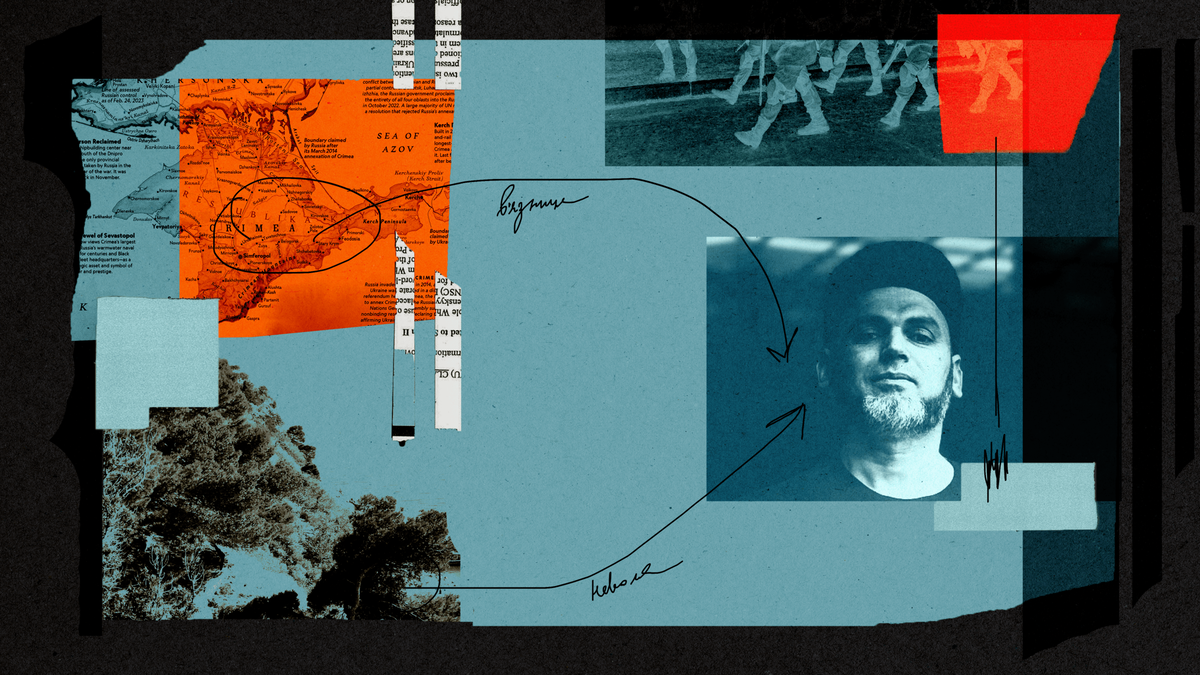

Rustem Sheikhaliev is a Crimean Tatar citizen journalist and activist with the Crimean Solidarity. He was born in 1979 in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. At the age of fourteen, he returned to his historical homeland in Crimea, where he studied at Simferopol School No. 1. He later enrolled in Vocational School No. 26 to train as a gas and electric welder, but he never ended up working in that field. For over twenty years, he was an entrepreneur, selling fruits and vegetables at a market in Simferopol.

In 2000, he married Suriya Alibayeva. They have three children.

With the onset of the Russian occupation of Crimea and the systematic repression of Crimean Tatars, Sheikhaliev became a citizen journalist. He live-streamed the unlawful persecution of Crimean Tatars and Muslims in Crimea, as well as the trials against them.

On March 27, 2019, a search was conducted at Sheikhaliev’s home, and he was arrested. He was later found guilty of “participating in the activities of a terrorist organization” (Part 2, Article 205.5 of the Russian Criminal Code) and “actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power” (Part 1, Article 30, Article 278 of the Russian Criminal Code), and was sentenced to fourteen years of imprisonment, including four years in prison and ten in a strict-regime penal colony, plus another year of travel restriction.

The entire family history of the Sheikhalievs carries the pain of deportation and persecution, much like the stories of thousands of Crimean Tatars who fought for the right to live on their own land.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

The journey home of three thousand kilometers

Rustem Sheikhaliev, who was born in exile in Uzbekistan, returned to his homeland as a teenager in 1993. His grandparents had returned to Crimea from exile not long before. Sheikhaliev traveled over three thousand kilometers from Samarkand to Simferopol to live with them. His parents were only able to return to Crimea in the 2000s.

