Reflecting on the changes of the past decade, we asked writers to share how their cities have transformed. Nadiia Sukhorukova remembers Mariupol, remembers in the way her memory preserved it.

When I return to my city, everything will be different, and I won’t recognize it. At first, the Russians were ravaging Mariupol with rockets and killing with bombs, then they took it captive, and now they torture it with lies and hatred every day. The city I was used to no longer exists. But we are here—its residents. And from thousands of memories and hopes, we can rebuild it anew. First, we just must drive out the occupiers; until then, we must keep those memories alive within us.

***

I am five, swimming in the Sea of Azov. I pretend I don’t hear or see my mom, who is shouting from the shore: “Nadiia-a-a!” and waving her hand.

I don’t want to get out of the water. I know she’ll say, “You’ve been in the water for half an hour! Your lips are blue! Stay on the shore until your undies dry.” But I don’t see the point in going “to the sea” if you’re sitting on the shore.

Since then, I remember how huge the city seemed, how the sea seemed the warmest, the apricots in my grandmother’s garden—the tastiest.

Now I’m 10, returning from music school. It’s cold outside—November sure is cold in Mariupol. Ice pellets fall from the sky, scratching my face. For some reason, I’m angry not at the weather but at the city. Why is the autumn wind so biting, and why do the trolleybuses come so rarely?!

I’m 16, and I’m in love for the first time. My prince is named Myshko, and the feeling is mutual. My face shines as if the sun passes through it. Mariupol shines along with me. Myshko and I hold hands as we walk the streets of the old city. It’s spring in Mariupol, and the city seems as happy as we are. It gently caresses our cheeks with warm wind. Have you seen how beautiful Mariupol is in April?!

In a few years, I’ll feel cramped here and leave. When I return, Mariupol will seem surprisingly small and unremarkable. I’ll have to get used to it again and tell my friends from big cities, “Here, time is stagnant. Everything is stable and gray”. It will hear me but won’t be offended because I’m not a stranger. It has known me for many years, since my birth. It’s used to my quirks. It will be opening up to me again, like a flower after the rain, and I will fall in love again with its streets and parks. I will only realize there’s no better city for me when I lose it.

***

We are hiding from death in mid-March. The specific date remains in the basement of our nine-story building. I scratched it into the wall with my apartment keys “03/16/22.”

I still can’t explain why I did this. So pointless and childish. I just thought we would never escape the city that had become a trap for us. I wanted something of mine to remain—even if it was this silly inscription on the wall.

We are leaving the city that no longer exists. I count down from ten to zero in my mind to calm myself and not weep out loud. I whisper the numbers silently. My memory captures everything I see, as if an old camera shutter clicks in my head.

Ten. The basement, where it’s hellishly cold and terrifyingly silent.

Nine. My childhood yard—an entire stairwell of apartments burned down in the neighboring building.

Eight. The parking lot in Svobody Square [Ukrainian for “Freedom” Square — Ed.] and dead people on the ground.

Seven. A building on Myru Avenue [Ukrainian for “Peace” Avenue — Ed.] torn apart by shells, where a friend of mine lived.

Six. A massive crater from a bomb dropped by a Russian pilot on the hospital.

Five. The road, where electrical wires and blue-and-yellow flags lay fallen, intertwined like snakes.

Four. People shuffling by, like the living dead.

Three. Roofs of buildings sliced by shells and a tree uprooted.

Two. A car with “Children” written on it, shot up and burned on the corner of the street.

One. Blackened tanks sprawled at the city’s exit, like dead animals.

Zero. Houses and streets blackened with horror—wherever you look.

Mariupol—a black abyss of grief, my dearest city in the world.

***

I always explode when people talk about it with disdain: “They spoke Russian there,” “Many awaited this,” “It’s their own fault.”

That’s a lie. Mariupol was a strong, fearless, and free Ukrainian city. So free that hundreds of nationalities coexisted under one sky. Until ten years ago, when admirers of the “Russian world” arrived. They claimed to be “saving their own.” I remember a woman standing fearlessly against a crowd of excited people ready to fight, gathered on the city council stairs, smashing windows to get inside. She looked a man with a bat in the eye and said, “Your people aren’t here! This is a Ukrainian city!”

Then fear and chaos settled in the city. Armed people barricaded the city center with ugly sandbags, displayed weapons in windows, and began robbing stores and ATMs. They were quickly driven out, but they hid close by—just a few dozen kilometers away. A year later, they invaded again, leveling down several villages nearby, turning them into a gray zone.

We didn’t know then that turning living cities into scorched earth was their usual practice. But we were already resisting the invasion.

