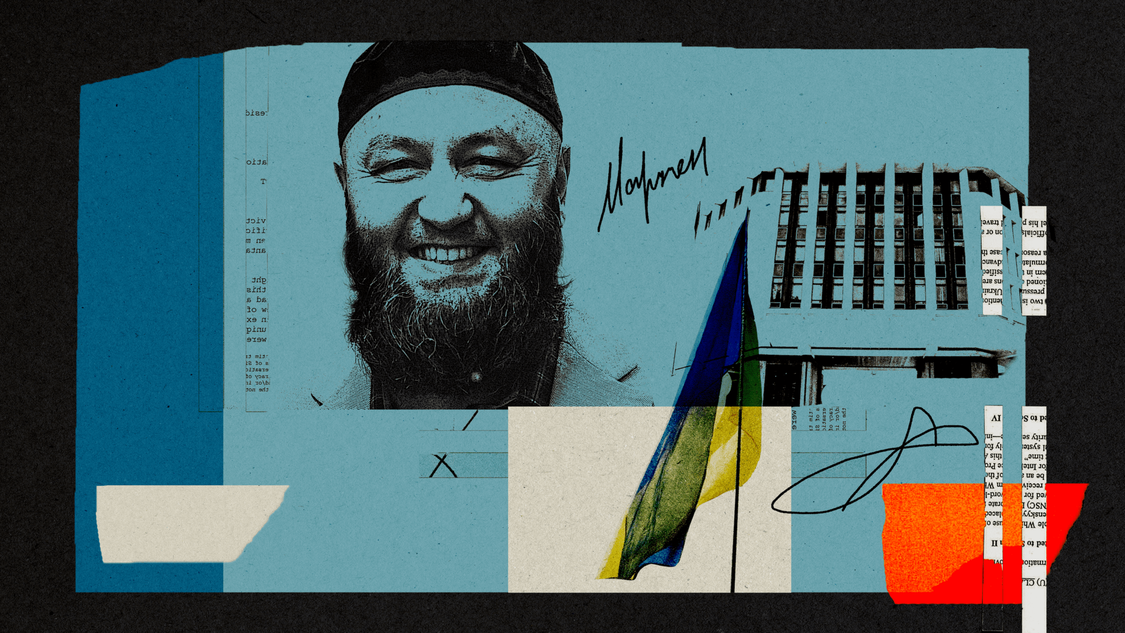

Remzi Bekirov is a citizen journalist of the Crimean Solidarity initiative and a correspondent for the Grani publication. He was born in 1985 in Bekabad, Uzbekistan, as his family, like all Crimean Tatar families, had been deported from Crimea on Stalin’s orders. Bekirov returned to the peninsula at the age of seven with his parents. He graduated from the history department of Taurida National University. While a student, he met his future wife, Khalide. They have three children.

Bekirov was detained by the FSB and later arrested in the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don as part of the largest arrest of Crimean Tatar Muslims—the so-called Second Simferopol “Hizb ut-Tahrir case.” In March 2019, over two days, Russian security forces arrested twenty-five people.

Three years later, on March 10, 2022, the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don sentenced Remzi Bekirov to nineteen years in prison, with the first five years to be served in prison and the remainder in a high-security correctional colony. The court accused the journalist of “organizing the operations of a terrorist organization” and “preparing a coup d’état.”

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

The Bekirov family has a garden where they grow fruits and vegetables. One day, a hamster started visiting their garden and the neighbors’ gardens, feasting on the harvest. Neighbors complained about the hamster to each other and vowed to catch it no matter the cost. One day, the animal came out into the garden while a neighbor of Remzi was working on the garden beds. The neighbor grabbed a shovel and chased the furry thief. Khalide Bekirova, Remzi’s wife, stepped onto the porch just as the frightened hamster ran past her, followed by the furious neighbor with a shovel and then by a worried Remzi, shouting, “Don’t touch the hamster! Don’t touch it, the poor thing!” The hamster survived. I think this is the best story to start with so readers immediately understand the kind of person Remzi Bekirov is.

Meeting at the University Dormitory

Khalide met her future husband in the university dormitory. She was studying at the Faculty of Mathematics, while he was at the Faculty of History. Her room was on the 4th floor, and his was on the 5th. At the time, Bekirov initiated and conducted tours of Crimea for university students. One of the most memorable tours for Khalide was a trip to the Chornorichensky Canyon. “He prepared us for the fact that it would be a long journey and that we would spend the night there. We brought tents and food supplies. In the end, we lost our way, stayed overnight in a place we hadn’t planned, and the backpack with food fell into the river and drifted away. We were very cold, and some people complained. But this trip is the one I remember the most. Remzi studied the history and landmarks of Crimea. He wanted to see everything up close and introduce others to Crimea. We traveled by train and bus, and someone always brought a guitar, so we sang while on public transport,” Khalide recalls.

