From a social perspective, an artist’s rebellion is almost always perceived as a provocation. It breaks boundaries and reveals what we often prefer not to see. This is especially striking in totalitarian societies, where the artist becomes a mirror for the repressed.

During the Stalin era, amateur photography stood no chance. Photography clubs existed only within “houses of culture” and were strictly bound by the requirements of Socialist Realism. Joseph Stalin’s death and the Khrushchev Thaw opened the door for an amateur photography movement. This was fueled by the availability of cameras — the Zorki, FED and Kyiv — and the Soviet government’s desire to find a “mass hobby” for the population. But this opened a Pandora’s box: wherever intelligent people gather without rigid control, dissenting thinkers will inevitably emerge.

Among the Kharkiv amateur photographers, some worked in factories, others in research institutes, some were film students, others still in school. Most belonged to the engineering and technical personnel, to the scientific and technical intelligentsia. They came to photo clubs to live a different life: spiritual, aesthetic and philosophical. Occasionally, they also came to be cautious dissidents.

At the same time, they were well aware that they lived in a world where everything was decided for them: the themes, the subjects, even the form of a “correct” photograph. Naturally, within the circle of Soviet amateurs, nonconformists emerged — thoughtful, stubborn individuals who could not and would not shoot, develop or print “as they should.”

Their philosophy was simple: shoot what is forbidden, do with the photograph whatever you please, speak boldly about meaning and seek new paths. This was not to convince anyone else, but to keep themselves from going mad. It was a survival strategy. That was the essence of their cynicism: they didn’t even expect the system to understand them, let alone collapse.

An artist’s rebellion does not always escalate into a revolution. More often, it is a quiet seepage of a different vision through the fingers of censorship and indifference.

The founders of the Kharkiv School of Photography (KSP) in the 1970s included Borys Mykhailov, Oleh Maliovanyi, Yurii Rupin, Evhenii Pavlov, Oleksandr Sytnychenko, Oleksandr Suprun, Hennadii Tubaliev, Anatolii Makiienko and Viktor Kochetov. In the late 1980s, new names appeared: Serhii Bratkov, Ihor Manko, Misha Pedan, Roman Piatkovka, Oleh Hrunzovskyi, Hennadii Maslov, Kostiantyn Melnyk, Hrihorii Okun, Leonid Piesin, Borys Redko, Serhii Solonskyi and Volodymyr Starko.

