Tymur Ibrahimov was born in 1985 in Uzbekistan. Since 1991, his family has lived in Crimea. He attended a school for gifted children and later studied philology, specializing in English and Ukrainian languages.

Since 2007, Ibrahimov has worked as an entrepreneur, repairing and selling equipment, such as computers and phones. In 2008, he got married. He and his wife, Dilyara, have four children—two sons and two daughters.

In 2014, Ibrahimov became a citizen journalist, filming and editing videos that independent media outlets used to inform their audiences about events in Crimea. He recorded searches and trials of arrested Crimean Tatars. As a volunteer, he also supported the families of those unlawfully imprisoned.

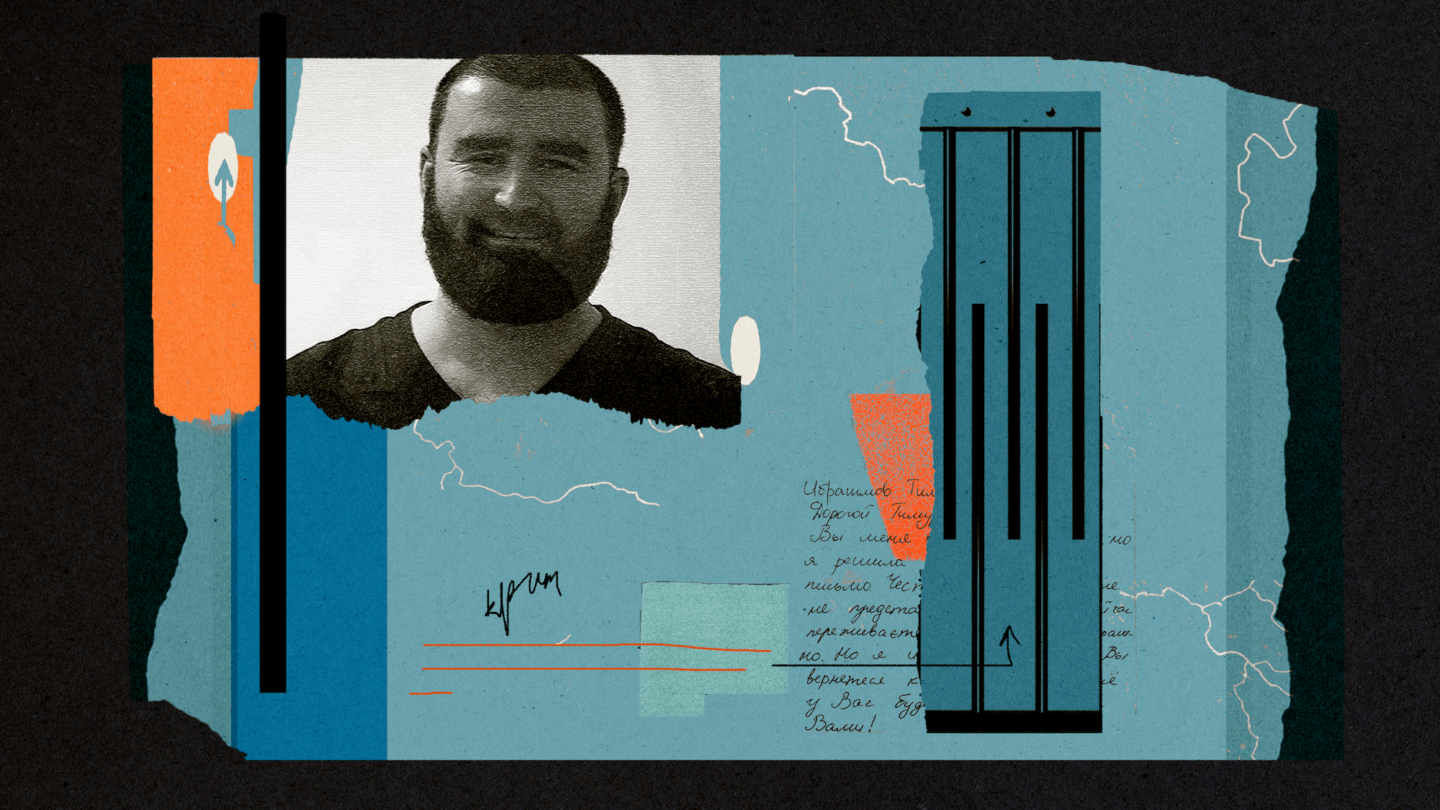

On October 11, 2017, FSB officers came to Ibrahimov’s home with a search warrant. He was charged under two articles of the Russian Criminal Code: Part 2 of Article 205.5 (“participating in the activities of a terrorist organization”) and Article 30, Part 1, in conjunction with Article 278 (“actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power”). Ibrahimov has been in custody since October 11, 2017. His “trials” were held in Rostov-on-Don. He was sentenced to seventeen years in prison and is serving his sentence in the Ryazan region.

