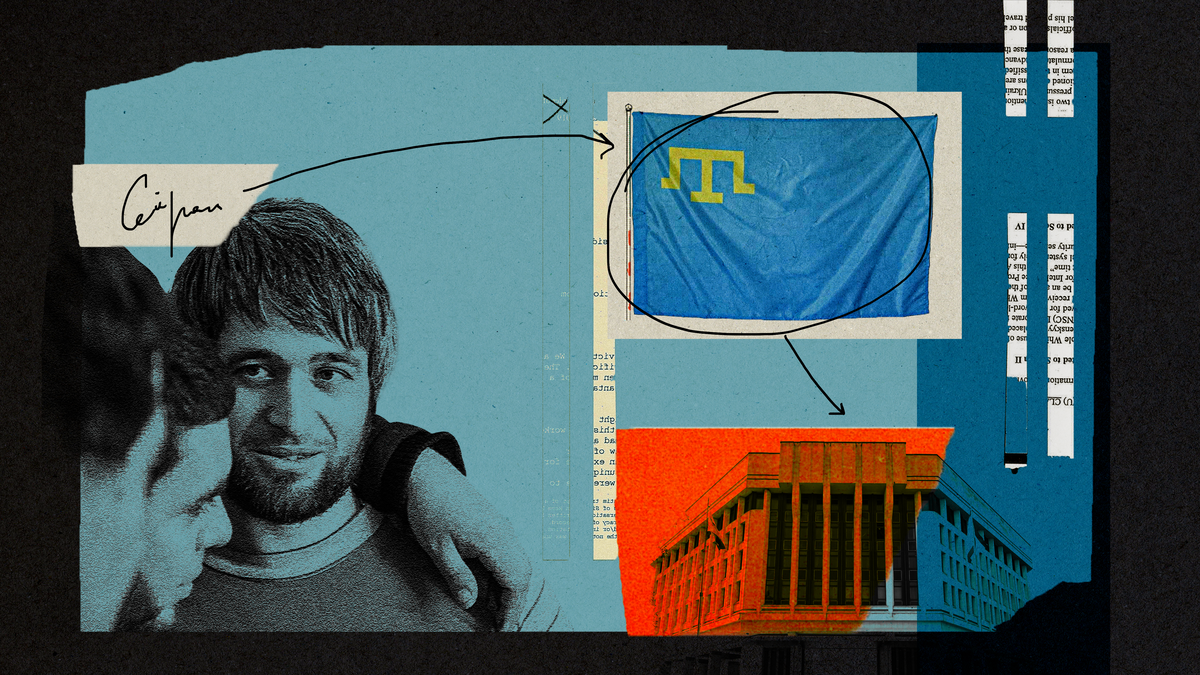

Seyran Saliyev is a Crimean Tatar activist and citizen journalist; a political prisoner.

He was born in 1985 in Abinsk, Krasnodar Krai, Russia. His mother, Zodiye Saliyeva, is a veteran advocate of the Crimean Tatar national movement for the return of their people to their homeland. Saliyev was seven years old when his family resettled in Crimea.

In 2003, he enrolled in the Simferopol Higher Vocation School to train as a PC operator. He holds an undergraduate degree in Turkish and Crimean Tatar languages.

Saliyev worked in trade and as a tour guide while actively volunteering and engaging in public activism. He taught Arabic and the fundamentals of religion and history to children.

Following the occupation of Crimea and subsequent persecutions, Saliyev turned to citizen journalism, documenting the persecutions of Crimean Tatars. In 2017, he was arrested under accusations of involvement with Hizb ut-Tahrir, an Islamic political organization banned in Russia, but not in Ukraine. In 2020, the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don sentenced Saliyev to sixteen years in prison for “participating in the activities of a terrorist organization”; “preparing for actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power or the forcible retention of power”; and “public calls for terrorist activities.” His sentence was later reduced by one year.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

In Seyran Saliyev’s house, tucked away in a dark corner of a closet, sits a black watch that no longer keeps time.