Sheikhaliev often recalls his grandparents and their hardships, especially in his letters. His grandfather, Ismail Maksudov, voluntarily enlisted in the army during World War II, where he sustained gunshot wounds to both legs. Upon returning to Crimea after the war, he dreamed of reuniting with his family. Instead, he found his home in Simferopol empty and filled with pain: The country for which Ismail had fought against the Nazi invaders had deported his entire family to Uzbekistan and the Urals. Some relatives died along the way from cold and hunger, and they could not be buried in their native land according to Islamic customs and national traditions.

“Despite all the hardships and the oppression of our people, my grandfather stayed devoted to his faith, never parted with the Qur’an, and followed Islamic traditions. My grandmother never took off her headscarf; she usually wore two. Beneath the headscarves, she had dark, long, well-kept hair. The Qur’an was always in a prominent place in their house,” Rustem recalls in one of his letters to friends and the public.

Gulfiya, Ismail’s future wife, was taken from her native Crimea at the age of sixteen. She was placed in a cramped barrack where four deported families lived. There, Gulfiya, along with her family—including her blind mother—did not live but survived. She worked hard in a forest plantation. At the end of each workday, she was allowed to take only one wooden log to heat the barrack. Gulfiya would drag it there through the snow on cold winter evenings, navigating between the tall snowdrifts.

After returning to Crimea from exile, Ismail and Gulfiya began building a house because strangers occupied the homes where they had been born and from which they were expelled in 1944. Their grandson, Rustem, studied to become a welder during the day and worked manual labor in the evenings to save money for the construction. As a young man helping his family establish a home, he dreamed of building a house where the laughter of children and grandchildren would be heard. They would fill it with love and the joy of living freely on their land.

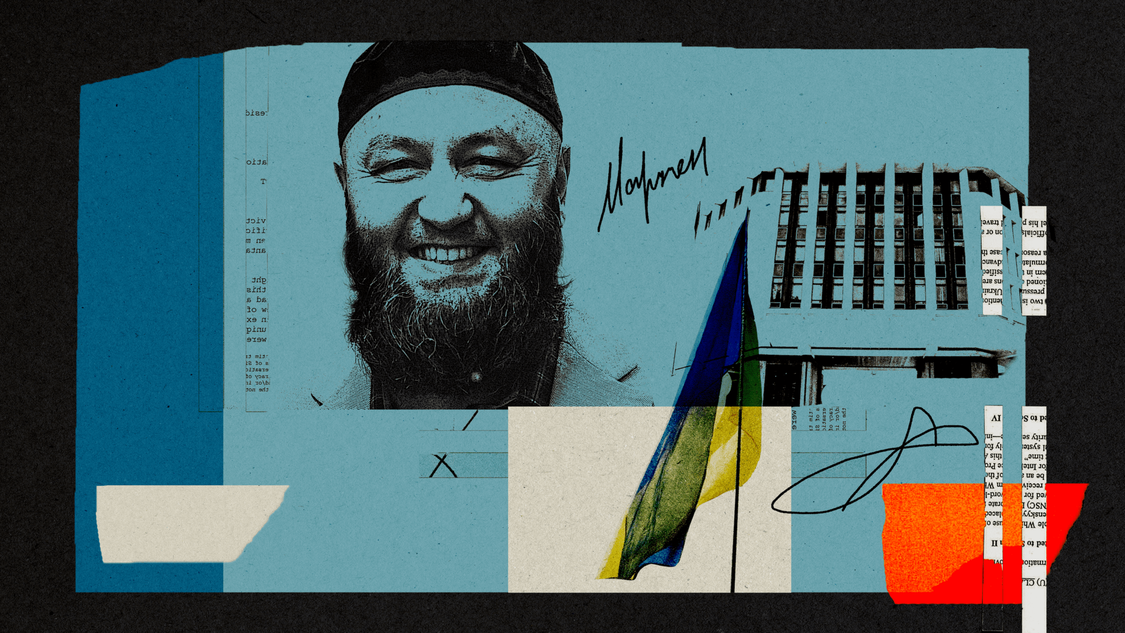

As an adult, Sheikhaliev worked at Bazar meydanı, a market square—one of the historical sites in Simferopol. For centuries, this market was a place where watermelons, melons, nuts, peppers, and sweets were sold. Sheikhaliev sold fruits and vegetables, and local housewives came to him like family—he was loved for his simplicity, honesty, and openness.