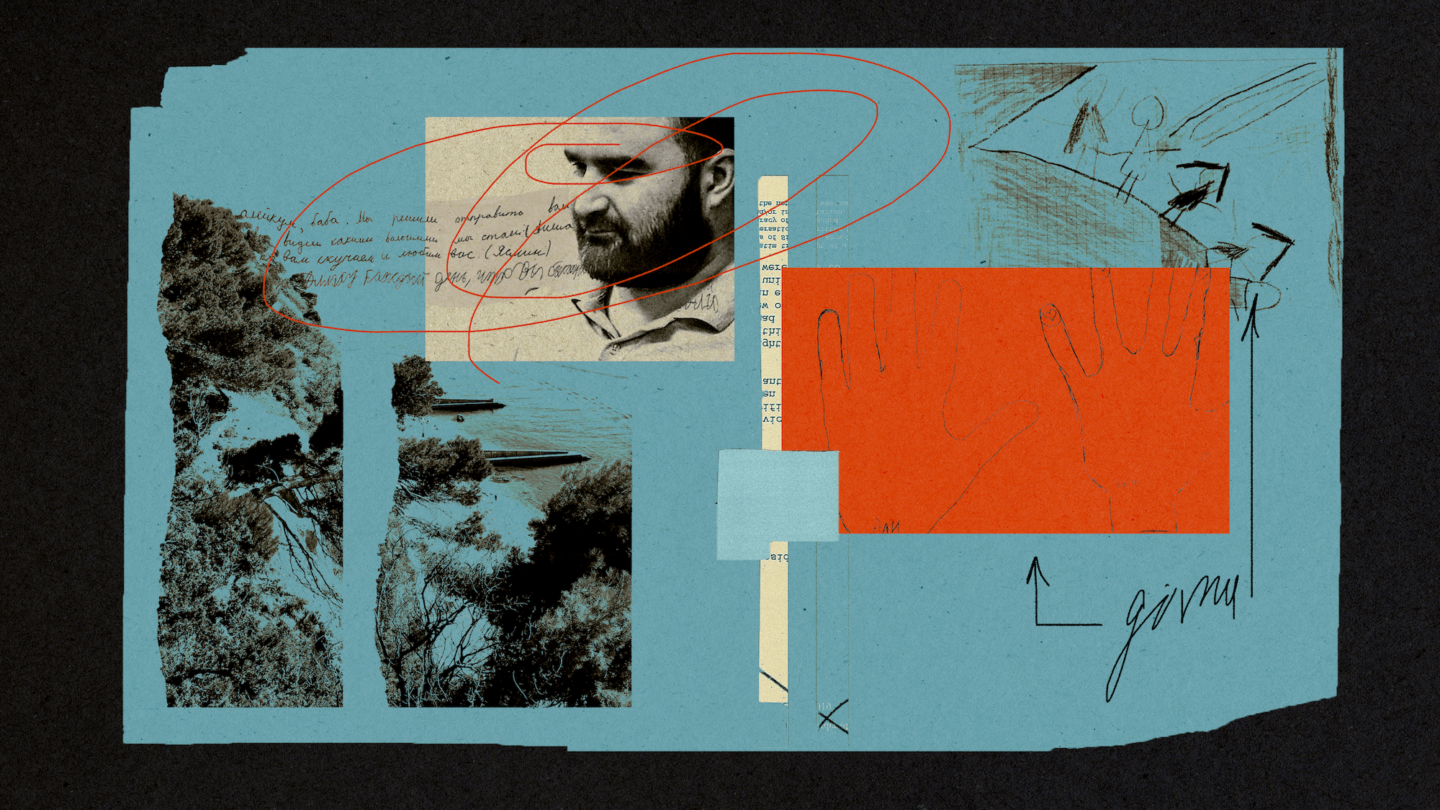

Ibrahimov’s youngest son was only ten days old when his father was arrested. They saw each other for the first time when the child was eighteen months old, in 2019, inside the FSB detention center. The family reunited again only in 2022—this time visiting Tymur in the penal colony.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