This watch is special. It’s designed for a practicing Muslim, reminding its owner of prayer times five times a day. It’s waterproof, allowing ritual washing before prayers without concern for water damage. And it’s stylish.

But the most special thing about this watch is that Saliyev purchased it during the happiest days of his marriage.

This was in the summer of 2017. By then, Saliyev had already come under the scrutiny of Russian law enforcement, experiencing an arrest and several searches. He realized time was running short. So, he and his wife, Mumine, decided to fulfill one of her most cherished dreams—a pilgrimage to Mecca.

The decision wasn’t easy: their youngest child, Safiye, had just turned three months old.

Mumine turned to her parents. Would they be willing to care for their four children while the couple embarked on a pilgrimage that every Muslim must make at least once in their life? “You must be crazy,” their parents said. “Wait another year, at least. We’re not ready to take responsibility for an infant.”

Then Mumine turned to her mother-in-law, Zodiye Saliyeva. Hearing her question, Saliyeva nodded hesitantly.

And so it happened that in the summer of 2017, the Saliyevs went on their first trip abroad.

“Seyran is a homebody,” Mumine says. “It was always a challenge to get him outside Crimea. A few times, I suggested traveling to Spain. But he’d be like, oh no, we’re building a house, we can’t go. And now, we traveled to a different, wonderful world—free from sin and evil—a place where dreams come true. The energy I felt during those days still nourishes me.”

It was during that Hajj that Saliyev bought a stylish black watch that reminded its owner of prayer times.

Three weeks after Saliyev returned home, he was arrested. Before Russian security men were set to detain him, he said goodbye to his wife and took off his watch, handing it to Mumine.

That day, the Saliyevs’ apartment was filled with people. Friends and strangers alike came from all across Crimea to support the wife of a recently arrested man. They lingered until night fell. Once alone with her thoughts, Mumine sat on the bed and picked up her husband’s watch, only to find that it had stopped.

A young man in a cool T-shirt

They met at the Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University. Mumine, a fourth-year student, was talking to her friends in the lobby when one of them said, “Look at that guy. See? He’s a practicing Muslim. He lives in our dorm.”

Mumine turned around and met the gaze of a young man in a cool T-shirt and jeans, his hair styled with gel. She didn’t expect a practicing Muslim to look like that.

From then on, Saliyev often lingered in the hallway to see her. One day, he mustered the courage to approach her and introduce himself.

They wanted to get married while Mumine was still in her fourth year of college. But her parents insisted, “You can see and get to know each other better, but marriage is out of the question until you graduate.”

Fast-forward eighteen months. At the end of August 2006, Mumine received her diploma. That very evening, Saliyev and his mother visited his sweetheart’s parents.

“Well, that’s it. We did as you wished, and now we want to get married,” Saliyev said.

“That’s right,” his mother confirmed. “We can plan a wedding in six months, in the spring.”

“In the spring, we’re planting potatoes,” Mumine’s father remarked. “Let’s plan for the summer.”

A wedding is always a significant occasion, especially one with a few hundred guests, as is traditional with Crimean Tatars. Weddings are planned months in advance.

“My son was twenty-one. No degree, no job, no place of his own… and talking about a wedding? I could hardly imagine that,” Zodiye Saliyeva recollects.

Saliyev and Mumine got married a week after they delivered an ultimatum to their parents.

Three hundred guests gathered in a huge tent not far from the mosque. The bride wore a red dress. They danced the night away.

Saliyev studied languages, but Mumine never received romantic messages from him before the wedding.