It was at that time that Sheikhaliev met the woman with whom he wanted to build a home for himself, their children, and grandchildren.

Suriya, his future wife, was also born in Uzbekistan, in the same city of Samarkand, in the same maternity hospital. She returned to Crimea in 1992 and lived in Simferopol.

Wake up, bandits have come

When the Russian occupation of Crimea began in 2014, and mass searches and arrests of Crimean Tatars commenced, Sheikhaliev decided he had to tell the world the truth about the repression of Muslims. He was especially worried about his friends, who were being systematically arrested by the FSB following the annexation, violating all possible human rights. Sheikhaliev took his phone and tripod, and began filming the unlawful arrests.

In 2016, Sheikhaliev covered the case of his friend Rustem Ismailov, whose house was searched and who was accused of “participating in the activities of a terrorist organization.” He was tortured in the FSB building in Simferopol and, in February of the following year, sent to a psychiatric hospital for a forced psychiatric examination. Sheikhaliev recorded everything he could on camera, posting the videos online to try to raise awareness of the case.

In 2019, he traveled to Rostov-on-Don, where he live-streamed from the North Caucasus District Military Court. That day, five Crimean Tatars received lengthy prison sentences for alleged “participation in the activities of a terrorist organization” (the same Article 205.5, Part 2 of the Russian Criminal Code, that was applied to most Crimean political prisoners): Teymur Abdullayev was sentenced to seventeen years in prison, his brother Uzeir to thirteen years, Rustem Ismailov to fourteen years, and Emil Dzhemadenov and Aider Saledinov to twelve years each.

Sheikhaliev also helped the families of political prisoners, organized celebrations for their children, and delivered food and essentials to unlawfully arrested journalists, activists, and human rights defenders. He wrote extensively on social media about the abuses perpetrated by the Russian authorities in Crimea.

“He understood that they would come for him sooner or later, but he couldn’t act any other way,” says Suriya.

“If I don’t go, and somebody else decides not to go, then who will help?” Sheikhaliev often repeated.

Suriya always supported her husband. However, each time she heard about another arrest of a Crimean Tatar activist, she felt a deep unease. She understood that sorrow could come to the Sheikhalievs as well.

On March 27, 2019, at 5 a.m., Rustem and Suriya were awakened by their eldest son, Renat: “Wake up, bandits have come!” The Sheikhaliev family was preparing for their morning prayer. Before breaking into their home, Russian security forces shone flashlights into the dark windows of the room where the children were sleeping.

They could hear shouting by the front door. In an instant, armed, masked men in camouflage burst into the house. “Hands up! Hands against the wall! Face down on the floor!” they ordered. Sheikhaliev calmly replied, “Make up your mind. Which one of these should I do?”

Sheikhaliev was given five minutes to get ready. He was handcuffed while Suriya and their three children—Dzhelyal, Renat, and Zulfiye—were ordered to silently wait in the kitchen.

“When Rustem’s grandmother spoke about the deportation she endured, I couldn’t feel her pain. It was only that morning, when they took Rustem away, that I understood the full tragedy. My husband relived her fate,” Suriya says.

“I keep going back to that morning in my mind. Strangers were walking through my house, stomping around, turning everything upside down, taking charge,” Sheikhaliev later wrote from captivity. “They put handcuffs on me and, under strict watch, allowed me to take a single step forward to say goodbye to my family. To my parents. That day, I didn’t know it would be the last time I’d see my father. That I wouldn’t be able to attend his funeral.”

During the search of the Sheikhaliev home, Russian security forces planted a banned book about Islam and confiscated religious publications that were not prohibited. Then, the investigator told Suriya to quickly gather her husband’s belongings.

“And I told them, ‘I won’t be gathering anything. He will return.’”

Suriya had no idea that the very next day, she wouldn’t even know where her husband was. Nor did she know that in those same days when Sheikhaliev was arrested, twenty-four other Crimean Tatars were also detained. All of them were later accused of involvement with Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Captivity

Two days later, at the end of March 2019, twenty-five Crimean Tatar prisoners of the Kremlin were already in a pre-trial detention center outside Crimea, in Rostov-on-Don. Suriya learned from a lawyer that her husband was among them. He remained in this detention center until September 2019. During this time, Suriya received almost no news from him, as his emails somehow never reached her. Eventually, Suriya found out that Rustem’s health had deteriorated: He was suffering from high blood pressure and nosebleeds that could not be stopped for a long time.

