“I heard how they were dying. My husband was breathing hard, straining, as if trying to lift a slab off himself, but he couldn’t manage to do it. Then, one second, he just stopped moving. My grandmother and Zhenia died instantly. I heard my daughter cry. In a moment, she fell silent, too. My mother told me that my son called out my name several times before falling silent.”

This is a testimony of Svitlana Zheldak, who lost her entire family after a Russian missile struck her house in Chernihiv. It is one of the tens of thousands of stories documented by journalists, human rights activists, international organizations, and law enforcement officials.

I document war crimes and crimes against humanity in this war that Russia began in 2014. At that time, Ukraine got a chance for democratic transformation after the Revolution of Dignity had resulted in the fall of the authoritarian regime. To stop us on this path, Russia occupied Crimea, parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and, last year, launched a full-scale invasion. Because Putin is not afraid of NATO—Putin is afraid of the idea of freedom.

Following February 24, 2022, we faced an unprecedented number of war crimes. Russian forces deliberately destroy residential buildings, churches, schools, hospitals, shell evacuation corridors, maintain a system of filtration camps, carry out forced deportations, erase Ukrainian identity, kidnap, rape, torture, and kill people in the occupied territories.

This is a deliberate policy. Russia uses war crimes as a method of warfare. Russia aims to break resistance and occupy the country through the unspeakable suffering of the civilian population. That is why we are documenting not just violations of the Geneva and Hague Conventions. We are documenting human suffering. Through the joint efforts of the Tribunal for Putin initiative, we have documented about 50,000 instances of war crimes.

I have spoken with a hundred people who survived captivity. They told me how they were beaten, raped, suffered electric shock to their genitals, had their nails pulled out, knees drilled into, and were forced to write with their blood. One woman told me how they gouged out her eye with a spoon.

Our mobile teams found bodies of civilians on the streets and in the yards of their houses following the liberation of Bucha. These people were not armed at all.

There is no justification for Russia’s actions. There was no military necessity for this. Russians did this simply because they could.

I ask myself: for whom are we documenting all of this?

Ukraine’s legal system is overloaded with the number of ongoing investigations. The International Criminal Court will limit itself to investigating a few selected cases and has no jurisdiction over the crime of aggression in the case of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. There is an evident gap in accountability.

Then who will give all the victims of this war a chance for justice?

I work with people who have endured hell, and I know for certain that, besides their shattered lives, families, and visions of the future, these people need a restoration of faith that justice exists. Even if it is delayed in time.

And this is important not only for Ukraine.

Because this is not a war between two countries but a war between two systems— authoritarianism and democracy. Russia wants to prove that democracy, the rule of law, and human rights are false values. If they are genuine, why can’t they protect anyone? Why is the entire UN system still unable to stop Russian atrocities? Why do I, a human rights defender who has used the law to protect people for many years, now have to answer the question of how to help people survive in occupied territories with—“Give modern weapons to Ukraine”?

Because the law doesn’t work right now. But I believe that this is temporary.

In the 20th century, the civilized world took a significant step towards asserting justice and the rule of law. War criminals of the Nazi regime that had fallenwere convicted at the Nuremberg Trials.

In the 21st century, we must go further. Justice should not depend on the strength of the Russian regime. Justice should not wait. We need to establish a special tribunal for the crime of aggression now and hold Putin, Lukashenko, and others responsible for this crimeaccountable.

Yes, this is a bold step. And it must be done because it is the right thing to do.

One of the most critical questions posed by the current Russo-Ukrainian war is how we will protect the human being, their dignity, their rights, and their freedom in the 21st century.

Одне з найголовніших питань, яке ставить нинішня російсько-українська війна, — це як ми у 21 столітті будемо захищати людину, її гідність, її права та свободу.

Can we rely on the law, or will only weapons matter?

Russia is trying to demonstrate that a state with significant military potential and a nuclear arsenal can dictate its rules to the entire international community and even alter internationally recognized borders. If this problem is not resolved, and the international rule of law is not restored in the near future, it will have long-lasting negative consequences for the development of the world. Governments will invest in weaponry rather than education, science, healthcare, social protection, and addressing global challenges like climate change, social inequality, poverty, etc. New technologies provide ample room for experimenting with weapons of mass destruction and creating robot armies. In such a world, everyone, with no exception, will be in danger.

