[This interview was made possible thanks to the support of The Ukrainians Media community. Join to help us keep creating meaningful content.]

§§§

Sumy has always had a habit of waking up early. Perhaps it’s rooted in its trading past — for centuries, the city was a crossroads with bustling markets and traders are known to start their days at dawn. Or maybe it stems from its manufacturing rhythm — early morning shifts at large factories trained the city to rise with the sun. We even used to have a curfew that lifted at 4:00 a.m., while in the capital, residents couldn’t begin their day until 5:00 a.m..

A mere year ago, we didn’t feel comfortable calling ourselves a frontline city. However, the shifts in the frontline and an increased military presence in the city have changed that. These days, we are more comfortable seeing cars with triangular AFU markings than clinging to an illusory “peaceful” life. This may be due to our trauma from the beginning of the full-scale war, when on the morning of February 24, we found ourselves with no military or law enforcement forces. It’s easier to live side by side with the military and do what we can for our common cause.

Sumy isn’t the typical frontline city you see on the news. Even now, we have waterfront walkways where crowds of people stroll every day, a historical center with coffee shops that serve excellent coffee, parks and revitalized courtyards that still host festivals and concerts. War didn’t erase this vibe — it amplified it.

No matter how we define our city during the war, mornings here begin, if you can believe it, just like anywhere else. We brew the tastiest coffee, take a moment to appreciate another new day, admire the cuteness of our pets and say our “I love yous” bright and early.

It seems the war has taught us to live one day at a time. This is not how we wanted it to be, but it does help us focus on the moments that truly matter. This morning rhythm fully reveals the city’s character.

Our friends run a local coffee shop, and they never closed, even when they were barely breaking even. Only the rumours of a new potential enemy advance had the power to stop people from going out — nobody left the city, but people froze, trying to process it all. Business owners say that if they close, people would take it as a red flag and start leaving the city. So they persevere, reinvent themselves and preserve at least some normalcy for the residents. The challenges that business owners face are not always visible to the public. Local businesses are forced to adapt, improve, become “sexier” to stay competitive and modern, especially in the conditions of a struggling economy. Another friend said, “I want to bring Kyiv to Sumy.” I reckon, by now, we’ve got a few things we could bring to Kyiv.

However, not everyone is able to adapt to the new reality. Some businesses shut down quietly — one day, their names simply vanish from the storefronts or fade in the sunlight.

Our morning rhythm gives us a tangible advantage. While hundreds of our friends in the capital are still transferring between subway lines, we’re already finishing our second cups of coffee with colleagues, and by 9 a.m., sometimes even 8 a.m., we’re ready to work. This early start gives us an extra buffer in case a strike occurs during the day. If there is a strike and you are not directly affected, you can use that extra time to help out with clearing the rubble or aiding the victims. Sumy natives are so interconnected that there is a big possibility that a friend of a friend will need help replacing their windows or paying hospital bills.

If the day hasn’t been interrupted by a strike, you may treat yourself to a nice lunch break. If you have a car, you can grab your food and, regardless of where you are in the city, drive just ten minutes to reach one of the beautiful forests surrounding Sumy. During the pandemic, we rediscovered these nature spots as places for recreation and renewal, and they still serve that purpose now, even as the sounds of explosions echo in the distance.

Sumy will have to reinvent itself. Thousands of people and dozens of businesses have disappeared from the city’s landscape.

Our last ties to Russia were, hopefully, severed in 2022, and the businesses that once depended on its market have now completely lost their value. Many of them can’t be modernized to meet Western standards — they were simply too outdated and oriented toward post-Soviet Russian industry.

For our city, a future as a military hub is far from ideal. Nowadays, we simply must adapt, and we’ve been doing a good job of it so far. However, we’d like to envision something more ambitious, though undoubtedly founded in security — we have to be realistic about our proximity to the horde.

And so, here we are, caught between contrasts — abandoned factories and new-wave coffee shops, contemplating: What will we become in five or ten years?

A city of small businesses? Medical tourism? Agriculture? A student city? Which spot will our city take on the socioeconomic map of this country and the world?

