This excerpt is from “The Train Arrives on Schedule,” a book by Marichka Paplauskaite, the editor-in-chief of Reporters magazine, published by Laboratoria Publishing House. The author traveled over 8,000 kilometers and conducted more than 40 interviews with railway workers, including conductors, station attendants, drivers, station managers, and top executives of Ukraine’s largest company. Her goal was to understand how the Ukrainian railroad became a symbol of resistance in Russia’s war against Ukraine. The chapter presented here reveals the details of international special operations, illustrating how the railway is transforming itself and the nation.

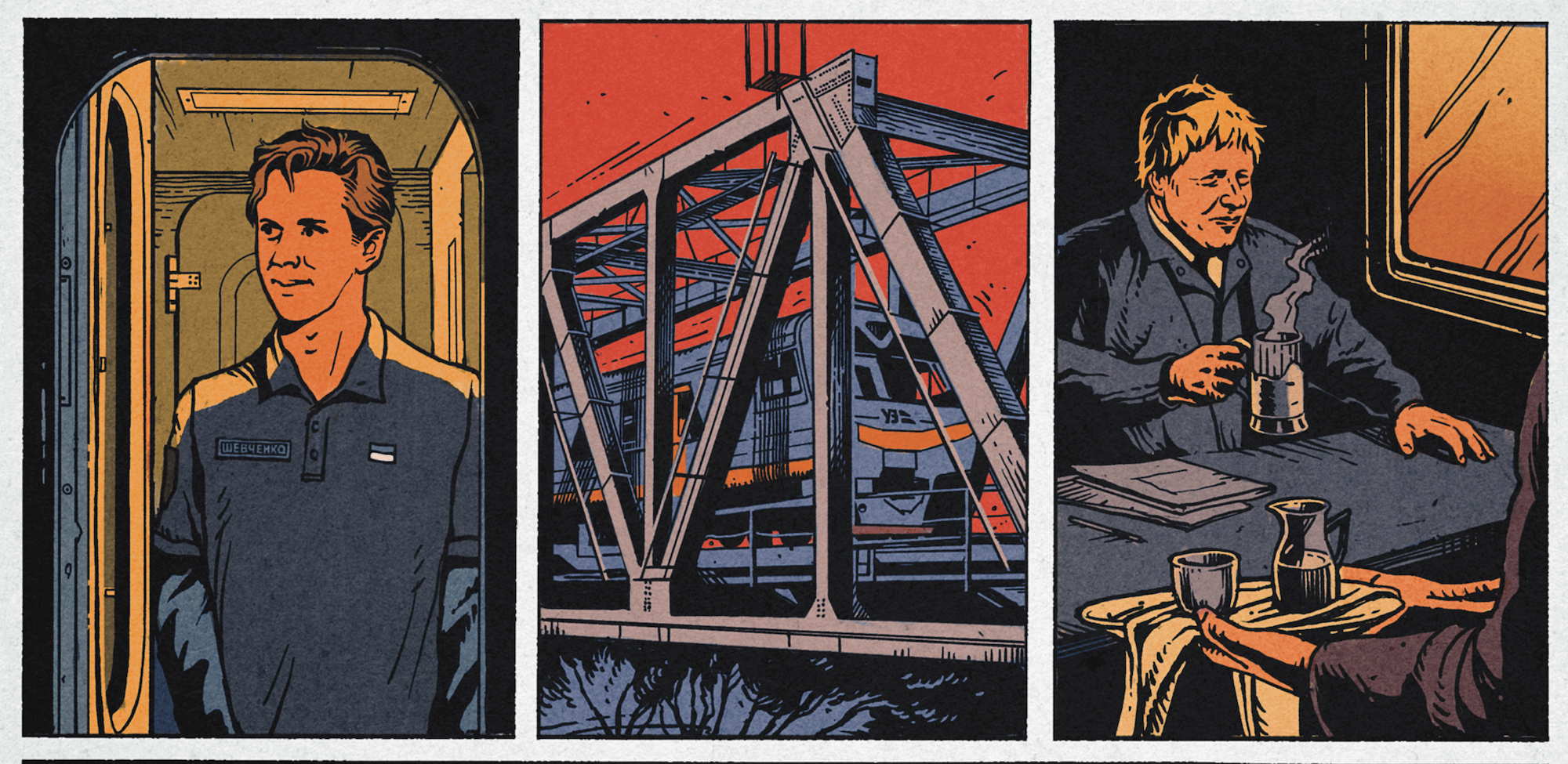

A man, easily recognizable yet disguised as an ordinary passenger.

It’s six in the morning, and a high-speed train bound for Lviv is pulling into the first track at Kyiv’s railway station. This is one of the most popular routes, before the war, the journey took just five hours. Although the train now takes longer, passengers will still reach their destination in another part of the country by afternoon.

A man leaves the station’s lounge area and walks toward carriage No. 8, which, according to the railway workers’ plan, stops directly in front of the door from which he exits. If you look closely, you’ll notice several soldiers subtly watching over this passenger on both sides, carefully trying not to draw attention to themselves or the man they’re guarding.

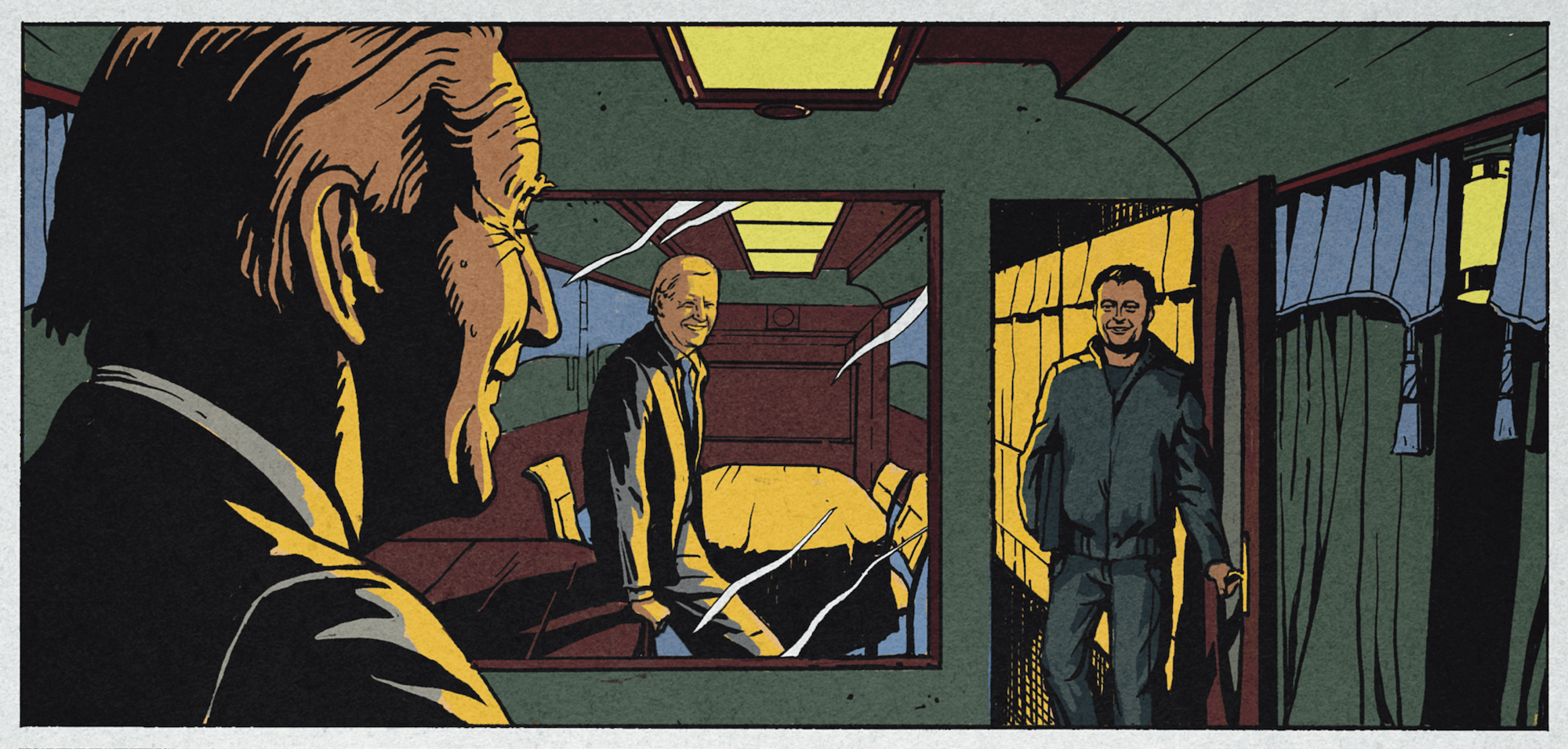

As soon as the man enters the carriage, the other passengers exchange surprised glances. He would have been impossible to miss. His tall frame, bright green tie with subtle zebra designs, and signature unruly hair immediately identify him as former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Although he had been out of office for a year, he was still the prime minister when the full-scale war began.