They married in 2008, and by 2014, they had a small business: Khalide worked on designs featuring Crimean Tatar and Islamic symbols on mugs, caps, and t-shirts, while her husband handled communication with distributors and delivered orders. Khalide remembers that at the time, their products were unique in Crimea: “You could find thousands of mugs with congratulations for International Women’s Day, but not a single one with greetings for Ramadan,” she says.

Khalide also vividly remembers how, after 2014, distributors started returning their products in large numbers: “They knew perfectly well that selling such items could cause problems. There was nothing forbidden about them. But the symbolism allowed a Crimean Tatar to express their identity as a Crimean Tatar, and a Muslim to express their faith. Throughout Russia’s history of persecution and repression, everyone knew that such expressions were not welcomed there. As soon as Russia came here, we realized that our business no longer had a future,” Khalide Bekirova says.

Life on Crimea’s Freedom Street

The Bekirov family lives in the village of Strohanivka in the Simferopol district, on Azatlyk Street, which translates from Crimean Tatar as “freedom.” Since Crimea’s occupation, residents of six out of the ten houses on “Freedom” Street have been arrested by the FSB. On a neighboring street, two brothers, Teimur and Uzeir Abdulayev, Taekwondo coaches, were arrested in 2016.

Journalist and civil rights activist Lutfiye Zudiyeva believes that the arrest of Bekirov’s close neighbors and friends triggered his decision to engage in citizen journalism. Zudiyeva recalls meeting Bekirov before the creation of the Crimean Solidarity initiative. He attended political trials, live-streamed them, and wrote posts that he published on his Facebook page. Zudiyeva recounts the first meeting of the media department of Crimean Solidarity: “We had a meeting where citizen journalists who attended court hearings and homes where searches were conducted gathered. We outlined our main goals and objectives. That’s when we met many of them. Remzi was also at that meeting, and we discussed plans and ideas.”

According to Zudiyeva, Bekirov was passionate about his work, trying to attend every court hearing. He didn’t distinguish between those who were arrested based on ethnicity or religion—whether Crimean Tatars, non-Crimean Tatars, Muslims, or Christians. “If there was a report of a search or arrest, Remzi was the one who would rush to the scene,” says Zudiyeva.

Bekirov’s and Zudiyeva’s wives both recall the same story. Three weeks before Bekirov’s arrest, Archbishop Clyment (now Metropolitan) was detained in Crimea. Khalide Bekirov recounts that she and her friends, along with their children, were planning to attend an event in a neighboring village, and her husband promised to drive them there and back. Khalide laughs and says: “He fulfilled the first part of the promise, but when it was time to pick us up, he apologized and said he had an ‘urgent matter.’ We walked about two kilometers home with the kids, and I remember being a bit upset with him. Then I checked my phone and saw that Remzi was live-streaming from outside the police station where Clyment was being held.”

On November 23, 2017, Russian security forces arrested four elderly men—Kazim Ametov, Asan Chapukh, Ruslan Trubach, Bekir Degermendzhi—and eighty-two-year-old Vedzhie Kashka, a prominent veteran of the Crimean Tatar national movement, in a Simferopol café. They were accused of extorting money from Turkish citizen Yusuf Aytan, who allegedly stole money from Vedzhie Kashka’s family. During the arrest, Vedzhie Kashka fell ill and died in an ambulance. The security forces mistreated the elderly woman, handcuffing her and, according to a witness, striking her on the head with a rifle butt. When the four men were arrested in the “Vedzhie Kashka case,” Bekirov was very concerned about their health. That was when he and his colleagues first raised the issue of the detention conditions of elderly or sick people in pretrial detention centers or prisons. He continued to voice this concern after his imprisonment.

Lutfiye Zudiyeva says, “It was always surprising to see such a physically imposing and seemingly stern person on the outside—Remzi is tall and stocky—but with a very soft heart. So, when he ended up in prison, he simply couldn’t tolerate the fact that elderly people were also incarcerated. In the course of his criminal case, elderly people such as Servet Gaziyev and Djemil Gafarov were also arrested, and Remzi was very worried about their health.”

Zudiyeva recalls that during court proceedings, when communication with lawyers, relatives, and observers was more frequent, Bekirov always tried to convey brief updates on how their health was deteriorating. He urged people to speak more actively on the subject, whether with human rights defenders, politicians, or anyone involved in prisoner exchanges, advocating for the release of elderly people as soon as possible. Bekirov often said, “‘We younger people have the physical strength to resist here. But older people have minimal resources.’ He is afraid they won’t have the strength to fight until the end. This, I believe, is his main work while under arrest,” concludes Zudiyeva.

