When the war in Ukraine ends, the territories are de-occupied, cities are liberated, and borders are restored, the battles will leave a dangerous legacy—mines. No country has ever faced such a large-scale mine problem. According to the State Emergency Service of Ukraine, over a quarter of Ukraine’s territory remains mine-contaminated.

This material is part of the project “The Most Mine-Contaminated Country in the World,” intended to show that behind the problem of mine-contaminated land, there are also tragic and heroic human stories.

It’s the third spring of the major war in Kharkiv Oblast, and children play tag joyfully on a village street. They leap from one wooden box to another. The boxes are still marked “Customer: Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation.” Before they became part of a children’s game, these boxes held BM-21 Grad shells that had bombarded the village.

Thirty-seven-year-old Oleksii Kostenko from Kharkiv resembles a kind Viking. One day, he accidentally witnessed this children’s game and couldn’t quite pinpoint what he felt.

“It’s hard to describe. Disgust is probably the closest word. It felt so unnatural and yet had become so normal for the children.”

When Oleksii reflects on why he became a deminer, he returns to this memory, this image of something that shouldn’t exist in a normal world.

In Ukraine, demining is coordinated by the national mine action center. State structures, such as the State Emergency Service of Ukraine and police bomb squads, work alongside non-governmental organizations. Forty-seven operators are now certified as mine action operators, with another fifty in line for certification, according to the Ministry of Economy. Still, it’s not enough. As of September 2024, the State Emergency Service reported 139,000 square kilometers of mine-contaminated area—roughly the size of Greece.

There aren’t enough deminers, and the mine-contaminated area only grows.

Oleksii dreams of seeing the country cleared of mines within this generation. That’s why he and others like him work every day, inch by inch, returning the land to the people.

Balancing Family and Duty

Oleksii Kostenko’s work is painstaking. Some days, he clears just twelve square meters; on other days, only one.

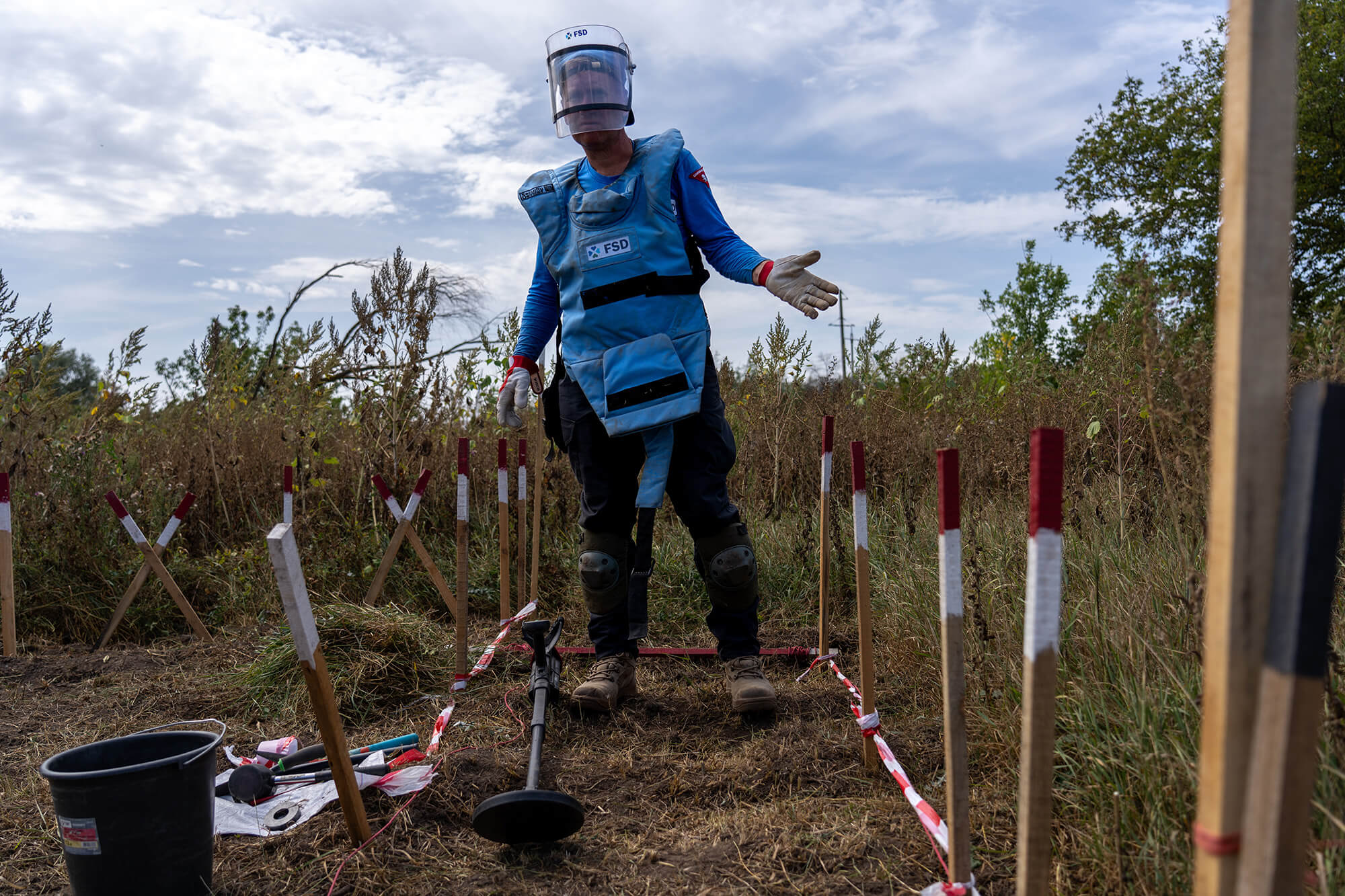

In Kharkiv Oblast, Oleksii kneels in dry grass between a narrow river and a field of overripe watermelons. Ahead lies a patch of land marked with red and white stakes—his section for today. He wears a blue vest from the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD) and red gloves. He works methodically and without any hurry, following protocol: visual inspection, cutting grass, manual checks, and only then a metal detector sweep. Many times on a loop. This is manual demining—slow, meticulous, reliable. His metal detector often beeps; the land is heavily contaminated.