Johnson was the first British prime minister in history to be found guilty of breaking the law while in office. He was fined for attending a party during the COVID-19 lockdown imposed by his own government. A series of subsequent scandals and resignations eventually led to his stepping down a few months later. However, Johnson remains a steadfast ally of Ukraine. He was one of the first Western politicians to advocate arming Ukraine, and he continues to be one of the few who are not afraid to speak out boldly about Putin’s madness.

This is Johnson’s fifth visit to Ukraine since the war began. While he has previously traveled in special diplomatic cars, today he has opted for a regular train.

In the first-class carriage, Boris Johnson takes seat No. 16 by the window, facing backward. Aside from sparking an irresistible urge to snap a photo with the Western politician, his presence does not inconvenience the other passengers. Several plainclothes officers of Ukraine’s state security department, unassuming except for piercing glances, keep a watchful eye on the train’s happenings, taking strategic seats to maintain a clear view of Johnson.

Among those accompanying Johnson is a young man in a black railway uniform, a name patch on his chest reading “Shevchenko.” Baby-faced, he looks more like a teenager than the 34-year-old deputy director of the passenger company he actually is. His name is Oleksandr Shevchenko, and he’s in charge of communications and customer service. Accompanying diplomatic missions is one of the unexpected wartime duties he now handles.

***

Oleksandr is, first and foremost, a communicator. With a background in senior positions in business and banking, he joined Ukrzaliznytsia, Ukraine’s national railway company, two years before the war with the aim of transforming its communications strategy. However, he quickly realized that to turn the Ukrzaliznytsia brand into a lovemark, internal reforms needed to happen first, and only then could external promotion work through communicating them to the public. On his first day, he shared his vision on Facebook, coining the hashtag #zaliznizminy, “iron changes.” Since then, this term has come to represent the entire reform process. The focus has been on three key areas: what trains to run, where to run them, and how to run them.

Although Oleksandr spends 30–40% of his time on communications, he has many irons in the fire, participating in most of the passenger company’s projects. He is actively engaged in the modernization of railway stations and the design of railway cars, with his signature on the paperwork outlining the process of the railway’s intake of new cars. He plays a key role in planning convenient passenger routes and takes into account customer feedback, something he’s always keeping in mind. He is involved in implementing a wide range of services, including train menus, chatbots, and mobile apps. All of this can be called a new standard of service that he is passionate about.

Oleksandr’s phone never stops ringing, and he never puts it on “silent” mode, even at night, because he knows that any call could be urgent. Today, it could be about more than just communication issues; it might involve coordinating transfers, managing evacuations, assisting the wounded, or responding to station shelling, issues that require immediate attention. His workday begins at seven in the morning and often doesn’t end until after ten at night. His schedule is so packed that he can’t always add everything to his Google calendar, so he keeps many tasks in his mind. All his time is dedicated to the job, except the time he promised to his daughter. He and his wife have an agreement: on certain weekdays, he picks four-year-old Ksenia up from kindergarten and never misses her nursery school events. The birth of his daughter sparked in him a desire to do something meaningful, something she could be proud of. Transforming the railway? That’s certainly something big.

***

“Boris is, as they say, an easy-going person. He’s very easy to talk to.”

Oleksandr and I are aboard an Intercity train bound for Lviv, sharing the journey with former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Shevchenko has accompanied Johnson on most of his trips to Ukraine during the war. Although Johnson now travels almost like an ordinary passenger, without the need for an escort, Oleksandr boarded the train and arranged an interview for me on his day off. However, my interest lies less in listening to Johnson and more in observing him. Joining us is Oleksiy Pugach, Shevchenko’s colleague who manages passenger projects. He, too, has frequently accompanied foreign politicians on their visits to Ukraine.

After a brief moment, the door opens to an empty driver’s cab at the rear of the train. Johnson takes the driver’s seat and gazes out at the landscape. Through the panoramic window above the control panel, the first rays of sunlight break through the high-rise buildings, casting a golden hue over the city. Within minutes, Kyiv is left behind.

“I’m not a good artist, but I like to paint,” says Boris Johnson, reflecting on a picture he painted after his last trip to Ukraine. “These Ukrainian landscapes reminded me of a famous poem by W. H. Auden. It talks about how life continues, even when terrible things happen. It’s a beautiful poem, and it came to mind as I looked at Ukraine…”

As the train passes the Irpin bridge, it’s hard not to reflect on its significance. In the early days of the invasion, the railway managed to evacuate over 4,500 residents, mostly women and children, from the satellite town of Irpin. The tracks were later damaged by shelling, causing several empty passenger cars en route to rescue more people to derail. After the occupiers retreated, Ukrainian railway workers rebuilt the bridge in just a month, using a temporary scheme that allowed traffic to resume on one of the two tracks. In peacetime, the design and tender procedures alone would have taken at least six months.

“It’s incredible how quickly you repair things!” Johnson exclaims. During one of his previous trips to Ukraine, his train slowed down on this very stretch to carefully pass track workers finishing up the bridge. Today, we glide over it at a usual speed of 100 km/h.

“We managed to bring four million people abroad and several hundred thousand, by the way, to Britain,” Shevchenko replies in flawless English. “Now it’s important for us to bring them back. To do that, we not only need to repair what was damaged but also create new things and become better.”

“May I just say this?” Johnson smiles. “By UK standards, your trains provide excellent service! I take my hat off to you! For a country at war with Russia, you’re already doing an incredible job.”

The mention of the hat is quite fitting. During one of his visits, railway workers presented the then Prime Minister with a hat featuring the Ukrzaliznytsia logo and the inscription “Carriage numbering starts from the head of the train.” Johnson, in turn, left his own hat with the London Underground logo for the company’s museum. Later, British journalists spotted Johnson wearing the Ukrzaliznytsia hat in London, giving foreign media a chance to mention Ukraine in a positive light, not just in the context of war.

“I flew to Rzeszów in Poland,” Boris recalls his first trip, “with my guys from the SAS and SBS special forces. They took me to a place called Pudzmice,” he smiles at his struggle to pronounce the Polish city of Przemyśl. “It sounds like an antibiotic,” he adds apologetically before continuing, “Then the Ukrzaliznytsia workers took us on board. I felt like a member of the royal family, or Elvis Presley, no less. I had a bathroom, something I’d never experienced on a train before, and a lounge with luxurious sofas and a TV. And they kept bringing me food. More and more food. I could hardly move when I got off the train.”

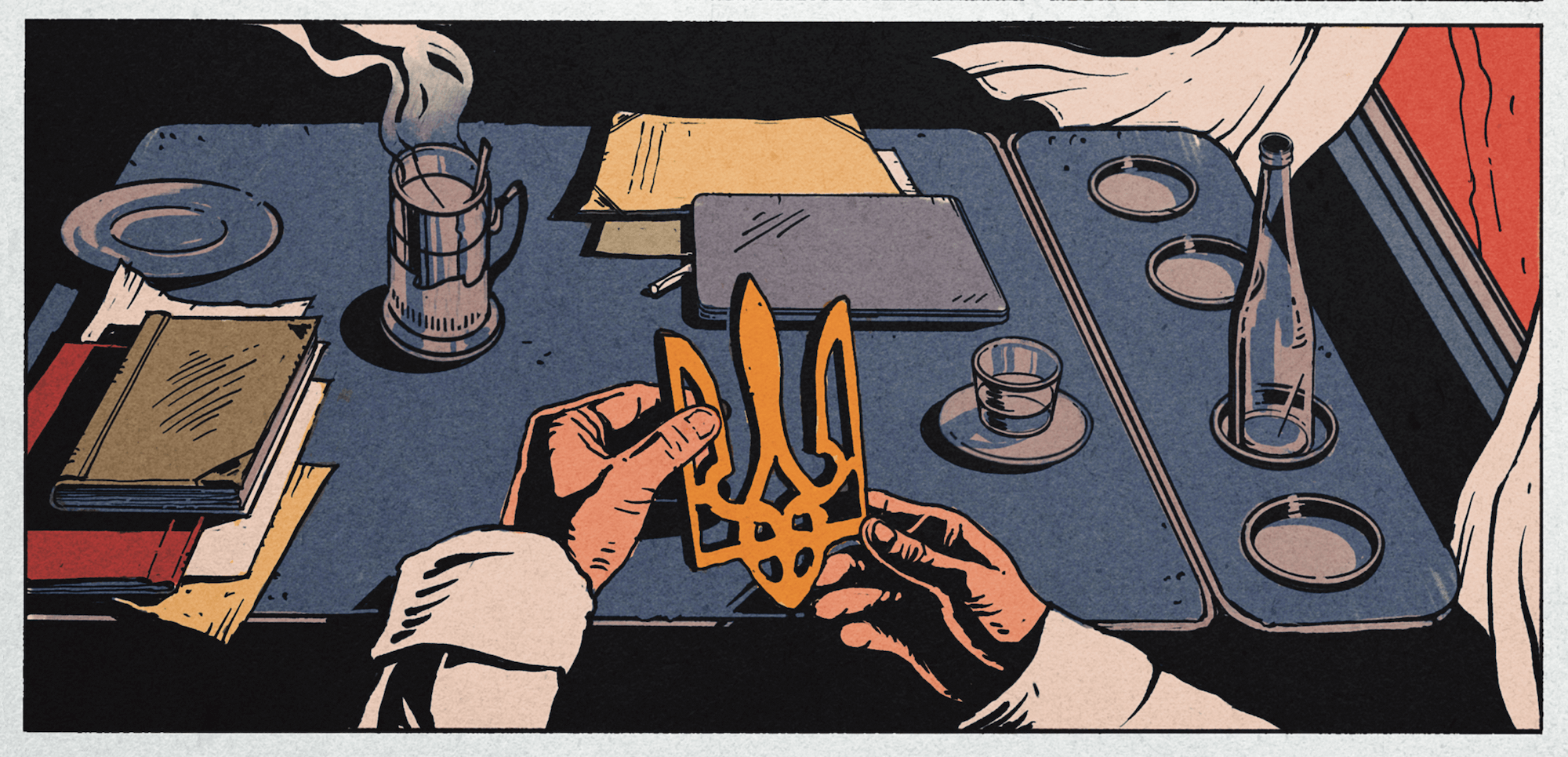

Today, Oleksandr hands Johnson a small yellow trident, roughly the size of his palm, explaining that these are given to wounded Ukrainians transported by rail for treatment as a symbol of their safety.