Before his arrest in 2019, Bekirov had been detained twice—both times while performing his duties as a journalist. The first was during a search in Kamianka at the house of Marlen Mustafayev in 2017. The second time he was detained later that year for a post on the social network VKontakte from eight years prior, before Russia’s occupation of Crimea. “I was worried about his safety because in recent years, activists who had been abducted were tortured with electric shocks. I was very scared to let Remzi go to the city. When he went there, I had a wild fear that he would simply disappear, and that would be the end,” Khalide confesses, adding,

Being the wife of a citizen journalist means rarely seeing your husband.

“One day he’s at a search if it’s a search day. If it’s not, he’s covering trials. As soon as he has free time, he’s off to Rostov for three days. There, Remzi, along with others, deliver parcels, attend court hearings.” This description gives a glimpse into the constant flow of politically motivated cases on the peninsula.

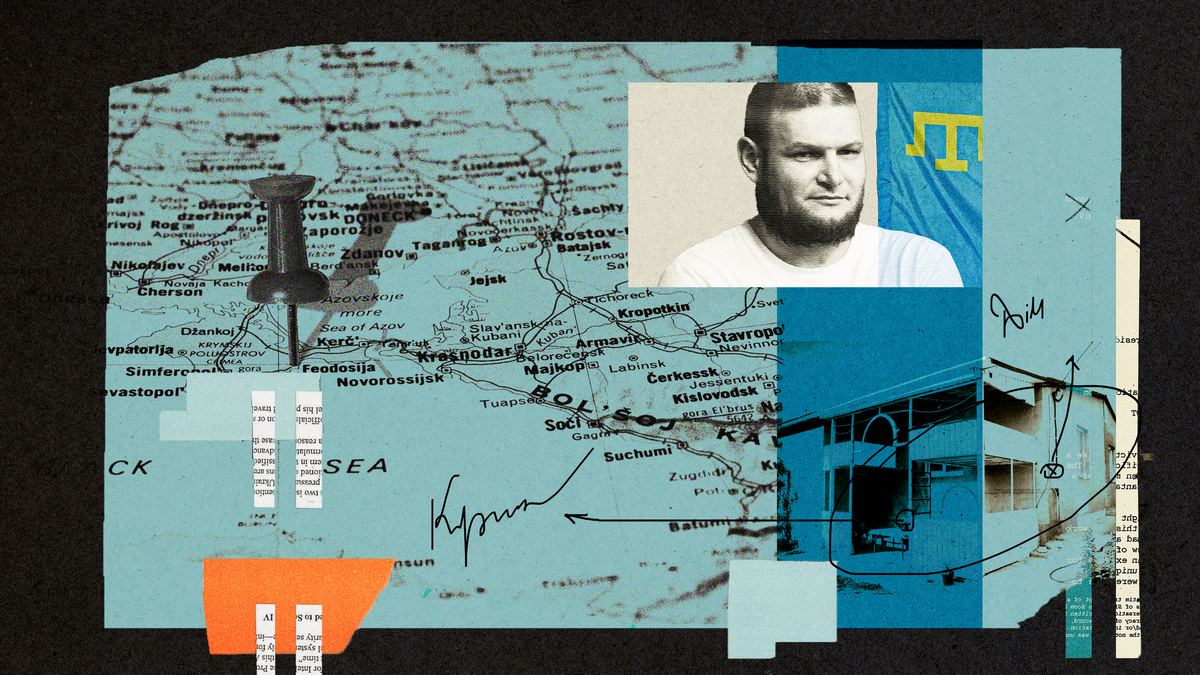

The search of the Bekirov home was conducted by FSB officers on the morning of March 27, 2019. Remzi Bekirov was not home, and Khalide recalls that the officers became visibly nervous when they realized this. He, along with Osman Arifmemetov and Vladlen Abdulkadyrov, were arrested the next day in Rostov-on-Don. The men had traveled there the day before the search to attend another court session. All twenty-five arrested would later have pretrial restriction measures imposed in Crimea. “We were tricked into not attending the court,” says Khalide. “They told us there wouldn’t be a hearing. Then, when the session began, they said it was too late to enter, even though we had been standing outside the door.” The next time Khalide saw her husband was three months later, at a court session in Rostov-on-Don.

Detention Facility on Ukrainska Street

Bekirov’s eldest son, Muhammad, then twelve years old, wanted to go to one of the court hearings in Rostov-on-Don with his mother. They arrived after traveling overnight, but the judge didn’t let him in. Muhammad could only wave at his father from the hallway during a break and spent the rest of the seven hours outside. Bekirov has been in pre-trial detention since being transferred from Crimea to Rostov-on-Don. According to his sentence, he had to spend the first year and a half in harsher conditions than in a strict-regime colony. Lawyers call such places “a prison within a prison.” Remzi has since been sent to Siberia, to a prison in the city of Yeniseisk, more than 5,000 kilometers from Crimea. Due to medical issues, Khalide is unable to visit him, as such a difficult journey could be detrimental to her health.