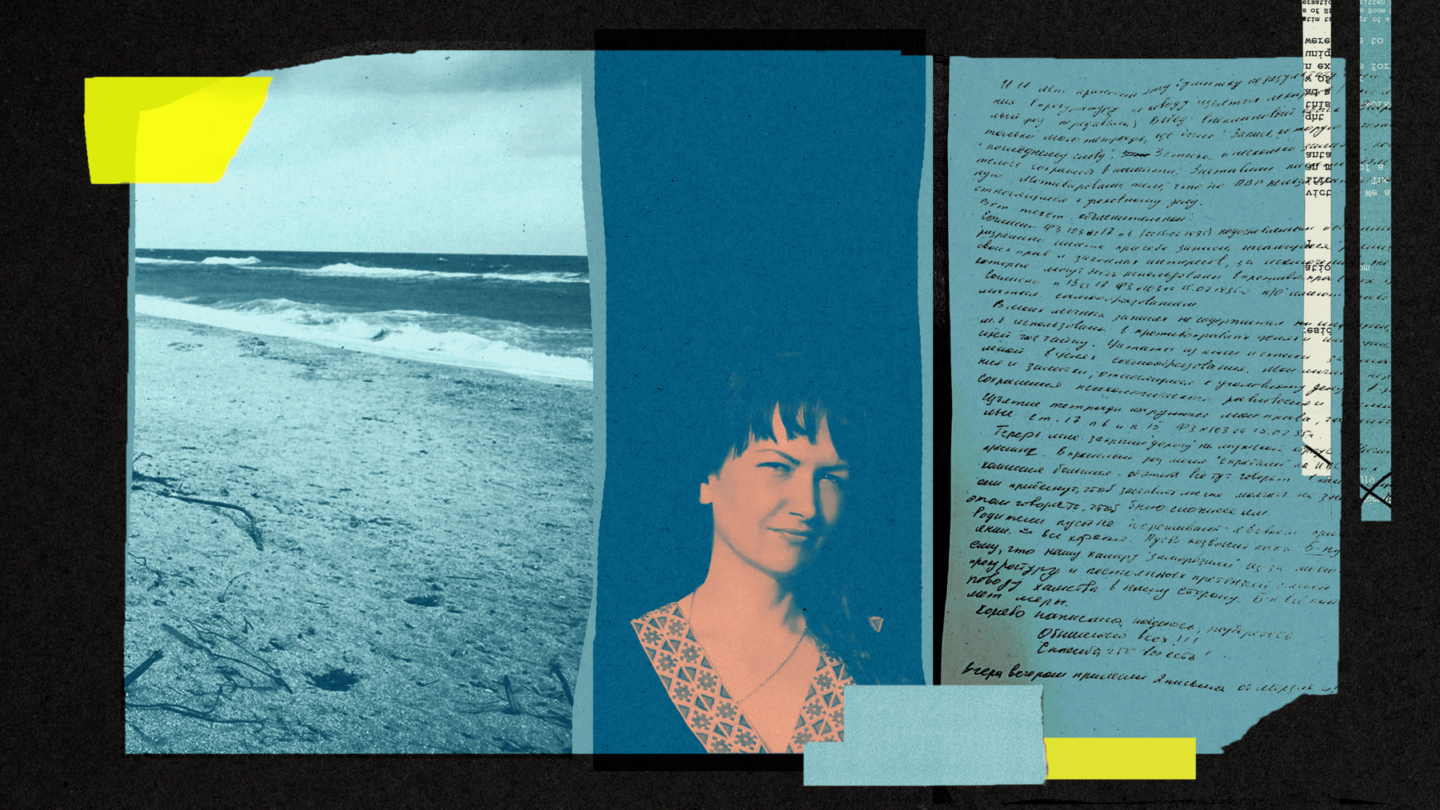

“Peace, mercy, blessing, and good patience of the Almighty to you, my life partner. May the Almighty be satisfied with you in all respects,” he would write to her from behind prison bars years later.

“I never saw him writing letters. Before we got married, I received only one romantic message from him—three sentences long,” says Mumine. “And now, Seyran walks into the visitation room with a black backpack stuffed with letters. ‘This letter,’ he tells me, ‘is to the ambassador; this one to my mentor; that one to my people; and these two to neighbors and family.’ It’s as if he’s trying to support everyone from inside the prison so they don’t lose hope.”