Johnson thanks me, and we say our goodbyes. He takes a seat by the window, opens a book, and begins reading. He often reads during his journeys, leaving notes in the margins with a pencil. Although he could use this time to work on his own book, he prefers to write by hand, which isn’t very convenient on a train. After returning to London, he’ll write a column for the conservative British magazine The Spectator, where he’ll discuss the wounded Ukrainian soldiers he met in hospitals and urge the British government and other allies not to delay in providing Ukraine with weapons.

“We feel that we influence how Western politicians talk about Ukraine,” Shevchenko tells me as we walk through the train. “They spend much more time on trains and talking to railway workers than even with the president. Official meetings last two to four hours, but they travel with us for eight to ten hours in one direction alone. So, we have a unique opportunity to make a first impression of Ukraine. As they say, you can’t make a first impression twice.”

The three of us and Oleksiy Pugach step out into the train’s vestibule. In an hour, the train will stop in Korosten, where we plan to disembark and return to Kyiv. As we wait, the guys reminisce about how railway diplomacy began.

***

In March, a few secret guests travelled to Kyiv. The Russian forces had failed to capture the capital, with the Ukrainian army holding them back in the suburbs. In response, the enemy launched rockets and artillery at the city. That day, an explosion destroyed several floors of an apartment building, killing two residents. Other missiles struck the Antonov aircraft factory and a shopping centre, scattering debris across the city and claiming another life. The once-bustling streets of Kyiv were eerily deserted as authorities imposed a 35-hour curfew, confining people to their homes or shelters unless they had special passes.

Few people knew about these guests. Around 6 p.m., Oleksandr Pertsovskyi, Director of Passenger Services at Ukrzaliznytsia, received a call from the President’s Office. The caller, Viktor Luchkovsky, a chief consultant for the Presidential Protocol Service, had an urgent request: to transport three delegations from Slovenia, Poland, and the Czech Republic to Kyiv. Even Pertsovskyi wasn’t informed who the guests were.

Politicians would always travel to Kyiv by plane, but with Ukraine’s airspace closed since the invasion, flying was too risky. Russia could easily shoot down a military plane. Traveling by car was equally perilous, with the threat of ambushes and long, unsafe routes. The only viable option was by train. Since the first day of the invasion, the railway had been coordinating with intelligence and military services, monitoring each train’s path, adjusting speeds, and preparing alternate routes in case of shelling.

The task was clear, but they had less than a day to accomplish it. Ukrzaliznytsia had never before transported diplomatic missions to a city still under attack. If Pertsovskyi felt any hesitation, it was only fleeting. For him, the formula remained the same regardless of the passenger: route, rolling stock, safety, and service.

Pertsovskyi briefed his four closest colleagues on the mission, adhering to the usual formula. He first enlisted Dmytro Bezruchko, responsible for transport planning. The train was to pick up the guests in Poland, cross the border, and deliver them to Kyiv by the next evening. The fastest route to the capital was blocked, with railway bridges destroyed and some sections under threat of shelling. A detour was planned as the main route, with several backup routes in case the Russians targeted the tracks or stations.

They needed carriages, but all available ones, including the backups, were being used for evacuations. At 1 a.m. at the Lviv station, Ihor Pleskach, one of Pertsovskyi’s deputies, found a lightly loaded train and halted it. Four luxury carriages were detached from the Kharkiv-Rakhiv train, used for evacuations.

Pertsovskyi remembered the saloon cars, relics of a bygone political era. Before the Revolution of Dignity, when Ukraine was under pro-Russian leadership, the heads of six Ukrainian railways had outfitted private cars at state expense. These cars were equipped with bedrooms, workspaces, living rooms, meeting tables, full kitchens, and separate staff compartments, a kind of presidential suite on wheels.

Each car reflected the tastes of its owner, often leaning toward socialist realist baroque with elements of a Hellenic temple. Some were modest, while others indulged in a perverse love of luxury, adorned with vintage chandeliers, antique furniture, mosaics, and gold monograms. This style, common among corrupt Ukrainian politicians of the old guard, was dubbed “Pshonka-style” after former Prosecutor General Viktor Pshonka. The most opulently decorated saloon car was simply referred to as “the golden car” by railway workers.

When the railway underwent reforms, these cars were reclaimed from the bosses and made available for public use. They were often rented by MPs, ministers, athletes, artists, and even for weddings. The “golden car” was also used for evacuations, carrying pregnant women and children. One of these cars was attached to the diplomatic train carrying the secret guests.

Conductors were needed. Since the passengers were likely foreign, English-speaking conductors were preferred. However, fluent English is outside the scope of usual responsibilities and pay grade of conductors. This challenge would be addressed later, as there was no time to spare. By 1 a.m., the four carriages and their conductors were ready at Lviv railway station.

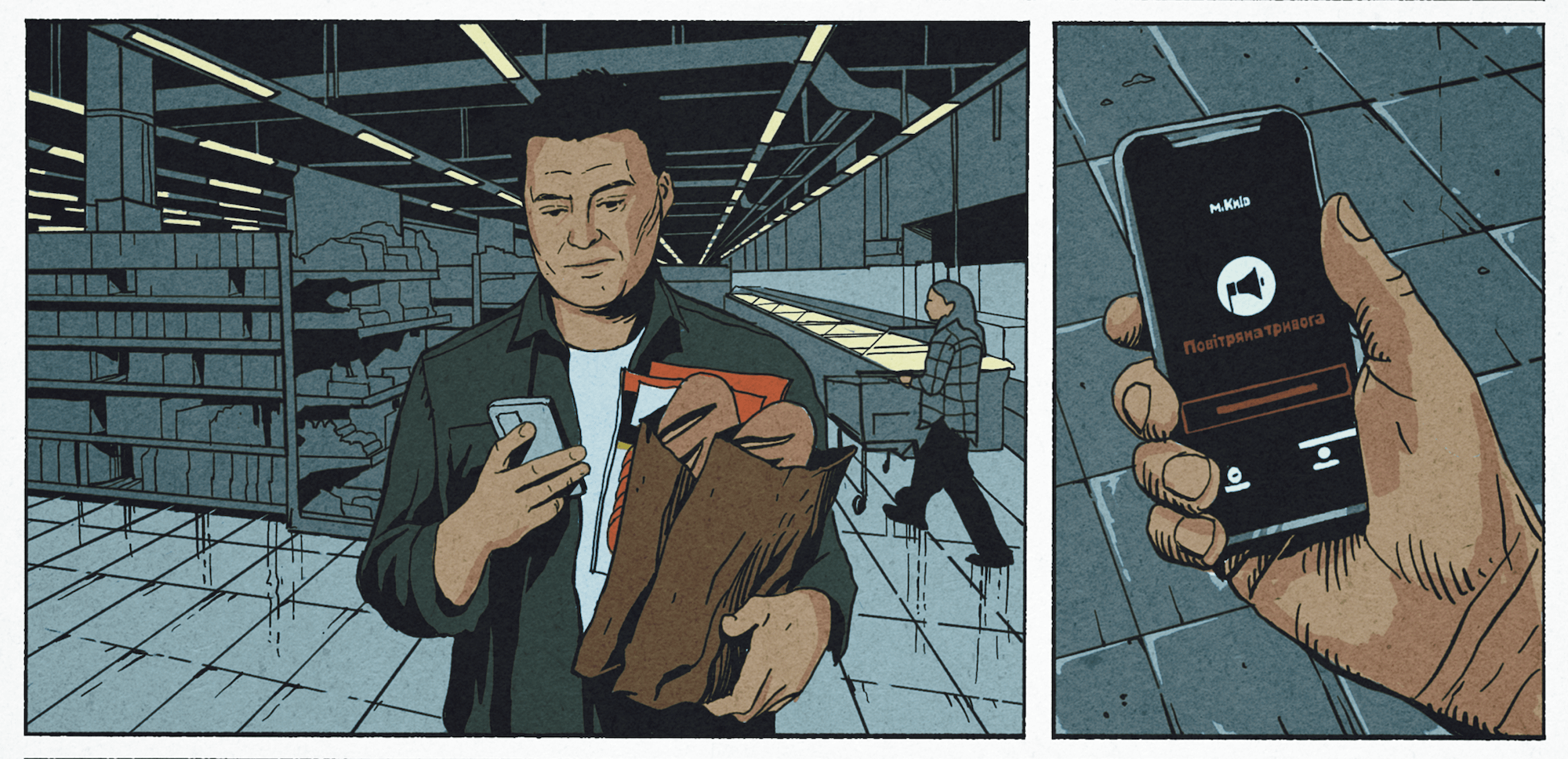

The guests must be fed. After all, they’d just get off a flight and go on for over ten hours on a train. However, dining cars had long been phased out in Ukraine, and WOG-cafe branches, which typically catered to high-speed train passengers, were not operational in the early weeks of the war. Oleksiy Pugach, the railway’s project manager, was tasked with improvising a solution.