We are sensitive and on edge, tense and ready to go. “All money should go towards buying drones” is a comment that appears under any post contemplating Sumy’s future. But if we don’t find a dream worth living and working for in this city, we will run out of money very quickly and won’t be able to buy anything at all.

Many businesses, for a variety of reasons, have either moved out of Sumy or shut down entirely. Some, in the process of relocating, discovered new markets and made the most of state support or international aid programs. Others have lost people, and some don’t have anything left to move. The destruction of a business affects hundreds, even thousands of people and families that work for that business — it’s never about just one fishmonger or small manufacturer.

New businesses that have sprung up during the full-scale war have become the testing ground for experimentation, research and dreams for the future of our city. In the past three years, Sumy got a new wine bar with tastings, a private museum, a gallery-cafe, bakeries, multiple restaurants and a craft cocktail bar, while many existing cafes started offering breakfasts. The older eateries haven’t stopped evolving either — they rebrand, refresh and seek new opportunities to grow in the current challenging environment. We’ve also witnessed a boom in businesses offering water-based leisure activities, so much so that traffic jams of paddleboards and catamarans on the Psel River have now become a routine occurrence.

Despite many risks, new businesses focused on developing and manufacturing military equipment are also emerging. For obvious reasons, we have to keep the details to ourselves.

As long as we have the strength and ambition to open new cafes, build factories, develop fresh brands, we will have the time to define who we are and decide what we’ll be doing next and why.

Living in Sumy is both a protest and a manifesto. In May 2022, I left the oblast for the first time since the invasion, and when I came back, I proposed to my colleagues that we revitalize the Yard on Kuznechna and repair the pavement on the playground there. At first glance, that decision seemed irrational — only a few months had passed since the Russian forces were driven out of the Sumy Oblast. Yet it was a manifestation of our inner protest and affirmation that we’re here to stay and won’t give up anything.

I’ll never forget how excited we were about the upcoming summer and seeing our friends at various open-air events. If in 2022 hundreds of people attended standup gigs, concerts and lectures as a way to reflect on what they’ve been through, in the following years we witnessed the emergence of a new generation of people who craved normalcy amid the uncertainty and wanted to realize their potential here, contribute to the community and take part in the shaping of a new future.

In the fight for our city, every project and volunteer initiative serves the common good. But there’s also a personal aspect: we’re rebuilding relationships with our loved ones. Some no longer have friends in the city; the luckier ones can visit their friends in Kyiv or elsewhere in Ukraine, although often these visits are impossible due to a lack of time or border restrictions. Some seek out new connections, and some manage to preserve their existing friendships long-distance.

People seek firm ground beneath their feet and a feeling of support from their city. They try to keep the streets well-cared for and criticise those who undercut this effort.

It may seem strange to be concerned with architecture when it could be destroyed at any moment. But our love for what is ours and our faith in being able to keep it encourage us to combine wartime necessities with our usual human needs.

Some enlisted and made sure they were stationed on the Sumy border. Others have been volunteering for four years straight, somehow finding ways to keep going after yet another burnout. A few days after a shelling, people plant flowers in spots that have only just been cleared of rubble. Retirees get together to weave camouflage nets, and young parents organize children’s entertainment in bomb shelters. Electric utility crews head to work like sappers — uncertain if they’ll return from a repair job.

Our daytime struggle for normalcy ends with dusk. Then a new struggle begins — against fear, against the sky, against silence. Like trained animals, we instinctively reach for our phones before bed, scrolling through Telegram channels, often falling asleep with phones in hand.

At night, we don’t breathe. It feels like breathing could drown out the sound of an approaching Shahed drone. The scariest sound is that distinctive whirr it makes when it goes in for its target.

If the city has already been attacked today, the brain convinces you that tomorrow is more likely to be peaceful. It’s harder to fall asleep when you’re expecting an attack, when every sound outside the window can mean the beginning of the end. Yet, even this nighttime silence has its own survival logic Sumy dies each night, but it springs back to life early, giving itself more time and filling its struggle for freedom with new meaning.

Dmytro Tishchenko, the founder and head of the public organization Cukr.city, which specializes in media, cultural and educational activities.