“Things just won’t happen there without me”

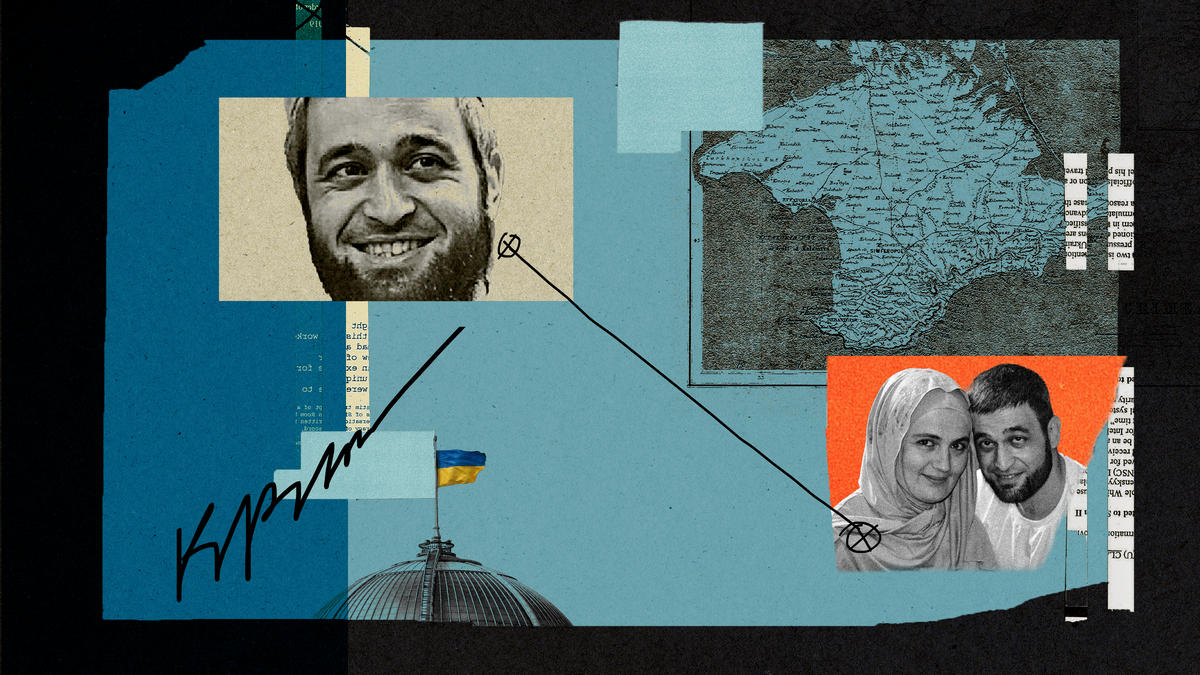

Saliyev found himself at his first protest campaign when he was only seven months old. Things like this happen when your mother is an activist in the Crimean Tatar national movement advocating for the return of her people to their homeland.

“That day, fellow activists and I marched to the district executive committee to voice our demands,” Zodiye Saliyeva says. “I held Seyran in my arms because I didn’t have anyone to babysit him.”

When Seyran was eighteen months old, his mother left him with her parents for a few weeks and traveled from Krasnodar Krai to Moscow. In 1987, Crimean Tatars organized a series of mass protest campaigns, including one on Red Square. “Things just won’t happen there without me,” Zodiye told her parents, explaining her intention.

Her son, Seyran, inherited his mother’s confidence that things just wouldn’t happen without his involvement.

Civic activity is a significant part of his life. He volunteered to help sick children. Helped organize religious and national holidays. Sat on judging panels during the tournaments in kuresh, Crimean Tatar national wrestling. Taught Arabic and the fundamentals of religion and history to children.

After the occupation of Crimea, searches in Crimean Tatar homes and trials based on fabricated accusations would become a new reality. Saliyev would go to the courthouse to support his people. He would become a citizen journalist.

He first confronted the Russian machinery of repression on May 12, 2016. That day, Russians conducted mass searches of Crimean Tatar homes in Bakhchysarai. Saliyev rushed to catch the bus as soon as he heard about it.