Oleksiy was working with his colleagues at the reserve headquarters in Lviv when he received an urgent assignment. He checked his watch; there was just over an hour left before curfew. Without wasting time, Oleksiy rushed to the nearest Silpo supermarket. He grabbed some bread and sandwich slices from the shelves, but the air raid alarm sounded just as he reached the cash register. A security guard promptly moved him away from the register, apologizing as he informed Oleksiy that the store was closing. Despite his best efforts to persuade the guard, Oleksiy couldn’t reveal the truth: “Sir, a super-secret diplomatic mission is heading to Kyiv on our train, under fire, and they need something to eat.” Later, as he navigated military checkpoints during curfew, he could hardly explain why in the world he was driving around with sandwiches he had miraculously procured from a restaurant.

It wasn’t that there was nothing to feed the guests. The Lviv regional authorities provided a basic, austere set of provisions: some sausages, slices of butter, bread, and a carefully wrapped ration of two apples and one boiled egg. This might have been acceptable for railway workers, but it felt embarrassingly insufficient for diplomats.

Security was another crucial concern. The team worked closely with the state security department to establish protocols, as the logistics were complex. The mission involved meeting the guests, escorting them to the border, crossing it with them, transporting them to Kyiv, and eventually bringing them back. The state security team, which had previously organized air charters, now had to adapt to the unique demands of railway travel. They even requested additional training to familiarize themselves with the specific safety requirements for group train travel. In this way, they became somewhat integrated into the railway system. There were instances later when security services insisted on clearing stations of passengers, but the railway consistently refused, prioritizing passenger comfort as equally important.

In addition to the Ukrainian special services, each delegation brought its own security team, requiring someone to coordinate all parties involved. This was also the case during the first mission.

“Sashko, do you have your bag with you? Passport? Go back now. There’s a train at three in the morning.”

That was Pertsovskyi calling. Sashko, we know him as Oleksandr Shevchenko, had just returned home at midnight, eager to sleep, but now he had no time for rest. He didn’t know what kind of train he was boarding or where it was headed.

***

Shevchenko seemed to be a perfect fit for the job. As a deputy director, Shevchenko had the authority to make decisions on the road, understood the necessary processes, knew the right people, and was fluent in English, a skill that proved invaluable.

“Fluent” doesn’t quite capture it. As a teenager, Shevchenko fell in love with British literature and became determined to read it in the original language. His passion for literature sparked a deep interest in language. He attended a specialized school where he had the opportunity to interact with students from Australia, New Zealand, and Scotland who came to intern at the Ukrainian school in Zhytomyr. This exposure helped him get used to various English accents. He spent twelve hours a week immersed in English, studying literary English, business English, and grammar, and participating in language clubs.

In the sixth grade, his teacher recognized his dedication by giving him a collection of Thomas Malory’s Chivalric Romances. Shevchenko jokes now that only Geoffrey Chaucer is more challenging than Malory, both authors being known for their complex medieval English. But that didn’t deter the thirteen-year-old, who pored over the text with a well-worn Oxford Dictionary in hand, seeking not just translations but definitions of words. The experience deepened his connection to the language, allowing him to understand it in a more profound way. By the time he graduated, he had read a wide range of British literature, from Dickens to Thackeray.

While his family consisted of professional athletes, Shevchenko’s passion for language led him to the Faculty of Philology. He made a pact with his fellow students to speak only English with each other. He read books in their original language and sought out films without translations, which was no easy task in pre-Netflix Ukraine. He can still recite from memory the poetry of the Lake District Romantics he adored: Wordsworth, Southey, and Coleridge.

Shevchenko’s time in the United States further honed his language skills. He and his future wife spent a year working at a golf club in the Chicago suburbs through a Work & Travel program. It was during Barack Obama’s presidency, when TV host Oprah Winfrey was at the height of her popularity. Both were from Chicago, and Oleksandr unexpectedly found himself rubbing shoulders with top senators, congressmen, and businessmen who frequented the golf course.

A simple encounter during his time as a valet and waiter taught Shevchenko the intricacies of fine dining, how many utensils are needed for lobster, and the exact distance the first knife should be placed from the plate in inches. While he mused that such trivia might not be useful in his everyday life, the multicultural experience proved invaluable.

Living in the U.S. also gave him a convenient answer to the inevitable question: “Is that your voice on the Intercity train announcements? Where did you learn English?” A quick “I lived in the States” sufficed, sparing him the lengthy explanation of his deep-rooted love for English literature.

If there’s one thing Shevchenko regrets about his current lifestyle, it’s the lack of time to read. He once devoured about a hundred books a year, but since the start of the war, he hasn’t had time to finish a single one unless you count the children’s books he reads to his daughter.

Ksenia (or, as the endearing contraction goes, Ksyusha) has her father’s eyes and smile and now reads more than he does. Meanwhile, Shevchenko and his wife focus on protecting their daughter from the war. Every night, they line the bathtub with blankets as the safest spot for sleeping Ksenia should there be Russian missile or drone strikes on Kyiv. Together, they choose toys to stand guard on the windowsill, protecting her bedroom from explosions. Should it be a pink dragon tonight? Or perhaps the fairy-tale salamander?

As his daughter brushes her teeth, Shevchenko weaves bedtime stories for her. It’s a special ritual just for the two of them. “Once upon a time in a fairy forest…” he begins, sometimes improvising after long days and sleepless nights. A locomotive might unexpectedly appear amidst the dragons, princesses, and fairies, a plot twist that never surprises his daughter. She eagerly embraces these stories, occasionally contributing her own ideas. “Why don’t they get married?” she suggests when her father is at a loss for an ending.

This is the present, but in the early months of the war, Shevchenko’s wife and daughter lived in the west of the country while he prepared for his first diplomatic mission.