I remember Maria Podybailo and her son Danylo. They taught me not to be afraid. Ten years ago, I heard Danylo sing “Synio-zhovta balaklava” [Ukrainian for “Blue-and-Yellow Balaclava” — Ed.]—a song about Maidan, freedom, and the willingness to give one’s life for the country. The boy sang, and his mother, Maria, admired him. In early summer 2014, Mariupol was occupied, but at the graduation ceremony, Danylo and his classmates held blue-and-yellow flags. Along with other Mariupol residents, they took part in Ukrainian rallies and sang the anthem as Russian tanks brazenly advanced on the city.

Thousands of people stood in the square to tell the world that Mariupol is Ukraine while the city rumbled with fighting. Then they all marched to the eastern outskirts and formed a human chain to support Ukrainian soldiers—unarmed people in embroidered shirts.

In 2022, Danylo Podybailo found himself in besieged Mariupol. He survived and saved his family, and shortly after, he went to the front lines. He died on June 1, 2023, near Bakhmut. A poet, musician, soldier in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, an aerial reconnaissance operator from Mariupol—a hero of Ukraine. I want one of the streets in Mariupol to bear his name—Danylo Podybailo Street.

***

For all 10 years, Mariupol felt the breath of war. It was such a close neighbor that people learned to live alongside it. They taught this to their children.

A few years before the full-scale invasion, I met Kateryna Sukhomlinova and her daughter Yeva. Kateryna organized a club for local children. They gathered in an ordinary nine-story building on Marine Boulevard, in a room called “Svitlytsia” [Well-lit and cozy room in Ukrainian homes, often used as a living or guest room, symbolizing warmth and hospitality — Ed.]. Kateryna taught the children to understand their country and also to survive in critical conditions and help others. The kids learned first aid, and I watched skeptically, sure that teenagers would never need such knowledge.

I believed our city was invincible.

Life showed me I was wrong.

During the siege of Mariupol, when bombs fell from the sky so often that it was impossible to reach a parallel street, let alone a hospital, the children from “Svitlytsia” sometimes were the only ones who could help the wounded.

Kateryna taught me to see deeper, not to take things at face value, and to rely on my strengths. She did everything: from huge pots of borscht for our soldiers to first aid courses for schoolchildren. In 2022, Kateryna helped Mariupol residents survive—under shelling, she delivered food and water to elderly and lonely citizens.

Then, Morskyi Boulevard [Ukrainian for “Marine” Boulevard — Ed.], which smelled of happiness and the sea, was turned into ruins by Russian bombs and shells. Kateryna left Mariupol to save her daughter Yeva.

***

Four years ago, in 2020, I prepared a reportage about the patrol police in Mariupol. We were in the car of Chief Mykhailo Vershynin when suddenly a car caught fire ahead. Vershynin stopped the vehicle and rushed to help. It happened so unexpectedly that my colleague and I didn’t even have time to film it. I wondered, “Would he have acted the same way if we weren’t there?”

Mykhailo Vershynin, call sign “Kit” [Ukrainian for “Cat” — Ed.]—a tall, kind, childlike man and one of the defenders of Donetsk Airport. Sometimes I would argue with him. Not all Mariupol residents got along with his patrol officers. Complained they weren’t polite enough. He would explain, provide arguments, and read my angry social media posts. In March and April 2022, Mykhailo Vershynin and his “not always polite” patrol officers continued to help the people of Mariupol. They were the first to clear rubble, help put out fires with rescue teams. As long as there was fuel, they delivered food to basements where women and children were hiding and brought medicine to the sick and people with disabilities.

When the Russians bombed the maternity hospital, Mykhailo Vershynin arrived at the scene and helped rescue people alongside the military. My colleague and friend Natalia Diedova saw him there; she said he appeared solid as a rock — reliable, strong, unshakable.

Mykhailo Vershynin, call sign “Kit,” taught me not to give up and to keep doing what I have to, even when it’s deadly dangerous.

When street battles made it impossible to move around the city, he reached “Azovstal” and, alongside Ukrainian soldiers, continued to resist the Russian occupiers. Then came a long captivity and his return to Ukraine. He was exchanged, and he survived. But I didn’t recognize him in the group photo of exhausted, worn-out people. Half of that rock was gone. Even his eyes had changed. But he still smiled.

***

A fellow Mariupol resident recently said that with each passing day, the hope of returning grows smaller, while the fear of seeing the city as a completely unfamiliar and foreign place grows bigger. After two years apart, Mariupol feels so distant that reaching it seems like it would take a lifetime; and maybe even a lifetime wouldn’t be enough.