Five months later, the prisoners of the so-called “Second Simferopol group” of the Hizb ut-Tahrir case were sent back to Simferopol, where the investigation began. Then Suriya was able to communicate with her husband for the first time, but the visitation allowed by law was strictly prohibited.

Six months later, the detained Crimean Tatars were taken back to Rostov-on-Don for the trial.

Suriya, along with their eldest son Renat, traveled to the trial in Russia to be present when Sheikhaliev’s verdict was announced. All those arrested on March 27, 2019, were sentenced on the same fabricated charges of “participation in the activities of a terrorist organization” and actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power.” Sheikhaliev was sentenced to fourteen years in prison.

Not long after, Suriya received a message from her husband that he was already in another Russian colony—in Yeniseysk, in the Krasnoyarsk Krai. Sheikhaliev is still there today.

Sheikhaliev’s wife and children manage to communicate with him once a week via email. Phone calls are prohibited. The Qur’an helps Sheikhaliev a lot in the inhumane conditions of the totalitarian system.

“People receive unheard-of sentences just for being Muslim,” Sheikhaliev wrote in one of his letters.

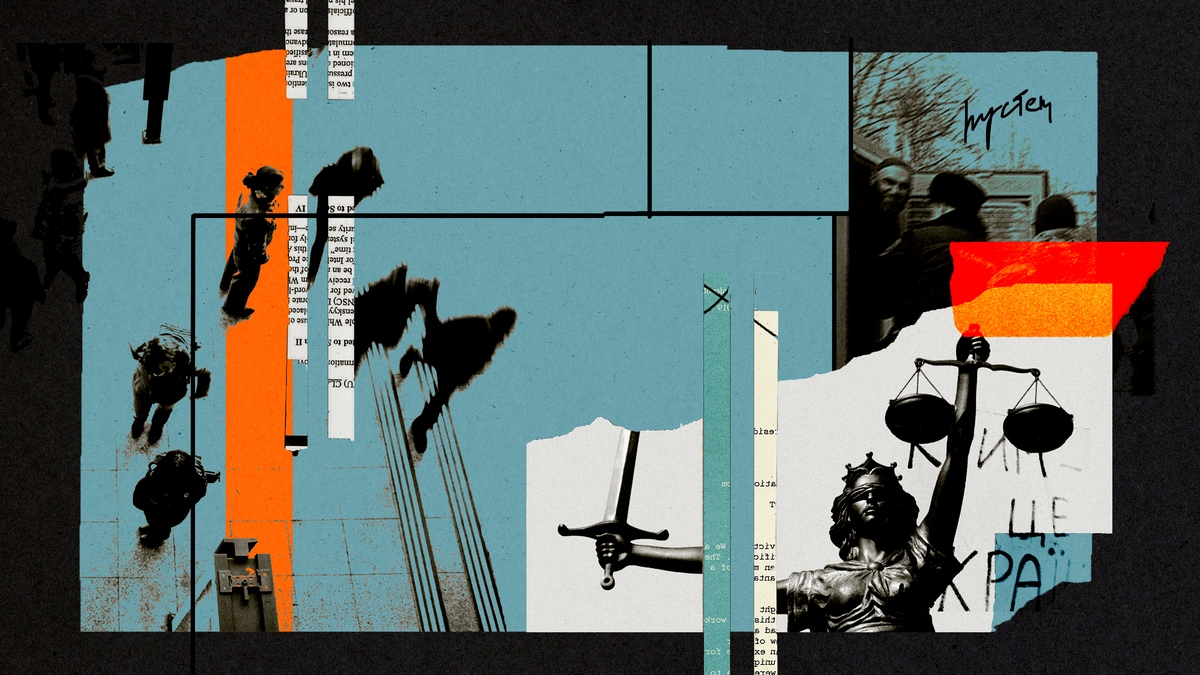

Olha Kuryshko, deputy representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, explains: “Religious affiliation serves merely as a pretext for arrest. In general, Russian legislation contains various grounds for bringing individuals to criminal responsibility and uses them to eliminate specific individuals or groups. In Crimea, to which the Russian Federation extended its legal framework after 2014, the occupying administration applies persecution and unlawful detentions against those perceived as a potential threat to its own existence.”