“There was fierce fighting here, everything imaginable flew. So we find everything from bullets to fragments of BM-27 Uragan.”

Oleksiy has two higher degrees, he once worked as a teacher before opening his own auto repair shop in Kharkiv. After the full-scale invasion, he felt a need to be useful.

“It was high time for me to see that I wasn’t in the right place and wasn’t doing the right thing. Around that time, I saw an ad for deminers, and here I am, demining my land for myself and my loved ones.”

The FSD team clearing the village of Kamyanka near Izium has twelve members, almost all from eastern Ukraine—Kharkiv, Luhansk, and Donetsk. Most owned businesses or held leadership positions before the major war. All are mature, ironic, and know exactly what they are doing here.

Fifty-year-oldOleksii Kryvosheya has a patch on his uniform that reads, “Deminers Investigating. Last Season.” Once, he enjoyed searching for coins with a metal detector in his spare time. Now, working with a metal detector is no hobby, especially when he finds several butterfly mines a day.

“Our schedule is ten workdays, followed by four days off. So we spend more time together than at home. Our team is somewhere between a military unit and a family. And our team leader, Halyna, is like a mother to us.”

A Safe Place for Her Granddaughter

Halyna Burkina smiles beneath her visor. Energetic and speaking rapid, fluent Ukrainian better than others, she has survived two occupations and two dramatic evacuations—from Debaltseve in 2015 and Svitlodarsk in 2022.

A petite, fit 55-year-old woman, she leads a team of twelve men. The Diia app lists her occupation as “demining sapper.”

“In the field, it doesn’t matter if you’re a man or a woman. Everyone gets equally dirty, everyone gets equally tired, and everyone must follow the same standards,” Halyna says.

Her team isn’t weighed down by stereotypes that demining isn’t for ladies. ToOleksii, Halyna is first and foremost a leader.

“It’s Russia where women are housebound or treated as servants, our women descended from the Amazons. In my Territorial Defense unit, over 10% of the fighters were women, so female deminers don’t surprise me. Halyna is a leader: thorough but caring.”

Oleksiy Kryvosheya reports the day’s demining progress to Halyna, who asks about his scissors’ condition, which are used to cut grass before demining. As a leader, she wants her team to have the best tools.

Around a third of all deminers in Ukraine are women, according to the Ministry of Economy, and their numbers are expected to grow as Western countries actively recruit Ukrainian women for training.

“We check every tiny inch. It’s probably a motherly instinct—to do everything possible to prevent casualties.”

Halyna’s three-year-old granddaughter now lives in western Ukraine. The deminer hopes that, one day, the east will be safe for her too.

Fields Behind Their Backs

Virtual reality goggles, joystick controllers, radios, and clear visors. The people operating aerial drones and ground robots look like characters from a cyberpunk novel. But this modern team is searching among flowered fields for primitive remnants that, by all international conventions, should have long been relegated to history.

The HALO Trust, the largest international demining organization, works in Kharkiv Oblast, as do FSD teams. Grenades, anti-vehicle mines, tripwire booby traps, butterfly mines, shells, bullets, and shrapnel all lurk in the fields, flowers, and soil around a small, war-ravaged village in the Chuhuiv district. A total of 500,000 square meters of confirmed hazardous area.

Demining here is done in stages. After a complex non-technical survey, a yellow-and-black robot car mows vegetation and clears tripwires. It’s remotely operated. Only after the robot’s done does the team enter to clear the land by hand.

“If you look around, on every one of these fields you see someone has been blown up by a mine.”

Danyil Aliiev removes his visor and sets down his metal detector for a short break. Before the war, he was a surveyor in Kramatorsk, a city surrounded by fields of sunflowers and wheat. Now he leads a demining team, and all he can see today is one demining site after another. There are currently twenty-four demining sites around the village, but one field has already been returned to the people and is now safe.

“Behind me is a field the HALO Trust team has already cleared. Farmers have planted wheat there. It’s once again land that produces a harvest, feeding families—and that’s a good feeling.”

Danyil is 22, and among his team is 57-year-old Vitalii Yarovyi, who doubted he could qualify for such physically demanding and dangerous work.

“I already have two granddaughters, both eight years old. I wanted to be useful. My family and I collectively decided I should try. And, despite my age, I passed the training and am now working.”

Vitalii asks where he can see his photos in the deminer’s protective vest. He wants to send them to his son, who is fighting in the Armed Forces of Ukraine in the east. His break ends, and he takes his metal detector and resumes scanning the land.

Vitalii left Sievierodonetsk before 2024 with his family after Russian forces occupied it in early summer 2022. Before the invasion, he was an engineer. Now, he hopes to return to his city, when it’s liberated, as a deminer who will reclaim his own land as safe.

Translation — Iryna Chlapchii

§§§

[The translation of this publication was compiled with the support of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework “European Renaissance of Ukraine” project. Its content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union and the International Renaissance Foundation]