Today, sending a message in a group chat is enough to alert your community to the misfortune that knocked on its members’ doors. Back then, these chats did not exist, so Saliyev went to the mosque to alert his people.

A loudspeaker on top of the minaret amplified the call to prayer made at the appropriate hours. This time, it amplified Saliyev’s voice as he informed the community about the addresses of house searches so that people could go and support their fellow citizens.

The occupation court classified Saliyev’s actions as organizing an unauthorized rally and fined him twenty thousand rubles.

Saliyev would not be intimidated, though. He continued to actively support Crimean Tatars persecuted by Russia.

In January 2017, Saliyev’s three children first saw armed men in balaclavas in their own home.

“On January 20, they discharged me from the hospital. I was pregnant with our fourth child, and the pregnancy was complicated,” Mumine recalls. “I remember that on January 27, there was a snowstorm. It was bitterly cold. When they started pounding on the door at five in the morning, I immediately knew who it was. There were riot police, police trucks, and even dogs. And they only brought dogs on particular occasions.”

They searched the Saliyevs’ apartment and led the head of the household outside in handcuffs. The court sentenced him to twelve days in detention for posting a song by Chechen bard Timur Mutsurayev, which was banned in Russia, on his page in social media. The judge ignored the fact that Saliyev had actually posted the song before Crimea was occupied.

After the detention, Saliyev realized that if he and his wife didn’t perform Hajj as soon as possible, they wouldn’t be able to do it later, at least not for a long while.

And he proved to be right.

On October 11, 2017, Saliyev and five other Crimean Tatars were arrested. They were accused of participating in the activities of a terrorist organization and preparing for the forcible seizure of power.

In 2020, the Russian court sentenced Saliyev to seventeen years in prison.

To change your environment before it changes you

It takes 1,500 kilometers and two days of “living” on a series of trains to get from Bakhchysarai to the penal colony in the Tula region where Saliyev is being held.

In March 2024, Mumine made this trek with her four children: Salikh, Samiya, Suriye, and the youngest, Safiye. It wasn’t her first trip to see her husband, and she felt anxious before each one. However, the nature of her anxieties differed significantly each time.

When Mumine traveled there for the first time, she was worried that five years in isolation, surrounded by actual criminals, might have profoundly affected her husband. “What would he be like?” she wondered. “What if his ideas had changed? What if he would speak to me using prison slang?”

During her most recent trip, she had a different concern: What if they traveled all the way to the Tula region only to be told that the administration of the penal colony would not allow Saliyev’s family to see him? Mumine is no longer worried that prison might turn her husband into a different person.

When they saw each other in the spring of 2024, Saliyev was staying in the same barrack with ninety-seven prisoners. He was the only political prisoner; the others were imprisoned for drug dealing. It was in this environment that Saliyev tried to maintain his dignity, good health, and convictions.

In a letter to his wife, he shared a story about a walk. On a winter day, Saliyev and three fellow inmates were taken for a walk in the courtyard. Seeing that the yard was full of puddles, Saliyev demanded that the guard take them to a different place where they wouldn’t have to slosh through water. “There are puddles in all yards,” the guard claimed. But Saliyev wouldn’t budge.

The guard took them to another yard. However, it was also full of puddles. Saliyev voiced his demands again. Only then did the guard take them to a dry yard.

“Suddenly, the guard asked me, ‘Are you from Crimea by any chance?’” Saliyev wrote in his letter. “And I said that yes, I’m from Crimea. And then he said, ‘That’s what I thought,’ meaning that in this prison, only Crimean people were so demanding and refused to keep silent.”

“He didn’t betray his principles,” Mumine says, talking about her husband. “Seyran continues to live the life he lived on the outside. He knows that the group influences the individual. So, he’s trying to change the group.”

Holiday at the stadium

February 7, 2017, marked a true holiday for the Saliyev family. Their apartment and the communal hallway were decorated with balloons and Saliyev’s photos. In the yard, pilaf cooked in a cauldron over an open fire while tables brimmed with treats. Crimean Tatar music filled the air. That day, hundreds of friends, acquaintances, and supporters of their cause arrived at the family’s doorstep.