***

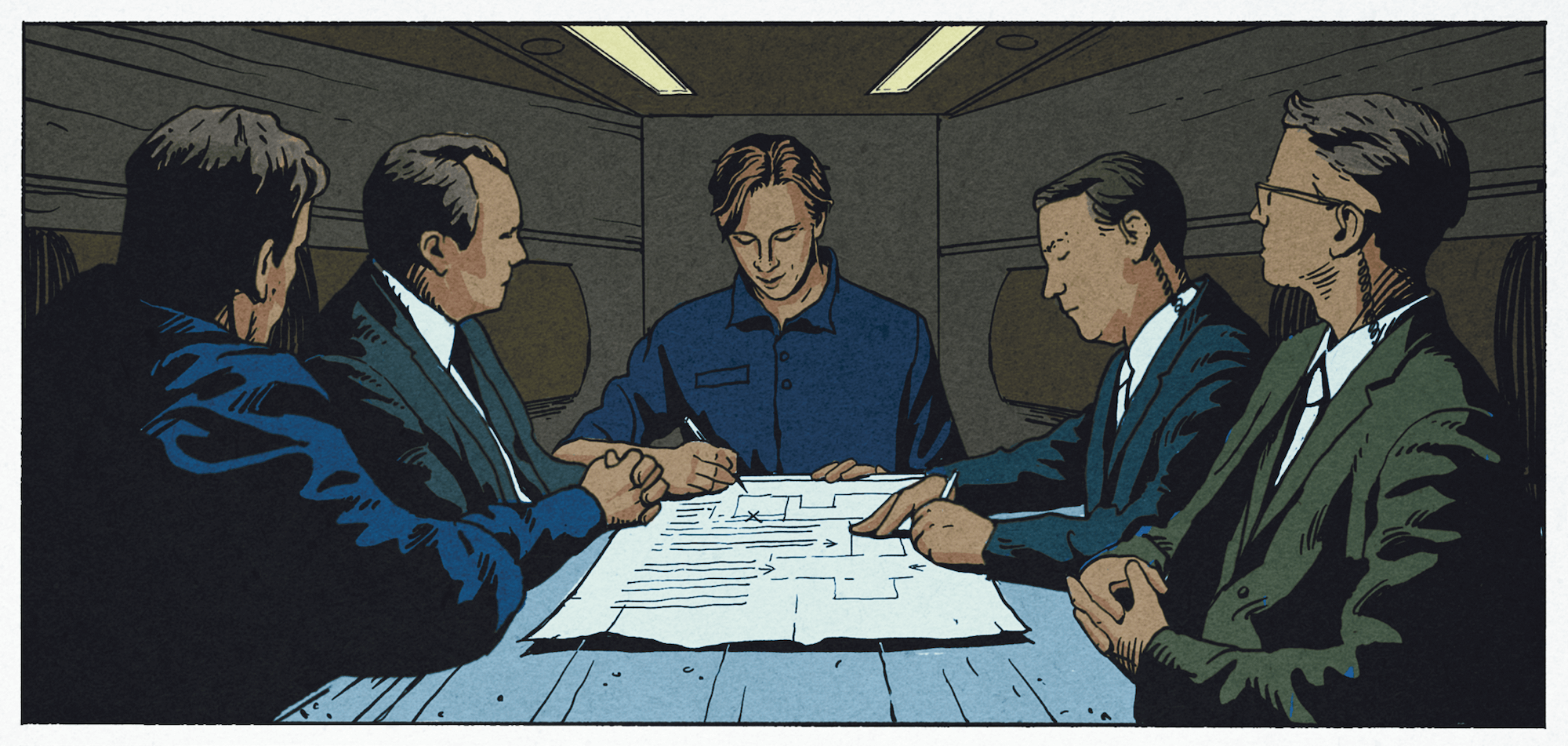

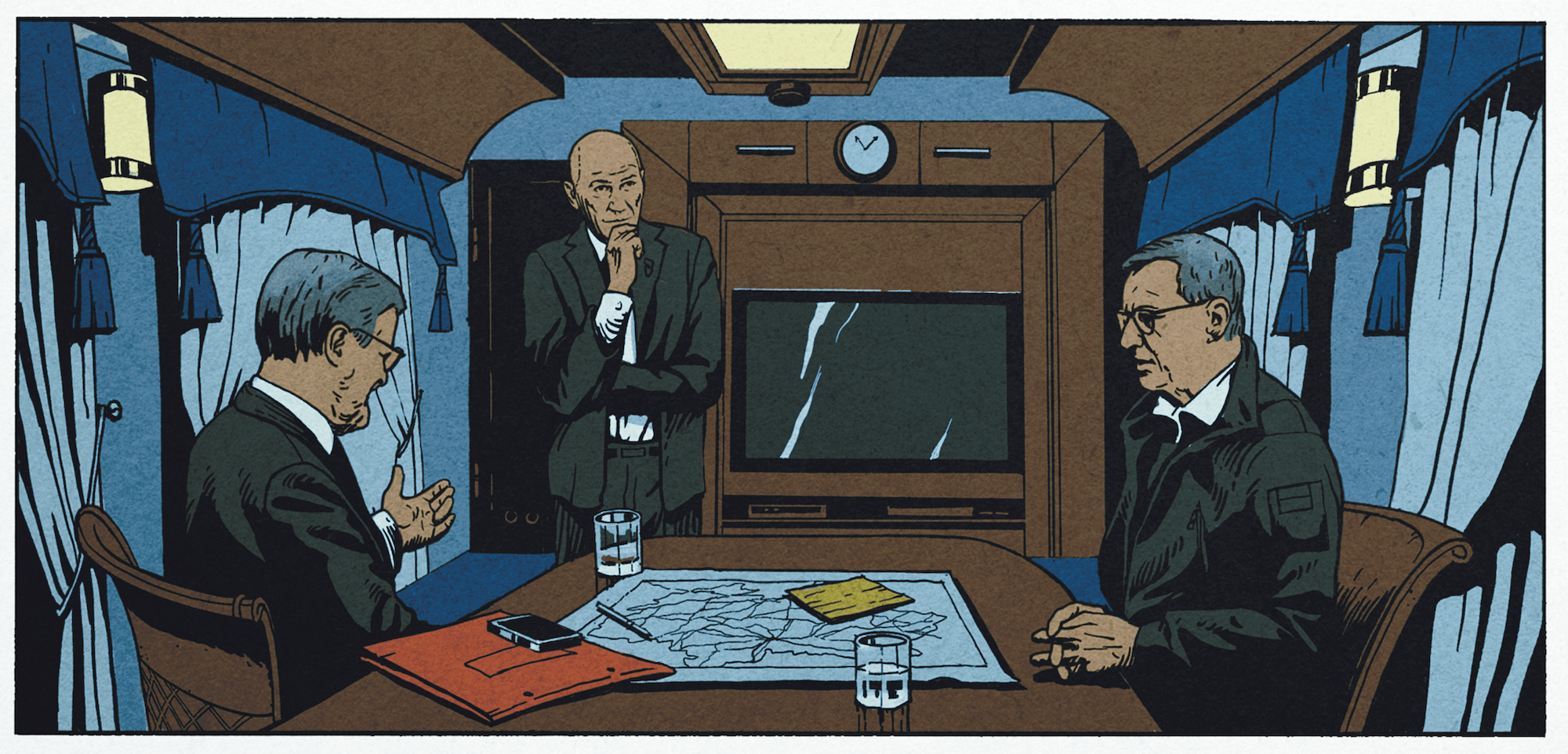

By morning, Shevchenko was already at the border with his team. The train was filled with security personnel from Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. Soon, the guests boarded, and the team’s curiosity was finally satisfied. They were hosting three prime ministers: the Czech Republic’s Petr Fiala, Slovenia’s Janez Janša, and Poland’s Mateusz Morawiecki, accompanied by his deputy, Jarosław Kaczyński, often regarded as the grey eminence in Polish politics. Each was seated in different compartments of the same carriage.

As the train crossed into Ukraine, several members of the Ukrainian security services joined them. In one compartment, the heads of all four intelligence services gathered to discuss the logistics of their arrival in Kyiv. Despite Shevchenko’s impeccable English, his linguistic skills were of little use, as none of the leaders spoke English.

“The Poles spoke Polish, the Ukrainians spoke Ukrainian, the Czechs spoke Czech, and the Slovenes spoke Slovenian,” Shevchenko recalls with a shrug. “What could I do? Someone handed me an A4 sheet and said, ‘Draw us the station.'”

So he did, sketching the station, the platform where the guests would disembark, and the exits. The guards debated in their own languages about the safest routes. Shevchenko felt more like a facilitator than an interpreter, tasked with helping everyone understand each other. During the journey, they meticulously planned every detail: where each sniper would be positioned, who would disembark first, who would block the carriage doors, who would cover the windows, and so on.

As they neared Kyiv, the prime ministers gathered in a saloon car. Shevchenko took a photograph of them leaning over a map of Ukraine’s roads. For security reasons, the delegation was to announce their visit only after they returned to the EU.

However, Mateusz Morawiecki couldn’t resist sharing the news on social media. He tweeted a photo of the leaders together, and it quickly spread worldwide. This marked the first visit by leaders of partner countries to Ukraine’s war-torn capital. As the guests, clad in bulletproof vests and helmets, stepped out of the train, the sounds of explosions from the western outskirts of Kyiv echoed in the background. “Ukraine is reminding Europe what courage is,” the Polish prime minister tweeted the following day, urging “sluggish and decadent” Europe to wake up and “break through its wall of indifference and give Ukraine hope.”

“It was a brief visit,” Shevchenko reflects, “but the atmosphere in the city and the morale boost this visit provided were unforgettable. They weren’t afraid and came to support us. It was incredible!”

This first visit paved the way for what would come to be known as “iron track diplomacy.” All subsequent operations involving the transportation of top officials, business leaders, and global celebrities to Ukraine would follow this precedent. Ukrzaliznytsia, Ukraine’s national railway, went on to transport U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, billionaire Richard Branson, actors Sean Penn and Jessica Chastain, British actor and writer Stephen Fry, TV host David Letterman, UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador Orlando Bloom, and many others. Remarkably, Ukrzaliznytsia became the only carrier in the world to host all the G7 leaders within a single year.

With each subsequent trip, the railway workers refined the logistics and protocol, ensuring both comfort and secrecy. Visits of delegates were typically announced only after they had left Ukraine, and the boarding and disembarking of high-profile guests often took place at lesser-known stations rather than central ones.

Today, as our train carries Boris Johnson to Lviv, it makes a brief stop in Korosten, a town with a thousand-year history, famous for its annual Festival of Deruny, potato pancakes, scheduled for today but cancelled due to the war. The stop is just for a minute, so the three of us jump out of the carriage and find ourselves on the platform in front of the station, a Soviet-era structure that was shelled several times by Russian forces last year.

“Let’s check the timetable to see if we can catch a train back to Kyiv,” Shevchenko suggests.

“It’s a shame this year’s Deruny Festival was cancelled because of the war,” sighs his colleague, Oleksiy Pugach, as we search for the schedule board. “I love Korosten,” he adds. “We have some amusing diplomatic stories linked to this place.”

***

Perhaps it’s no surprise that many of Ukrainian railway workers’ most stressful and often most humorous moments revolve around food, given the national trait of an unbridled desire to feed guests. One such episode occurred during Boris Johnson’s first visit to Kyiv.

This visit was more symbolic than anything else. By then, President Zelenskyy and the British Prime Minister spoke almost daily via secure phone lines. However, Johnson’s walk through the Ukrainian capital was intended to send a powerful message to Putin and solidify Britain’s reputation as a staunch military ally of Ukraine.

