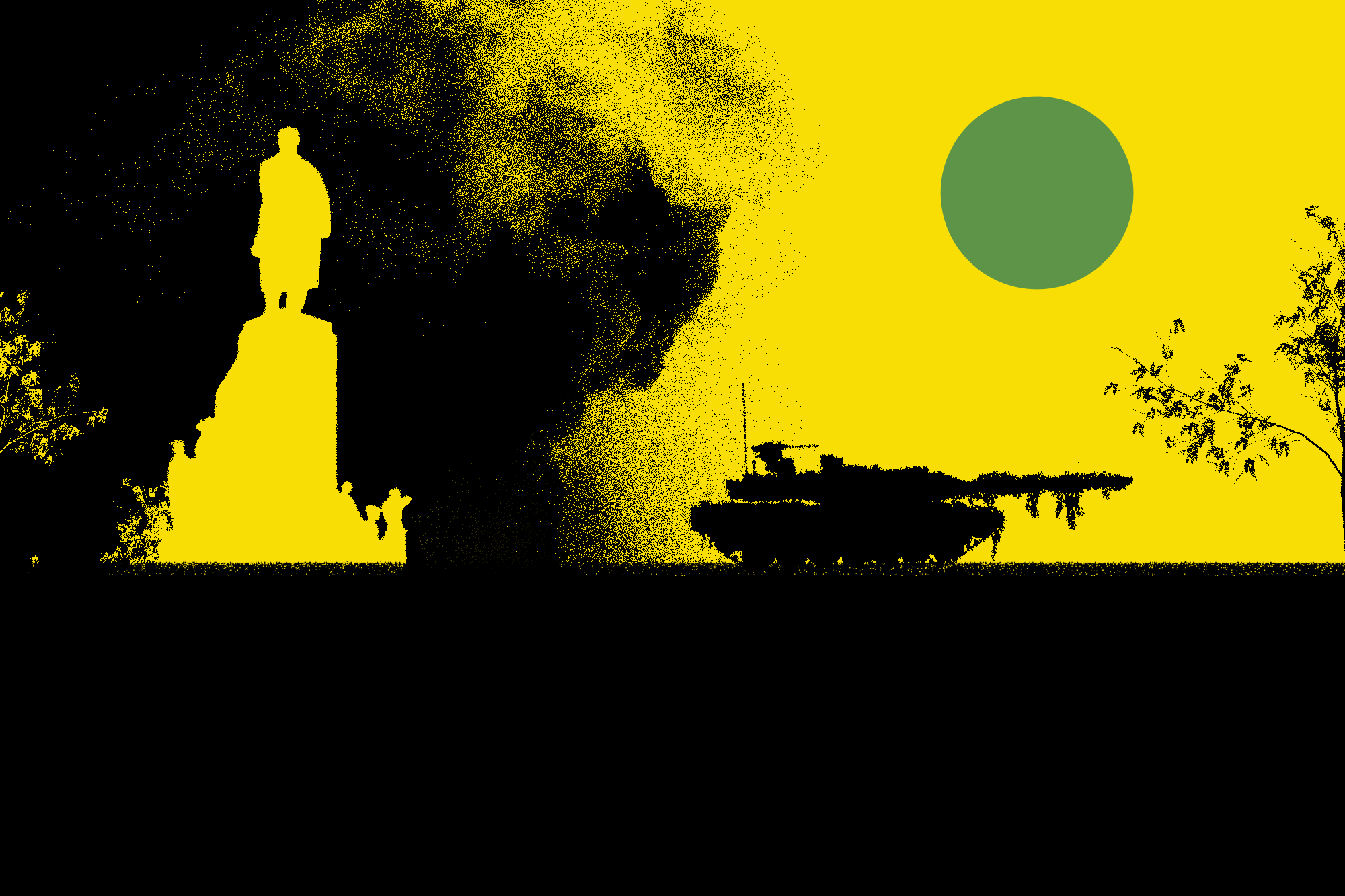

Reflecting on the changes of the past decade, we asked writers to share how their cities have transformed. Serhiy Zhadan writes about Kharkiv’s residents, who persistently cling to signs of peaceful life.

Early April in the city feels gentle and light. Overnight, colors and the atmosphere shift. Trees that appeared bleak and black in wintery sadness just yesterday now bloom in the morning light; fresh greenery emerges from nowhere, and spring fills the air, transforming everything urgently and completely. The streets, dusty and open, fill with young people who seem to have a bit too much free time, lounging around dry fountains, while locals go about their daily routines. Sunlight grows stronger, winter fades irrevocably into the past, and the warmth feels endless.