The persecution of Crimean Tatars by the occupying authorities in Crimea is a systemic practice and an established policy, says Kuryshko, referring to a document that confirms this: the decision of the European Court of Human Rights of June 25, 2024, in the case of Ukraine against Russia (regarding Crimea). “In particular, the Court noted that the persecution by the occupying administrations was not random and was directed against Ukrainian activists and journalists, as well as Crimean Tatars who were considered supporters of Ukraine. The Court concluded that the persecution and sentencing of ‘Ukrainian political prisoners’ were a striking example of repressive persecution, abuse of criminal legislation, and general suppression of political opposition to Russian policy in Crimea. The Court also noted that Crimean Tatars are a particular target for the occupying authorities, with documented instances of intimidation, pressure, physical attacks, warnings, and persecution through judicial measures, including bans, home searches, detentions, and sanctions,” Kuryshko summarizes the content of the document.

In July 2019, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling on Russia to release all Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar political prisoners, including Sheikhaliev. In December of the same year, the international NGO Committee to Protect Journalists included four Crimean Tatar citizen journalists in its special report about those who uncovered the truth and were deprived of their freedom for doing their job. Among them was also Sheikhaliev. The Russian human rights center Memorial also recognized the Crimean Tatar human rights defender and citizen journalist as a political prisoner.

“Prison has not changed him.”

During this year’s Kurban-Bayram, Suriya posted a short video from her husband on her Facebook page, in which Sheikhaliev congratulated all Muslims of Crimea on the great holiday of sacrifice. Under the video, Suriya wrote: “He has lost a lot of weight.”

About his time in captivity, Sheikhaliev wrote: “The radiator doesn’t work; dampness and mold crawl into every corner of the cell like some beasts. They have already reached the ceiling and turned into fungus, which significantly affects my health. My cough worsens, turning into a suffocating (allergic) wheeze, so I have to keep the window open, which further lowers the temperature in the cell, and my feet freeze. Sometimes, it’s impossible to warm up, and I catch colds. As for the food, it’s best not to mention it at all—after eating, I get stomach pains, sharp discomfort, and heartburn. Whether it’s from the half-baked bread or the mysterious margarine, which leaves the dishes impossible to clean, I can’t say . . .”

Soon, Sheikhaliev would face serious health problems: hypertension, gastrointestinal, and kidney issues, as well as reoccurring dental problems. The administration of the Russian colony would not respond to dozens of requests made by Sheikhaliev, asking for a medical examination and medications. They would not even allow a heater to be sent to the prison cell, which Sheikhaliev’s relatives wanted to purchase at their own expense to help him.

But despite the terrible conditions, Suriya notes: “The prison has not changed him. Justice and honesty still matter the most to him.”

In his letters, Sheikhaliev often reflects on what happened. But he never regrets his choice to speak the truth. He is the voice of those who are not heard.

“We will never bow our heads,” Sheikhaliev writes, “because we have nothing to be ashamed of. Many are surprised by the support our people show each other.”

But it’s always been like this: Take one of us—ten will come, take ten—a hundred will come, and if you take a hundred, a thousand will come. That’s our people, like a single organism.

In captivity, Sheikhaliev still manages to support his family. He gives advice on household matters. He asks about life in Crimea, inquires about the Crimean Tatar activist movement on the peninsula, and repeatedly emphasizes that the just struggle must continue. He believes that, despite everything, he and his wife will be together sooner or later.

(Un)fulfilled dream

Sheikhaliev’s dream from when he was a young man came true: He did build a big house for his family. He began working on it twelve years before his imprisonment and built everything himself. He finished the roof and several rooms. He planned to plant a garden where he would grow fruit. The construction lasted for years, and Sheikhaliev invested his soul and heart into it.

Suriya and the children only managed to settle in the new house in 2015. Sheikhaliev never got to enjoy it with his family. To live in his own house. To hear the laughter of his grandson, who will soon turn one in October 2024.

At the local market, people still ask about Sheikhaliev. They often send him sweet dates and notes of support.

This text was written in May–July 2024

Translated by Yevheniia Dubrova

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано світлини із родинного архіву, а також Кримської солідарності і Кримської платформи.