Khalide briefly describes the conditions in prison, as described in her husband’s letters. Prisoners are only allowed to lie in bed from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. At all other times, the beds are fastened to the wall. The only seating is a metal stool bolted to the floor. “During Ramadan, they have to eat at 4 a.m. They aren’t allowed to get out of bed at night except to go to the bathroom. They had to take food with them to bed and eat there in order to keep the fast. But there’s a TV, always showing Solovyov or Skabeyeva [Russian propagandists],” says Khalide. Bekirov constantly asks for books, but the problem is that only one parcel and one package can be sent per year. She hopes that when Bekirovis is transferred to a strict-regime colony in a year and a half, it will be closer to home.

Despite such conditions, Bekirov finds reasons for joy and gratitude. In his diary, which he has kept since the first days of his arrest, he writes: “In prison, I learned the power of unity. When you are supported by knowledgeable, sincere lawyers; when people write letters to you, people you don’t know, not just from Crimea but from all over the world; when your caring brothers send packages; when people you don’t know come to court but know you and your stance, your innocence; when your family is supported by compassionate people, and the children of political prisoners become the shared children of the entire Crimean Tatar people—isn’t that unity? Isn’t this a case of one for all and all for one? Believe me, it’s worth a lot! Many prisoners envy us, sincerely envy our unity.”

“To Dear Mother”

Bekirov’s children are waiting for their father to be transferred to a closer colony. Already, they are preparing for the future journey with their mother, especially Bekirov’s daughter Safiye, who resembles him greatly in facial features. “She gave me an ultimatum that we would go together to visit him. And sometimes she says things like, ‘How will I ever find a good husband in the future if you’ve already taken the best one, mother?’” Khalide shares their conversations.

“I miss you very much, your smile. I really miss your tenderness and care. I love you very much (heart drawing). My dear Safiye, how are you? How’s your health? Your studies? My daughter, the holy, blessed month of Ramadan is approaching for Muslims! I really hope you spend it honorably: reading the Qur’an, studying our holy book, being generous this month by giving your toys and other things to your brothers and sisters in faith; I hope you pray properly and sincerely. Maybe you’ll manage to fast. I hope you and your mom will manage to host an iftar, to feed those who are fasting,” wrote Bekirov in one of his letters to his daughter. In the corner of the letter is a drawing of a branch of black grapes, drawn with a ballpoint pen.

Khalide regularly sends her husband letters from the children. She says that their eldest son, Muhammad, usually writes briefly, reporting on family matters. Their daughter fills her letters with compliments and words of love for her father. The middle son, Salahuddin, writes about everyday life, and Khalide jokingly calls him the “household manager.” In his letters to his father, Salahuddin details what has grown in their garden and how the renovation work is going. Salahuddin and Safiye have not seen their father since he left home in March 2019.

Reviewing Bekirov’s letters, one can see many drawings: flowers, fruits, mosques. In February of this year, he sent a letter to his mother, Elvira, with photos of himself in prison robes and a drawing of a bouquet of roses. He addressed the envelope “To Dear Mother.”

From the detention center, Bekirov also sent a drawing to me.

On a piece of white sheet, he drew with a black pen the wagons in which the Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea. On each of them are written the years of deportation: 1944 and 2014.

In one of his texts written in captivity, which Bekirov called “My Deportation,” the journalist described the process of his transfer from the Simferopol detention center to the Krasnodar detention center:

“The road was long and hard. Besides feeling every bump on the wooden benches, the clanking of the iron cage door prevented sleep. But that wasn’t the worst part. Our iron cell was very cold. The heater was broken, and outside the truck, the temperature was negative twenty degrees Celsius. Moreover, there was a strong wind. Freezing, I fell into thought … When will I see my family, friends, my beautiful homeland again? When will this injustice done to me and my people end? Why are they taking me so far away from my homeland?”

This is a fragment from Bekirov’s text. Parts of his diary are published on the website “Crimea. Realities,” and the editorial board created a dedicated page for him. Most of his texts are descriptions and analyses of court sessions. Ordinary work for a Crimean citizen journalist. Only this time, it was he himself sitting on the defendant’s bench, writing about his own trial.

This text was written in April–May 2024

Translated by Yevheniia Dubrova

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано світлини авторки тексту, Олександри Єфименко, фотографії й ілюстрації із родинного архіву, а також Кримської солідарності.