Just two weeks after the prime ministers of Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Poland had visited Kyiv, and a week after European Parliament President Roberta Metsola addressed her Ukrainian counterparts, followed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and EU High Representative Josep Borrell’s visit to the recently liberated Bucha, Boris Johnson arrived in Ukraine. According to The Guardian, Johnson had been debating with his security team for weeks about making the trip.

Ukrainian railway workers were determined to perfect the visit, having learned from the challenges of previous ones. They addressed even the smallest details: to eliminate the coal smell that usually permeates trains, the ventilation system was infused with “Smilyvist,” “Courage,” a fragrance specially crafted by Ukrainian perfumers.

They selected conductors with at least a basic understanding of English, outfitted them in new uniforms, planned both main and backup routes, briefed the drivers, and carefully assigned seats to the security personnel.

“We were confident we’d thought of everything,” recalls Shevchenko. “At dawn, we welcomed Johnson’s delegation. Everyone was in high spirits. Boris was delighted to be in Ukraine, greeted each of our staff members, and even mentioned how much he admired our ‘Iron People’ after reading about the railway. The atmosphere was great.”

Then Shevchenko offered Johnson a cup of tea, a time-honoured railway tradition. “Yes, please,” Boris replied, “but could I have some milk with it?” Shevchenko looked at the conductor, and the conductor looked back at Shevchenko. Silent scene.

“I have realized that we had overlooked one crucial detail: the British custom of drinking tea with milk,” Shevchenko is laughing about it now.

What followed was a covert operation, humorously dubbed “the mission to save UK-Ukraine diplomatic relations.” It was 4:30 in the morning, the train was at the border, and Shevchenko had to wake up the head of the border station to ask for milk without being able to explain why. For a moment, they even considered finding a cow ready to be milked for this critical mission, but a 24-hour gas station quickly solved the problem.

“By hook or by crook, I held the train at the station until that carton of milk arrived,” Shevchenko says with a smile. “I don’t think Boris even noticed the slight delay. It took just twenty minutes from his request until the tea was served. But we were very anxious. We wanted everything to be perfect.”

“But my favourite story is about the Korosten cheesecake,” Pugach chimes in.

Later, the railway brought in Ukrainian restaurateur and cuisine promoter Yevhen Klopotenko to design a menu of traditional Ukrainian dishes. Klopotenko also held training sessions for conductors in Kyiv and Lviv on preparing and serving these dishes, which are now featured either in his restaurant or in the Lviv station dining hall.

But in the early weeks of the war, the directive from the Office of the President or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was often simply: “A delegation is coming; make sure they’re fed.” Syrnyky, farmer’s cheese fritters, quickly became a favourite breakfast item among guests.

Almost all delegations order them for breakfast. Throughout the history of diplomatic trips, only one delegation — the Italian one — has refused syrnyky for breakfast.

“I won’t say who we were hosting,” Alexey recounts, “but here’s what happened: one of our colleagues, who tends to panic, called me at midnight in tears. I asked what was wrong, and she cried, ‘They didn’t serve syrnyky! What will the guests have for breakfast?'”

The task was clear: find syrnyky. But it was curfew—everything was closed. At 5am, as soon as the restrictions lifted, the head of Korosten station raided nearby gas stations and got every syrnyky he could find, along with some jam. Just in time, the precious cargo was delivered to the train, saving another important breakfast for Ukraine.

In addition to Klopotenko’s Ukrainian dishes, a sommelier selects special wines for each guest. For instance, during one of Boris Johnson’s subsequent visits, he was gifted wine made from grapes grown in the then-occupied Kherson Oblast. Every detail is carefully considered, with a focus on thoughtfulness and symbolism. For example, when Steinmeier, President of Germany, visited Ukraine, his car was adorned with bouquets of irises, a gesture of gratitude for Germany’s delivery of IRIS-T air defence systems. Earlier at the station, Kamyshin’s son had handed Steinmeier some toffee sweets bearing a name similar to IRIS. Waiting for him in his compartment was a thank-you card, which featured an image of one of the missile system’s batteries taking down a target. The smoke from the explosion was cleverly shaped into a heart, with the phrase “Liebe in der Luft,” Love is in the Air.

“Our work often consists of small gestures, but together they make a big impact,” says Shevchenko.

Pugach recalls another memorable story: “Remember when we added leopard print ties for the conductors?”

This was during a visit from Finnish President Sauli Niinistö, at a time when Ukraine was eagerly awaiting Finland’s decision to send three Leopard 2 tanks, along with heavy weapons and ammunition, to support the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The need for these tanks, also donated by countries like Norway, Poland, Spain, and Germany, had sparked a “leopard” flash mob on social media. Ukrainians posted photos that showed them wearing animal-print clothing, and many companies, including Ukrzaliznytsia, incorporated leopard print into their logos. The theme extended to that particular train journey, with conductors dressed in leopard print and the carriages decorated with matching textiles.

“Who comes up with all these ideas?” I ask.

“We all contribute a little,” says Shevchenko. “We have a chat group with Pertsovskyi and a few others to brainstorm ideas. I remember when a Czech delegation was visiting, we made postcards featuring their famous cartoon character, the Mole. There’s a whole series of cartoons about him and his friends. So, we created postcards titled ‘Mole Helps His Friends,’ depicting him carrying rockets. The delegation loved them and took every last one. A few months later, when the Czech Prime Minister was handing over another aid package to Ukraine, he published a photo that exactly matched the postcard—the same air defence system, the same angle, the same Ukrainian and Czech flags.”

Through these thoughtful gifts, the railway workers also aim to educate their guests about Ukraine and the war’s impact. Among the special gifts are unique bottles of wine that survived a Russian missile strike on the GoodWine warehouse in the Kyiv region. The shelling destroyed 10,000 m2 of space and over 1.5 million bottles of wine, including 15,000 vintage bottles. The few that survived bear traces of fire, serving as evidence of the attack. A QR code on the packaging directs recipients to a YouTube video, offering a 360° view of the ruined warehouse.

“When we give these bottles as gifts,” says Pugach, “we ask our guests to save the wine for the day Ukraine wins.”

Another powerful tool the railway workers use is a VR tour of cities destroyed by Russian forces, developed in collaboration with United24, a global initiative to support Ukraine. By putting on VR glasses, guests can witness firsthand the bombed-out civilian buildings, see rescuers clearing rubble, and even stand in the center of a massive crater left by an explosion.

“We see the impact of these experiences on our guests,” Shevchenko explains. He recalls an exhibition of photographs and artifacts from the first months of the war that Ukrzaliznytsia opened in 2022 at Kyiv’s railway station.

The exhibition featured not only photos from the evacuation but also items like a piece of a shot-up train, luggage shelves from Intercity trains, where, during the mass evacuation, children were placed to sleep, mattresses where mothers with children slept in the station, and baby carriages from the shelled station in Kramatorsk. Together, these elements tell a complete and moving story. Guests were often taken there before their return trip, making it the final poignant moment after their official meetings.

“I remember how Mikhal Martin, who was then the Prime Minister of Ireland, spent more than half an hour at the exhibition instead of the usual five minutes,” Shevchenko recalls. “He asked a lot of questions. He has five children himself, two of whom died at a young age, so he was probably particularly moved by what he saw. It’s important for us to convey not only the sacrifices made but also the resilience. Yes, we managed to evacuate four million Ukrainians against all odds, and we will do everything we can to bring them all back. That’s our main message: we are being shelled, but we keep moving forward.”

Our day isn’t over yet. Our return train won’t pass through Korosten until late afternoon, and the bus isn’t scheduled to leave for a few more hours. So, we decide to take a walk around the town. As we stroll, I ask the guys to share the most stressful diplomatic mission the railway has handled: the visit of U.S. President Joe Biden to Ukraine. But first, I ask Oleksandr about basketball.

***

He is 173 centimeters tall. Despite his lean build, Oleksandr doesn’t appear particularly tall, which makes it surprising to learn that he once had a stint in professional basketball.

“Everyone in my family is an athlete,” Oleksandr explains. “My parents, grandparents—three generations of sports masters. I had a choice between swimming, fencing, equestrianism, or gymnastics, but basketball became my sport. My grandfather, an Honoured Coach of Ukraine, trained women’s teams in Zhytomyr, and I trained with them.”

After school, he would head to his grandfather’s gym, where six training sessions were held daily. At first, the basketball seemed larger than him, but once he mastered it, the sport became his passion.

“When you’re good at something, you start to love it,” he reflects. “In high school, everyone was the same height, so there were no issues.”

Oleksandr was well-trained, coordinated, and fast, giving him an edge over others. He led his school team and later became the captain of his university team. When it came time to decide on a career after graduation, he followed in his grandfather’s footsteps. After studying in the U.S., he returned to Ukraine and began working as a basketball referee.

“It felt natural to me,” he says. “My grandfather coached teams and refereed games. I joined in and started refereeing, too, but I soon realized that earning forty hryvnias per game wasn’t enough to live on. Since I went to school for translation, I decided to pursue that career instead.”

However, the skills he learned on the basketball court still serve him well today.

“Basketball is a team sport, and success depends on teamwork. You’re not a lone warrior on the court. You can’t win or lose by yourself. Well, you can lose and bring everyone else down, but winning alone is nearly impossible unless you’re Michael Jordan.”