In the evening, when it darkens, the streets empty quickly. Cafés and shops close by nine. After that, doors remain open, but nothing is operational. Staff linger, tidying up, reluctant to leave—there are still two hours until curfew, and the evening lights make the dusk feel sweet and mysterious. The last few pedestrians move through the city, lighting their way with flashlights; some walk their dogs, others hurry home. No one walks without reason—roaming dark sidewalks with a flashlight isn’t much fun. Gradually, the city goes still; the streets stand silent and empty. Sometimes, the quiet is shattered by a military vehicle speeding through the night. Then, the city falls silent again, and its residents dream their April dreams. The shelling usually begins near dawn.

Spring 2024 marks the third year of the full-scale invasion, ten years of war. In spring 2014, ten years ago, Kharkiv was also unsettled. Maidan that ended with an attempted “congress of South-Eastern deputies” in the city, the flight of the president and local government, tensions between pro- and anti-Maidan groups, the brutal clashes on March 1 involving “tourists” from Russia, and attempts to destabilize the city. All of this played out against the backdrop of Crimea’s annexation and the emergence of Russian militants in Donbas. I remember that evening when separatists seized Kharkiv’s regional administration building. Darkness came uncomfortably close, blanketing the central districts. But the building was cleared, and the city remained under Ukrainian flags. Crimea stayed in occupation. The war was localized in Donbas, and Kharkiv continued its peaceful life. The war didn’t reach here. The war happened elsewhere.

What was that peaceful life like? How did the city live before February 24, 2022? It had a strange, transitory status, both literally and figuratively. Passengers disembarked at the railway station and continued on their routes: soldiers heading to the front lines, civilians taking taxis to cross the border into Belgorod, Russia—as there was no fighting in that direction, it was possible to cross the border freely, to pretend that life was going on as usual, that nothing had changed, just some inconveniences that could be managed. Something similar happened in the city’s political life: local authorities, holding onto regional distinctions and unique electoral dynamics until the last moment, played party games and clung to denial, ignoring the unavoidable—the presence, just forty kilometers away, of an enemy who didn’t care about local specifics, who didn’t care about borderland status, only about annexation and assimilation. On the morning of February 24, that’s what happened.

In fact, February 24, 2022, marked a radical shift. A full-scale war had begun, affecting everyone and impossible to ignore—a strike could hit anywhere, harm anyone, regardless of political views or citizenship. Within a few days of the full-scale invasion, the city became unrecognizable: half-empty, heavily damaged, threatened and darkened, it barely resembled the metropolis it had been recently—with cranes filling the skyline, traffic jams and sales, crowds of young people on the streets, and a bustling metro.

Now, the metro stations were filled with people who had lost their homes and were sheltering from shelling, and the city itself lived an entirely different life, driven by the need to survive and a desire to endure.

More than two years into full-scale war, life has yet to return to normal. In fact, the idea of normalcy feels overly abstract and distant. At times, it seems that the changes in the city are irreversible, that things will never be as they were. And yet, this question arises—have we all truly changed? Not in terms of windows covered in plywood or daily habits like watching for air raid sirens or adapting to power cuts, but in how we feel about this city, this country, this moment in time and space. We want to see change, to prevent the same mistakes, to ensure lessons are learned, dangers removed, and that the future doesn’t become a trap. But what do we have instead?

A weary, battered city, struck nearly daily by an enemy who cynically denies their hostility. Stressed and emotionally exhausted residents who stubbornly hold onto signs of peaceful life, restoring whatever semblance of normalcy they can, striving to preserve it amid constant shelling and blackouts. The complete breakdown of past communications and social ties, the population shuffled like a deck of cards—some have joined the fight, others are gone, some have left, some left and returned, and some would like to leave but have nowhere to go. In my opinion, it seems impossible to calculate any steady statistics on change or transformation in this situation. All we can do is document these daily individual, personal shifts, the breakdowns, and realizations—or their absence. Document them so that in the future, we don’t forget, so that we might try to understand what, exactly, was happening to us all this time, what changed in us, and what didn’t. After all, if we think about it, there’s a painful line somewhere here, a fragile realization—we’ve all changed, of course, in this bloody, turbulent whirlpool. Yet—and this is hard to deny—in many ways, we’ve remained ourselves, same as we had been, with our memories, our past. So, how do we live with our past in the future? What do we do with it there? And—with such a past, is any future even possible?

Sometimes it feels like here, in the east, near the border, we spent the last ten years carelessly leaving the door ajar, paying little mind to the constant draft and the voices outside. Now, instead of a border, there’s a front line. The front holds. But the draft doesn’t go away.

Illustration — Vadym Blonskyi

Translation — Iryna Chalapchii

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]