Therefore, the values of modern civilization must be defended.

The world has grown accustomed to conceding to dictatorships. Developed democracies have forgotten that states that kill journalists, imprison activists, or suppress peaceful demonstrations pose a threat not only to their own citizens but to the entire region and world peace. This is how impunity for the Kremlin’s destruction of Grozny in Chechnya, populated by over half a million people, leads to massive Russian bombardments in Aleppo, Syria, and eventually to Mariupol, Ukraine, obliterated by artillery barrages.

Current international law defines international crimes as those that threaten the existence of all humanity as a species. Because it is precisely impunity that encourages the repetition of such crimes in other parts of the planet. The world must demonstrate through concrete actions that those who commit these crimes will not hide behind an abstract Putin, and sooner or later, they will be held accountable. This will have an immediate deterrent effect on other dictators and on the level of brutality of crimes that Russians commit in Ukraine daily. In the context of a full-scale war, it means that we can save human lives.

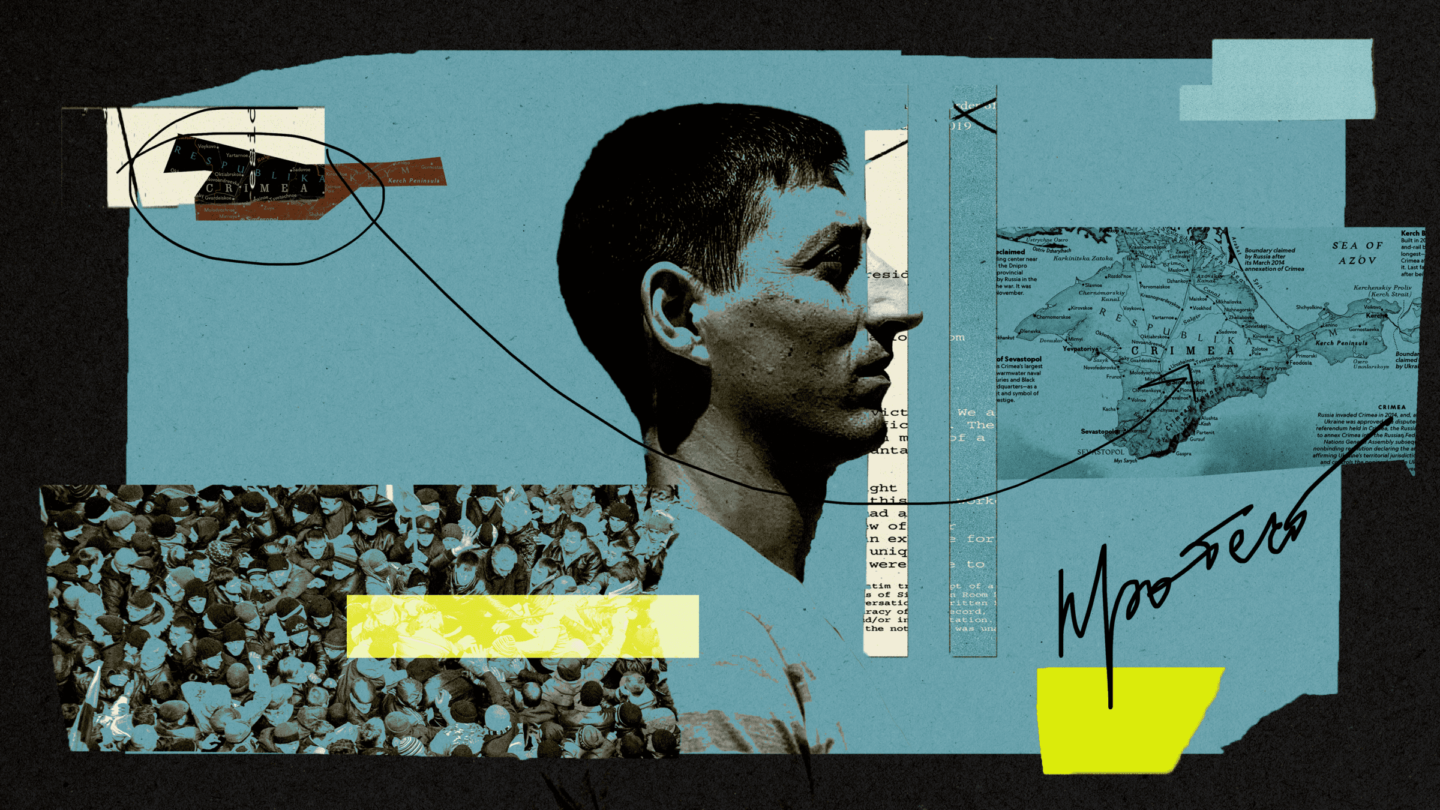

Meanwhile, war turns people into numbers. The scale of international crimes is so vast that we cannot tell all the stories. But let me tell you one.

Shortly after the start of the full-scale invasion, 62-year-old civilian Oleksandr Shelipov was killed by Russian soldiers near his own house. The tragedy gained widespread attention in the media only because it was the first trial of Russian war criminals since February 24. During the trial, Shelipov’s wife said that her husband may have been an ordinary farmer, but he was her whole world, and now she has lost everything.

People are not numbers. We must give people their names back. We must ensure justice for all victims of international crimes, regardless of who they are, their social status, the type of crime, and the severity of the suffering they endured, regardless of whether the media and society are interested in their case. Because every human life matters.

New technologies provide opportunities to document war crimes that we couldn’t even dream of just fifteenyears ago. Ordinary people have access to various digital tools: Google Street Maps helps identify locations, while Google Lens allows searching for similar images online. There are resources for checking metadata, for determining where and when a video was first posted, and much more. After all, many photos and videos have been taken over these months, and at least some of them will surely be available. Furthermore, the work of organizations like Bellingcat convincingly demonstrates that it is possible to reconstruct the sequence of events and identify war criminals, even without being present at the scene.

