development of representative institutions, language, and culture of our indigenous people, study Crimea’s history as a vital part of Ukraine’s, and never, ever allow ourselves to believe in the “eternity” of Crimea’s occupation. Because however long temporary feels, after it, the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar flags will wave over Demirci yayla once more.

Alim Aliev — human rights defender, Deputy Director of the Ukrainian Institute

Illustration —Vadym Blonskyi

Translation — Iryna Chalapchii

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]