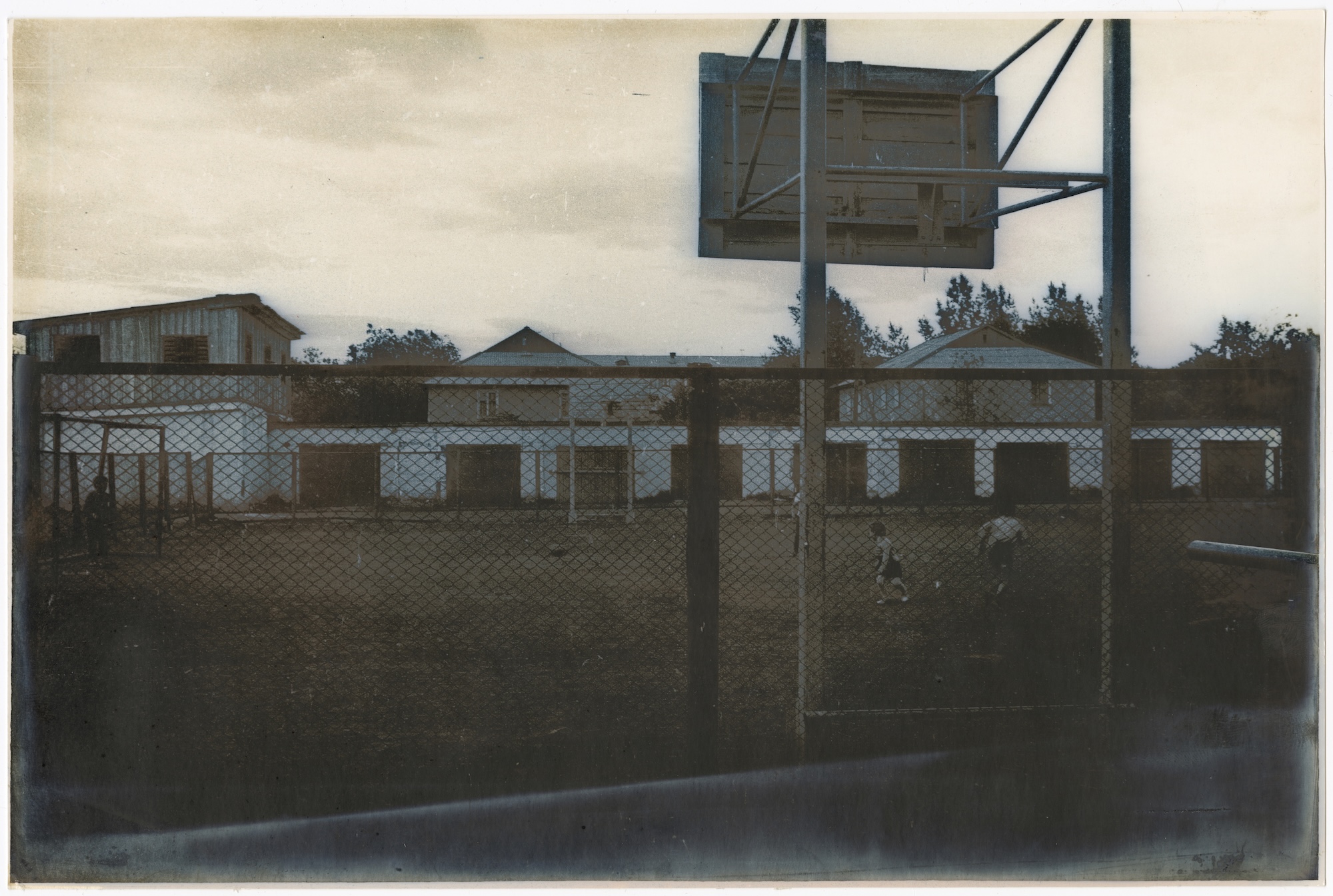

Initially, the Kharkiv photographers did not seek publicity. They gathered in kitchens and basements, exchanged albums, went on outdoor shoots and hid their images from prying eyes. They resembled an underground sect living in its own reality. Colleagues at official photo clubs found them strange, even ridiculous. But the “photo-sectarians” were fine with it: if society didn’t understand their work, it didn’t have to. Society simply wasn’t mature enough.