If you would like to share your thoughts, ideas, or experiences by writing a column, please email us at [email protected]. The views expressed in this material may not reflect the position of The Ukrainians Media. Reprinting this text or any part of it is permitted only with the prior written consent of the editorial team.

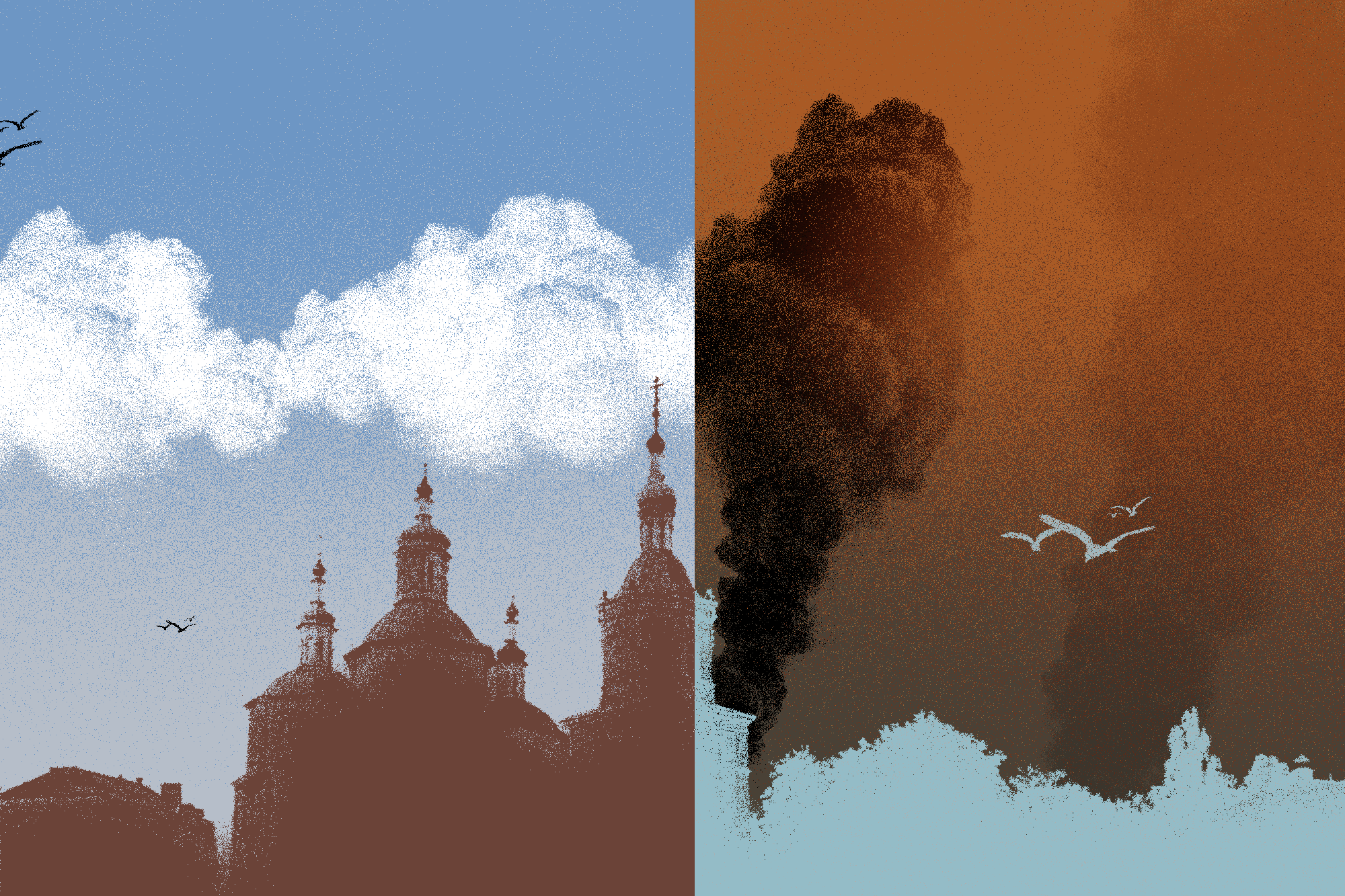

Illustration by Vadym Blonsky

Translated from the Ukrainian by Liubov Kukharenko