The reason? Saliyev had returned home after an administrative arrest, having spent twelve days behind bars.

Everyone wanted to hug him, shake his hand, and offer words of support. Saliyev couldn’t resist dancing that night. He later confided to his wife that he had never expected such a warm welcome.

In their letters, other Crimean Tatar political prisoners, still incarcerated at the time, expressed hope that people awaited their return and one day would welcome them back as warmly as they did Saliyev.

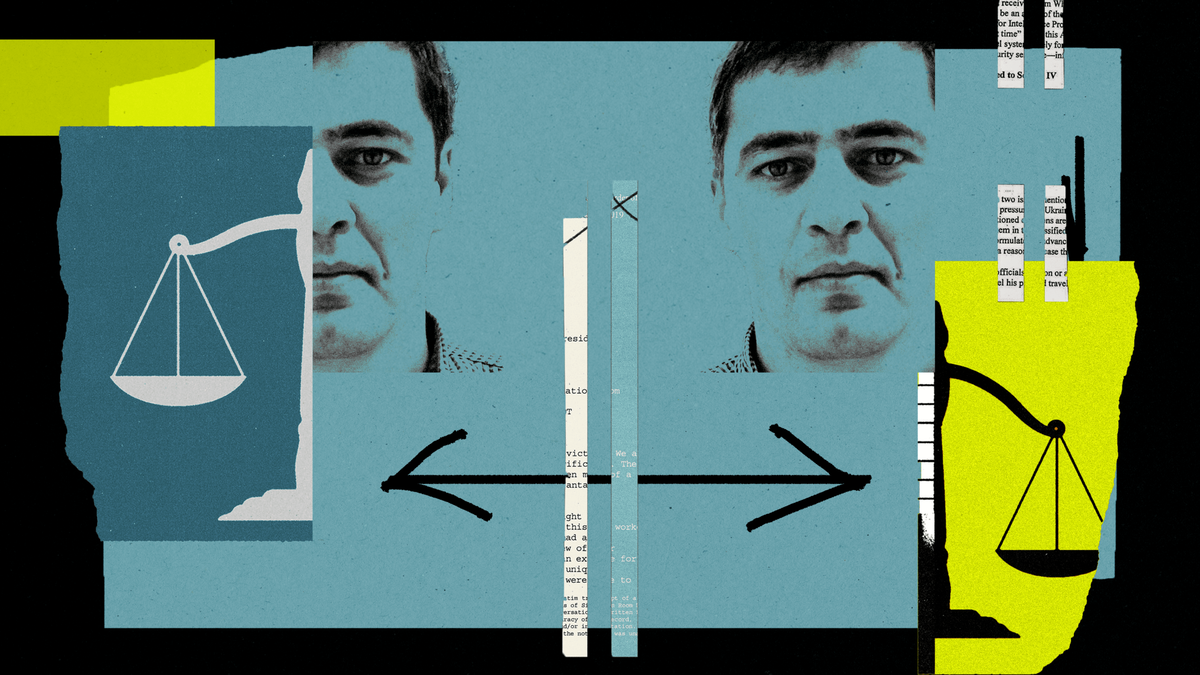

In 2022, the court of appeal reviewed Saliyev’s case and reduced his sentence by one year. The Russian judiciary won’t release Saliyev until 2032.

Mumine Saliyeva dreams of an earlier release for her husband. She also dreams of the day when all Crimean political prisoners will be freed.

“This will be a great holiday for all of Crimea,” she says. “It will go down in history. We’ll rent a huge stadium in Bakhchysarai because none of us, the wives of political prisoners, can imagine welcoming our husbands alone.”

This text was written in April–May 2024

Translated by Hanna Leliv

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано ілюстрацію Марії Глушко, а також світлини з родинного архіву, Кримської солідарності й Антона Наумлюка.