And yet, instead of improving the international criminal justice system, politicians continue to pit peace against justice. It is important to remember the lessons of history. On August 21, 2013, the Syrian government used chemical weapons in the suburbs of Damascus. Government forces bombarded the civilian population with rockets containing sarin, a nerve agent. Over 1,700 people were affected, many among them children.

Chemical weapons had been recognized as a red line, so the response from the international community was supposed to be inevitable. But the result was a political compromise. The Syrian government promised to join the Chemical Weapons Convention and destroy its existing stocks of sarin. Russia was supposed to guarantee the fulfillment of this promise. No one askedthe victims and human rights defenders for their opinion on the matter.

It’s easy to guess what happened next. Before Russia vetoed the renewal of the mandate of the Joint Investigative Mechanism of the United Nations and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, international experts had collected and presented evidence of at least four new chemical attacks against civilians.

Unpunished evil grows. The world must react to blatanthuman rights violations.

There will always be politicians who will argue for forgoing justice to save lives. But if we agree to that, there will be neither justice nor saved lives.

Ultimately, justice is the demand of millions of people in different countries around the world. We must change the global approach to justice for international crimes. Ukraine also seeks justice. A Ukrainian psychologist asked different people from whom they would like to hear an apology for Russia’s war against Ukraine—from Putin, Russian intelligentsia, the parliament, the Russian people, or specific individuals. The response she receive—“from no one.” Ukrainians do not need apologies. People need justice.

Sustainable peace that provides freedom from fear is impossible without justice. All these decades, Russian soldiers committed crimes in Chechnya, Moldova, Georgia, Mali, Libya, Syria and remained unpunished. They started to believe they could do whatever they wanted.

We have a chance to break this cycle of impunity. Not only for Ukrainians and other peoples who have already suffered from Russia’s actions. But also for nations that could become the next targets of Russian aggression. And this time, to prevent it from happening.

Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the Center for Civil Liberties, 2022 Nobel Peace Prize laureate

Цей текст створений завдяки системній читацькій підтримці. Приєднуйтеся до Спільноти The Ukrainians і допомагайте нам публікувати ще більше важливих і цікавих історій.

Якщо ви хотіли б поділитися своїми думками, ідеями чи досвідами і написати колонку, то надсилайте листа на емейл — [email protected]. Погляди, висловлені у матеріалі, можуть не співпадати з точкою зору The Ukrainians Media. Передрук тексту чи його частин дозволений лише з письмової згоди редакції. Головне зображення — Вадим Блонський.