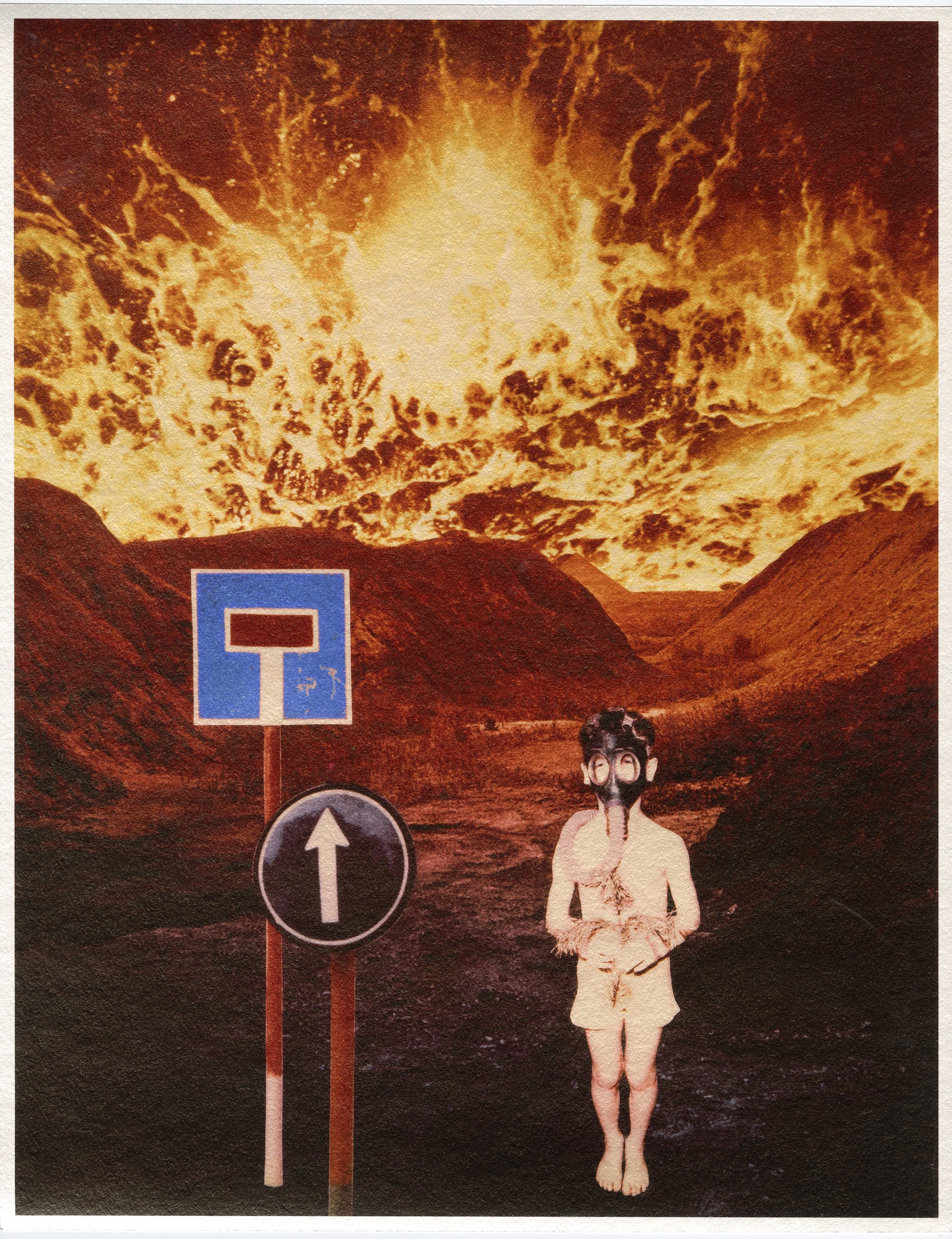

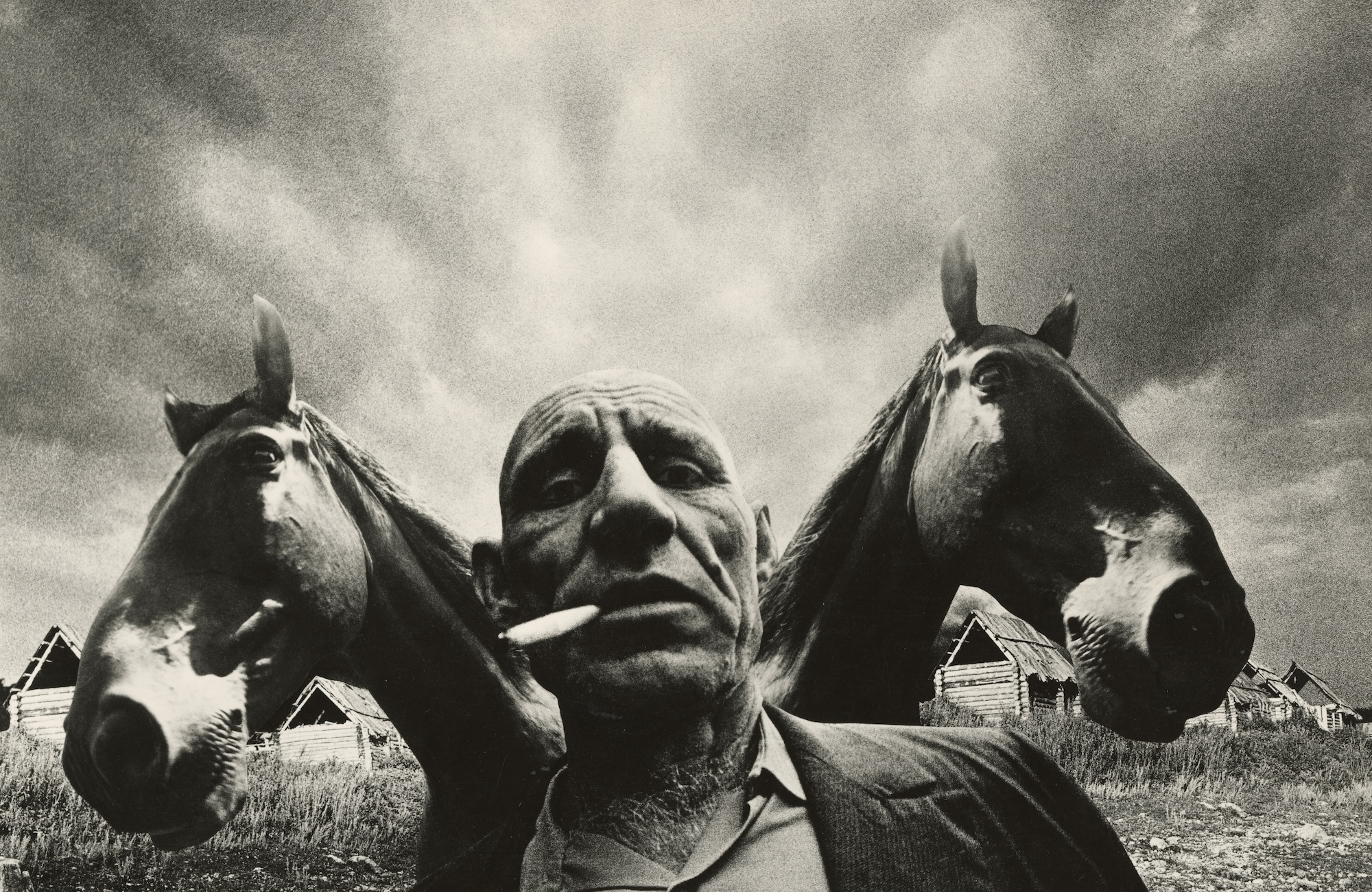

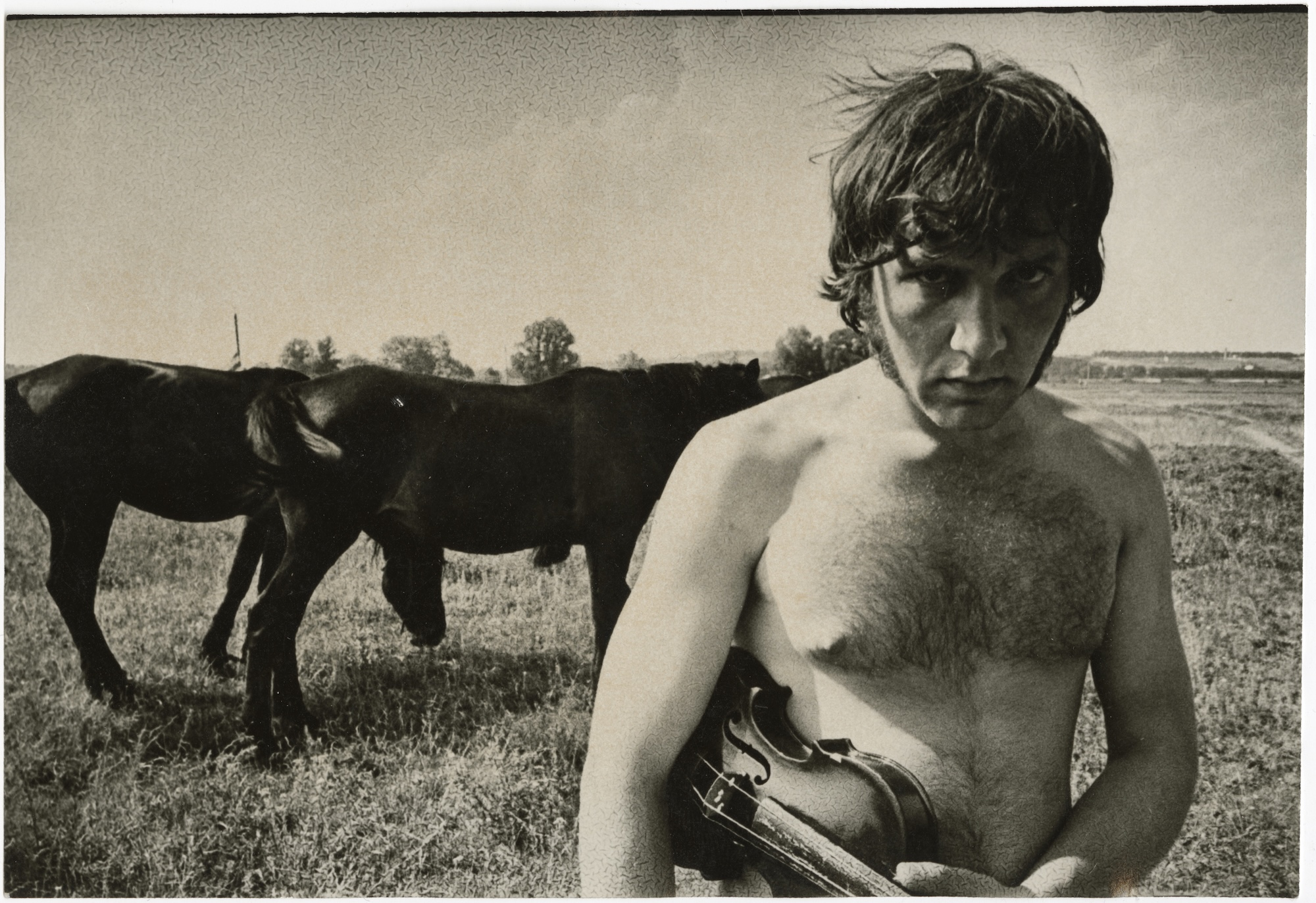

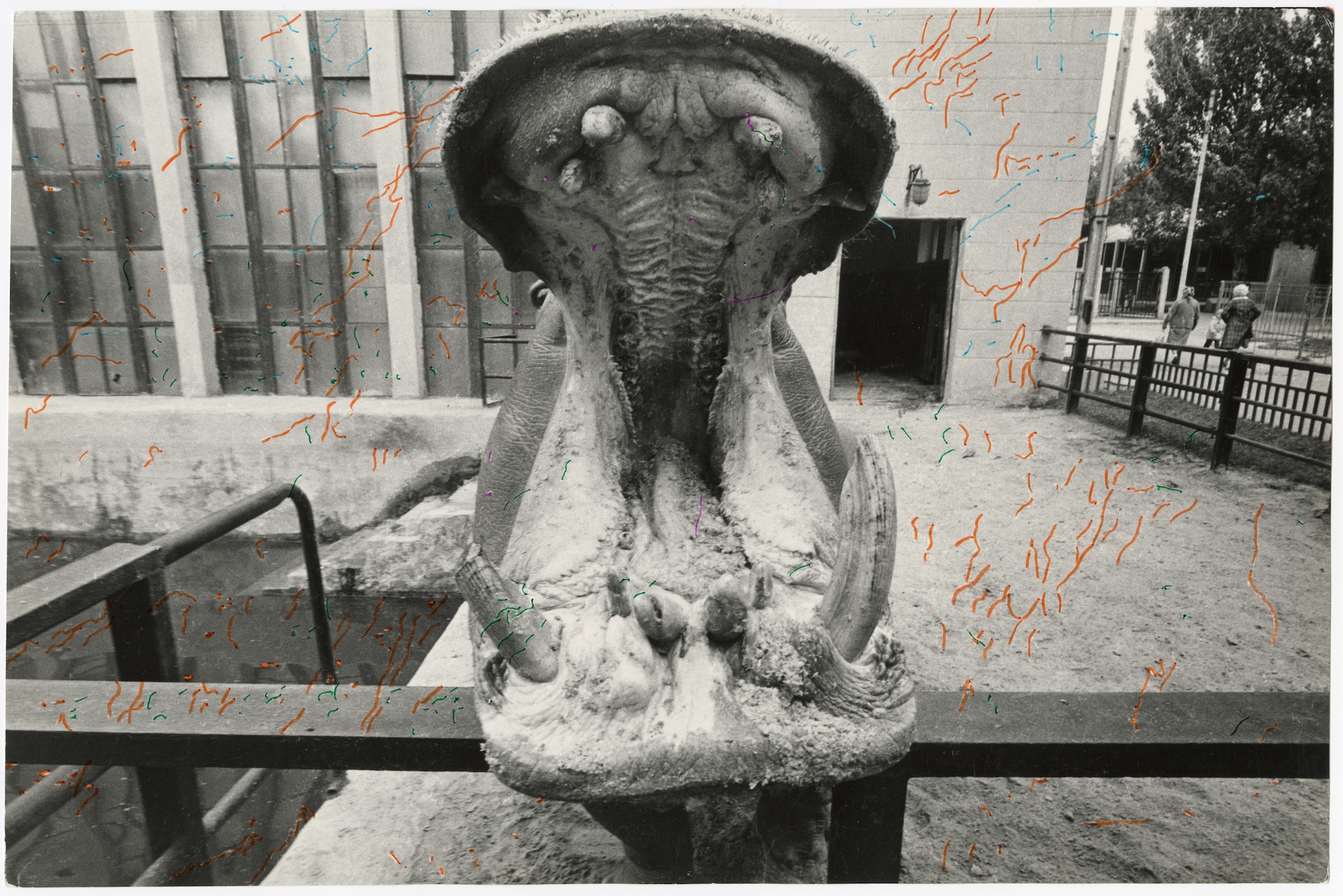

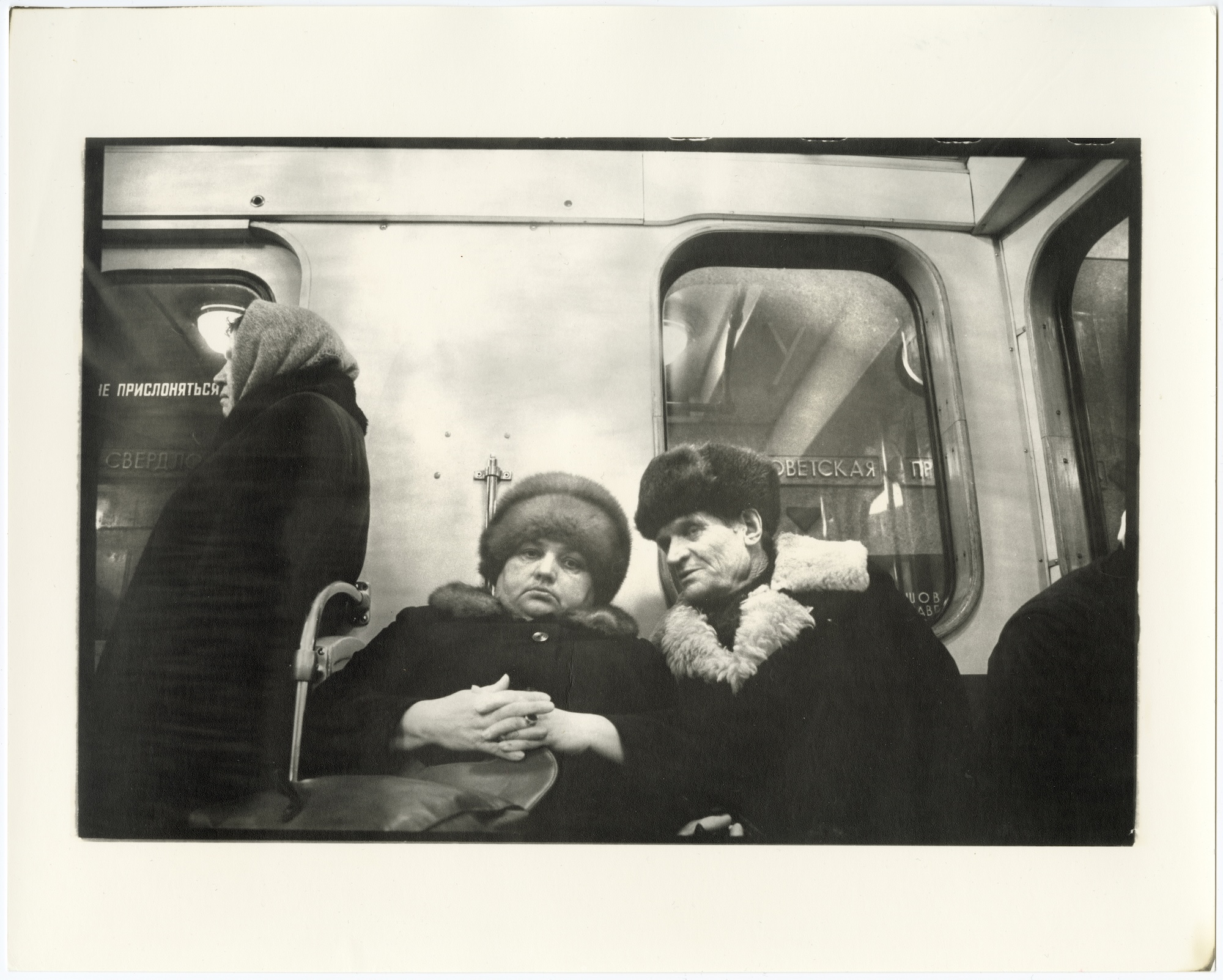

Their weapons were technical “deficiencies:” graininess, spots, crooked crops and multi-exposure overlays. They also chose “dirty” subjects: the poverty of the Soviet people, the grim streets of working-class neighborhoods, social melancholy and boredom. They intentionally rejected the standards of “correct” and “beautiful” photography. Brutality and rebellion became their new aesthetic.

They demonstratively refused to engage in dialogue because there was simply no one to debate with. In doing so, without realizing it, the founders of the Kharkiv School were clearing a path for Ukrainian photography into the world of major contemporary art.