Oleksandr sees a similar dynamic at play in his work on the railway. There’s nothing you can do without a team. It’s not about individual heroes pulling off evacuations or anything else. It’s about a network working together seamlessly. If someone falters, someone else steps up. Not everyone can be fast. Not everyone can make the perfect shot from beyond the free-throw line. A good team has members with different strengths and weaknesses, and you need a solid strategy to balance time on the court, coordinate breakthroughs, and manage both offense and defence. That’s how you capitalize on everyone’s strengths and cover for their weaknesses.

“I see how the railway works. It was a revelation to me that none of the thousands of conductors who participated in evacuations and continue to work today consider themselves heroes. They say, ‘This is our job.’ The railway is a holistic organism. Yes, there are conductors, stationmasters, and trackmen, but no single person is the best at rebuilding bridges. They do it together, and no one knows their names. But their collective effort is what makes it possible. I tip my hat off to each one of them.”

It took that same level of teamwork between Ukrainian and American teams to organize the visit of the 46th President of the United States to Ukraine.

***

This story may no longer hold the suspense it once did, but back then, it was the subject of a bet between the Chairman of the Board of Ukrzaliznytsia and the director of the passenger company. Kamyshin bet a bottle of wine on President Biden’s visit, while Pertsovsky, given that Vice President Kamala Harris was already in Europe, wagered on her instead.

Pertsovsky lost; Biden did indeed visit Ukraine. On his return, he remarked that Ukrainian trains were better than Amtrak, the U.S. equivalent of Ukrzaliznytsia.

“At that time, I was traveling from Uzhhorod to Kramatorsk with our ‘Train of Unity,'” Shevchenko says. “So I wasn’t directly involved in organizing Biden’s visit. Oleksiy handled more of that, although we mainly focused on creatively planning his reception while his team managed the logistics.”

Like Oleksandr, Oleksiy has a broad range of responsibilities, including serving as the liaison between the railway and the U.S. Embassy. In February 2023, he attended a closed meeting at the embassy. While the specifics of the visitor weren’t disclosed, the level of preparation made it clear who it would be.

“Before that, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken had already visited Ukraine, so only the president could be higher,” Oleksiy recalls.

President Biden’s visit had been in the works for months, with representatives from the White House, the Pentagon, and various intelligence agencies involved in the planning. While several individuals from each institution participated, the number of people coordinating the visit eventually reached the thousands. President Biden was briefed on every detail, including the risks. And the decision on whether to come or not rested solely on him. Unlike previous presidential visits to war zones like Iraq or Afghanistan, the U.S. has no military presence or control over critical infrastructure in Ukraine, making this visit significantly more dangerous. According to U.S. media reports, both the Pentagon and the U.S. Secret Service opposed the visit, suggesting meetings near the Polish border or in Lviv instead. However, as White House Communications Director Katherine Bedingfield stated, “This was a risk that Joe Biden wanted to take.”

Ukrainian Railways had less than two weeks to prepare, and Oleksiy knows more than he could publicly share.

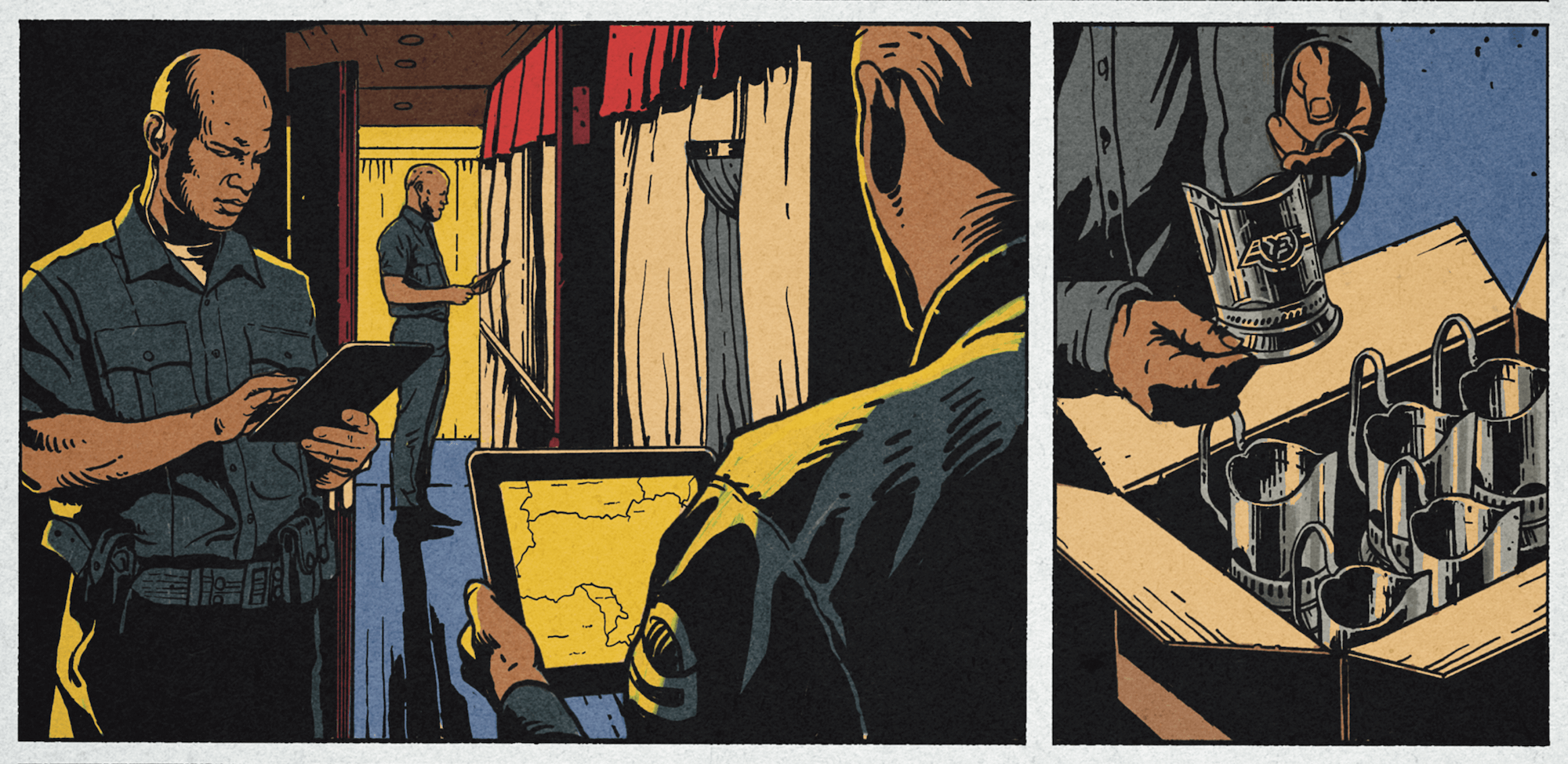

According to the plan, the railway team prepared two trains: the “Muppet” train, meant to distract attention and potentially absorb any threat, and the “Battle” train.

Before the visit, the team conducted test runs, practicing precise braking to ensure the train stopped at the exact location for disembarkation.

In Przemyśl, around 200 U.S. service members boarded the Battle train, turning it into an anthill. They worked through the night, equipping the train with a wide array of advanced technology. “You know what sets the Americans apart from others?” Pugach remarks. “They’re incredibly tech-savvy. For example, when the Poles load up, they bring trucks full of weapons, pallets of canned food, and water. But the Americans approach everything with a focus on technology.”

Special agents installed three electronic warfare stations on the train.

“Meanwhile, in our trains, only either a fridge or a microwave can be powered by the socket, but not both of them at the same time. It doesn’t work otherwise, because it’s only 3 kW,” Pugach jokes. “So, we tested the battery life and other systems. We also installed local networks and our own Starlink systems for each carriage, with backup satellite signals. It was a technological marvel.”

The next day, the technology-packed train returned to Lviv before heading back to Przemyśl to meet the guest again in the evening.

“Biden’s delegation was small: himself, two journalists, an assistant, a nutritionist, a doctor, and the rest of the staff—security personnel. Each security team member carried an earpiece and a small tablet. During those few days, we had time to become friends, so I saw that those tablets showed how and where we were moving; I could see the nearby cars and their speeds.

The map showed an overlay of air defence protection. And provided live video from two U.S. Air Force planes flying over Poland. The global system tracks every step.”