We still don’t know exactly how many people died there. It’s likely tens of thousands of city residents. Those who survived and managed to escape have scattered worldwide. Their voices can be heard from everywhere, united by a common desire—they want to come home.

One day, I received a message from a woman who remained in Mariupol. She couldn’t leave the occupation, and for two years, she too has wanted to come home. To the Ukrainian city Mariupol was before the Russian invasion. She sent me a photo of a small Ukrainian flag standing on her windowsill behind the curtain, with the caption: “Ready to meet!” The blue and yellow piece of fabric peeks out from a surviving window, facing a street where hardly any buildings remain. That’s why I believe that when we return to Mariupol, there will be someone to welcome us.

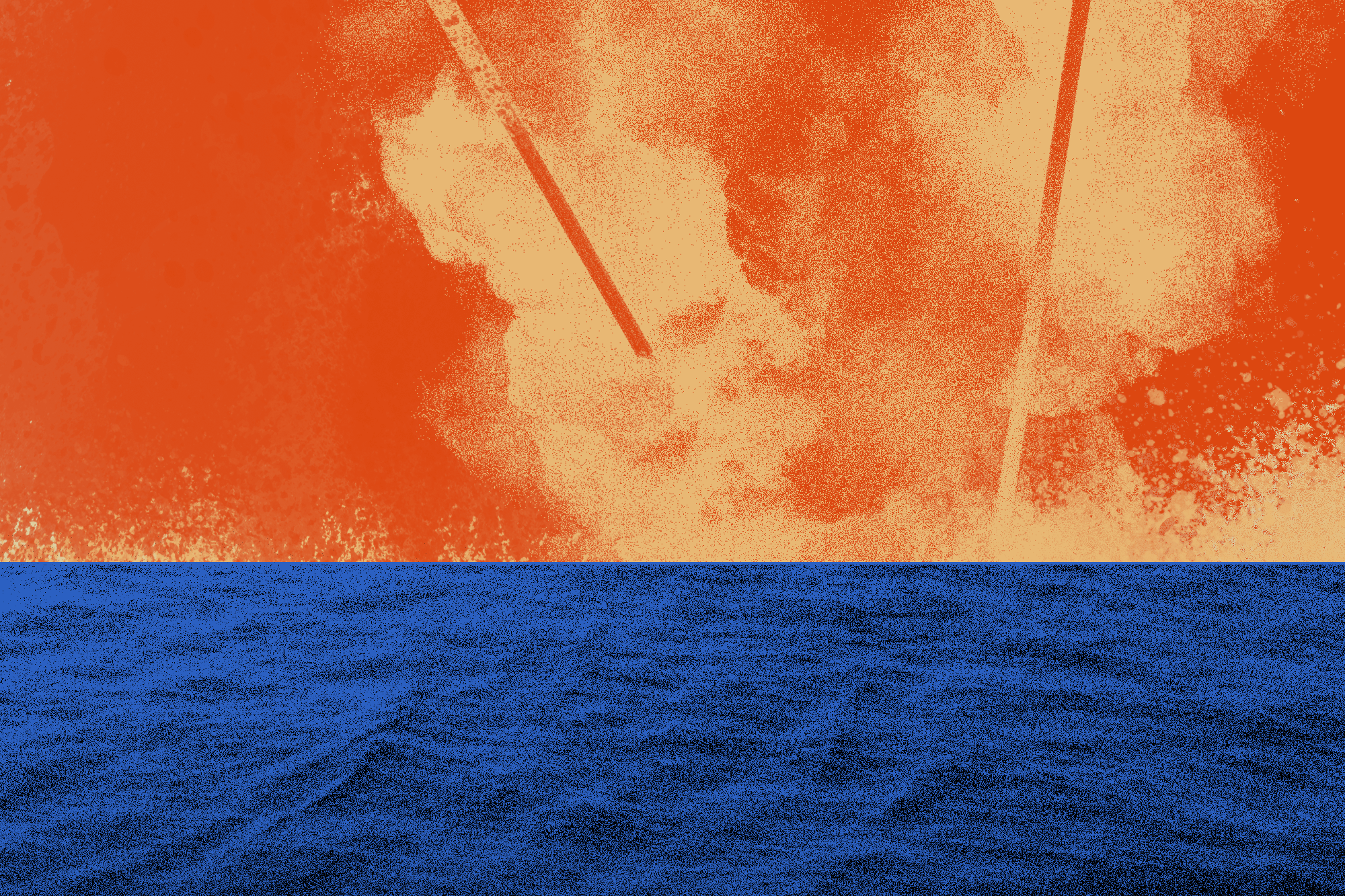

Illustration — Vadym Blonskyi

Translation — Iryna Chalapchii

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]