In 1987, a group of young photographers known as the Gosprom group attempted to enter the public sphere, preparing the first major exhibition of “new photography.” Authorities reacted instantly, closing the exhibition for “immorality” and “low artistic quality.”

Another attempt followed in 1988, riding the wave of Perestroika “freedom.” Even more photographers participated, but this too was shuttered within days for “failing to meet the aesthetic norms of Soviet art.” The photographers returned to their darkrooms. Their protest seemed suppressed.

Yet, the very act of closing these exhibitions created the myth of the Kharkiv School as “forbidden” and cemented their status as underground rebels. This proved to be the best possible advertisement, better than any official catalog.

The Kharkiv School of Photography did not try to change the world. It just showed the world was rotten. These artists did not shout slogans about freedom, they knew no one was listening. They were simply free. They captured the schizophrenic Soviet reality, knowing society would dismiss their photos as bitter delusions.

When borders finally opened, the Kharkiv School achieved recognition as a contemporary art authority. One thing that was left to do was to maintain this reputation, which successive generations have done. In the 2000s, the school was renewed by a third generation: the SOSka group (Mykola Ridnyi, Hanna Kriventsova, Serhii Popov), Bella Lohachova, Taras Kaminnyi and Alina Kleitman. The following decade saw the emergence of groups like the Shilo group (Vladyslav Krasnoshchok, Serhii Lebedynskyi, Vadym Trykoz), Boba-group (Yuliia Drozdok and Vasylisa Nezabarom), Danyil Revkovskyi and Andrii Rachynskyi.

Artists do not rebel for the sake of rebellion. Their protest is a way to bring forward the time when others will finally see what they have seen all along. It is a life lived in advance, as if the apocalypse had already happened.

On April 23, 2026, the exhibition “Ukrainian Dreamers: The Kharkiv School of Photography” will open at the Radvila Palace Museum of Art of the Lithuanian National Museum of Art in Vilnius. It will be a large-scale presentation of this phenomenon of Ukrainian contemporary art in Lithuania. The exhibition is organized by the Lithuanian National Museum of Art and the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography (MOKSOP).

The opening will be accompanied by an international scholarly symposium, “‘Amateur’ Photo Clubs in the USSR and Satellite Countries (1950s–1980s)”, on April 24, 2026. The symposium will explore the photo club movement as a space for artistic exploration, nonconformity, and interaction within the official infrastructure of socialist states. The project is supported by the European Union’s House of Europe program and the Ukrainian Institute’s Visualise program.

Translation from the Ukrainian by Iryna Chalapchii