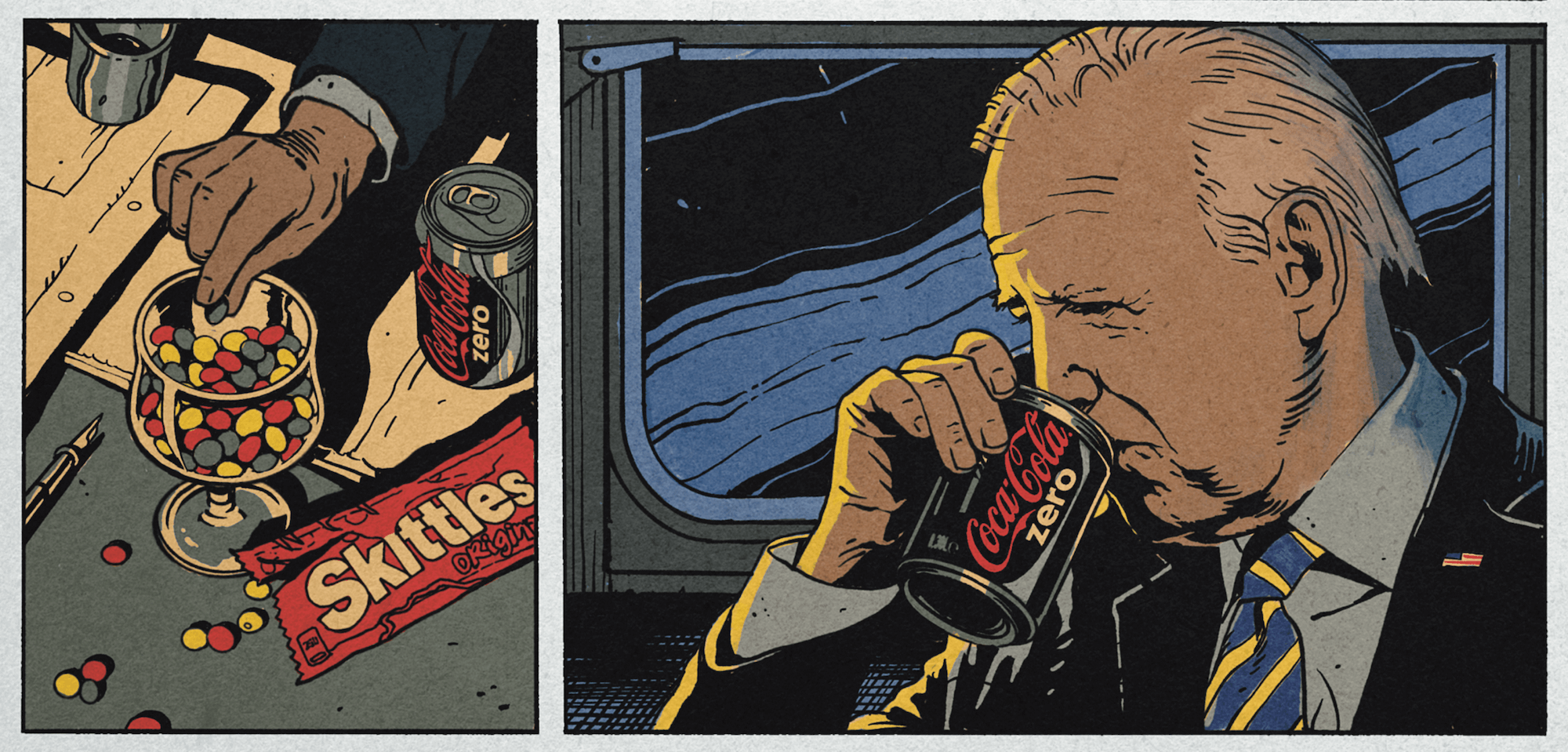

President Biden had two carriages at his disposal: one for work and one for rest. His meals were provided by his own catering service, and he drank Dr. Pepper, Coca-Cola Zero, and ate Skittles along the way.

The night before the visit, the team barely slept. A locomotive on the Warsaw–Kyiv route derailed along the Battle train’s path, and the repair crew had to clear the track as quickly as possible. As usual, the urgency couldn’t be explained—just get it done. The employees might have thought it was merely another of their bosses’ nervous demands.

Meanwhile, at the station in Poland, colleagues delayed the departure of the previous train, which could have jeopardized the entire operation. They had to convince their counterparts to hurry up without revealing the true reason, ensuring that neither the railway workers nor the passengers grew suspicious.

“We safely transported U.S. President Joseph Biden to Kyiv and back. Where Air Force One can’t fly, Ukrzaliznytsia steps in. Rail Force One is for leaders who have the courage to fight evil,” wrote Oleksandr Kamyshin, Chairman of the Board of Ukrzaliznytsia, on Telegram.

Biden’s visit to Kyiv on February 20, 2023, marked the first time since Abraham Lincoln that a sitting U.S. president visited a war zone not controlled by the U.S. military. After his meeting with Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Biden announced an additional half-billion-dollar military aid package for Ukraine, including ammunition for the U.S. HIMARS rocket artillery system.

“On the way back, near Przemyśl, we went into his carriage to greet him,” Oleksiy recalls with pride. “He was sitting at the table, happy to chat with us. He gave me a coin engraved with his signature. I’ll show it to my grandchildren!”

“Everything went smoothly,” Oleksiy continues, suddenly smiling. “What was unique, though, was that most foreigners walked around the train barefoot, in just their socks. We offered them slippers, but they refused. Biden kept his shoes on, but his entire security detail didn’t. I still can’t understand it. They don’t even take off their shoes at home, yet here they said it was so clean they felt uncomfortable wearing them.”

Just before disembarking, someone from Biden’s team mentioned they hadn’t had time to buy any Ukrainian souvenirs. The train crew responded by giving them seventy cup holders with the UZ logo, a special symbol of the Ukrainian railway.

“We gave them all the cup holders we had on the train. I estimated the cost to be about two hundred dollars and paid for it myself,” Pugach recalls. “I remember the conductors complaining that at least five cup holders went missing on every trip. Someone from a diplomatic delegation would always take one as a souvenir.”

As a keepsake of our brief time in Korosten, we took a selfie in the central square. With no luck finding potato pancakes, we headed back to the train station.

***

The only bus to Kyiv departs from a dusty station next to the market.

“When do we leave?” we ask the driver.

“At eleven,” he grumbles. “But if we load up quickly, we’ll leave earlier.”

It’s still an hour before eleven, so we can’t stray far. If the passengers board quickly, the driver won’t wait for us. We stand nearby, though it’s clear the other passengers are in no hurry to get to Kyiv.

To pass the time, the guys reminisce about an April Fools’ Day prank by their boss, Pertsovskyi. He gathered everyone involved in the first diplomatic train missions and, with a straight face, announced that Bono from U2, Hollywood star Angelina Jolie, and adult film actress Sasha Grey would be visiting. The team spent twenty minutes seriously discussing plans before Pertsovskyi finally admitted he was joking.

“The funny thing is,” says Pugach, “Bono and Jolie did eventually come to Ukraine. We’re just waiting on Grey.”

“We’ve really opened up the borders,” he continues. “If it weren’t for the railway, no one could have gotten here so quickly. Politicians, billionaires, actors, and charity representatives all use the railway because we showed them that we can guarantee safe, fast, and convenient travel. And they keep coming back because they feel safe. This has helped build a community that actively supports Ukraine.”

“Listen,” I say to the guys, “we were texting late last night while you were still working, and today, at six in the morning, we were already meeting Johnson. It’s Saturday, and you could have spent this time with your families.”

“It’s a challenge,” Oleksandr replies after a moment. “I don’t see the railway as just a job where I clock in from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. It’s a stage of life where I can make a real, tangible impact.”

“My motivation is simple. Before joining the railway, I had Ksenia, my daughter. I remember telling my wife that I wanted our daughter to grow up proud that her dad helped launch these trains. It might sound cliché, but I want to change this country for her.”

“You’ll say later, ‘Oh, those toilets with the automatic closers were installed during my tenure,'” Pugach teases.

Oleksandr laughs. “But seriously, I saw an opportunity to change something in Ukraine even before the war. That’s why I joined a state-owned company. To me, Ukrzaliznytsia, along with Oshchadbank and Ukrposhta, were these three state behemoths that couldn’t improve their services. I wanted to be part of the reforms so my daughter could be proud of me.”

He says his goal now is to create changes that will inspire people to return to Ukraine.

“A girl from Mariupol with twelve dogs, a family from Bakhmut with four kids and countless kittens that we crammed into the back of the Intercity, Nina Georgievna from Irpin in her threadbare slippers… I want to see them all on the return trip. To meet them in Kyiv near the IronLand children’s area. Our service improvements are happening alongside the evacuation of the wounded by intensive care units. That’s the price we pay and the goal we strive for. We have to bring the children back.”

One of Shevchenko’s personal dreams is to make Ukrainian Railways the most family-friendly in Europe. Among many other projects, he’s working on opening children’s areas, renovating stations to be more accessible for families, and launching family compartments.

“They’ll be ready this year. I’ll make sure of it,” he laughs.

For now, his four-year-old daughter, Ksenia, knows that her dad works “at the station.” Whenever a ring train passes by their kitchen window in Kyiv, she checks her watch and says seriously, “On schedule!” Just like her dad.

There’s still half an hour before the bus departs. Oleksiy wanders through the market and returns with plums and grapes from local grannies. To eat them right away, he pours water into a bag, pokes a small hole in the bottom, and rinses the fruit. The bus driver, unimpressed, slams the door and forces Oleksiy to buy another bag to protect the bus from drips. I can’t help but smile as one of the top managers of a massive state-owned enterprise is gently scolded by a bus station attendant.

With no benches in sight, we sit on the curb next to a garbage can, eating big, fleshy September plums.

“It’s quite a contrast,” I joke. “We were just riding in the driver’s cab with the British Prime Minister, and now we’re sitting by a garbage bin.”

“That’s the job,” the guys laugh.

Translation—Marta Gosovska

Copy editing—Marychka Androshchuk

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]