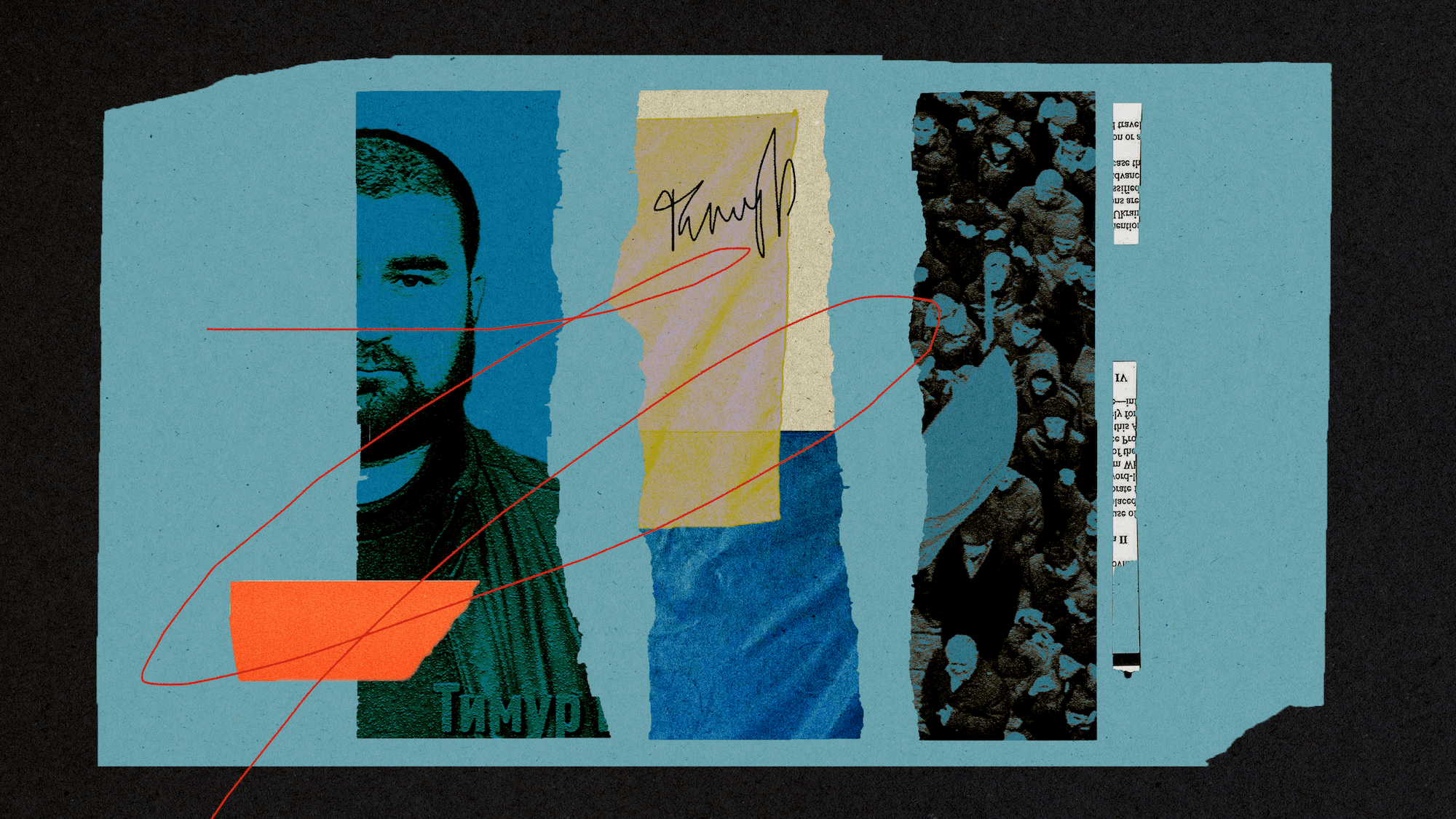

“Truth will triumph, not lies. Welcome us warmly, beloved Bakhchysarai!”—Tymur Ibrahimov ends his poem with these words. At the bottom of the grid-lined page, where seven stanzas are written in block letters, is Ibrahimov’s bold signature and the date 02.02.202… — the last digit is hard to make out. A few years earlier, in October 2017, Ibrahimov was arrested. Thus began yet another chapter of politically motivated persecution by Russian occupiers in Crimea.

A gifted child

Ibrahimov is a descendant of a family that, like thousands of other Crimean Tatars, was deported from Crimea by the Soviet regime in 1944. When his parents returned to their homeland, the boy was six years old. Four years later, his father was killed—one tragic evening, drunken strangers murdered him right on the street where he lived.

After his father’s death, Ibrahimov enrolled in a boarding school, the Tankivska Gymnasium for Gifted Children. He excelled academically, easily passing the entrance exams for the school. It was his mother who encouraged him to try. Studying in a good and prestigious school was her way of keeping him off the streets, away from dangerous influences and other risks.

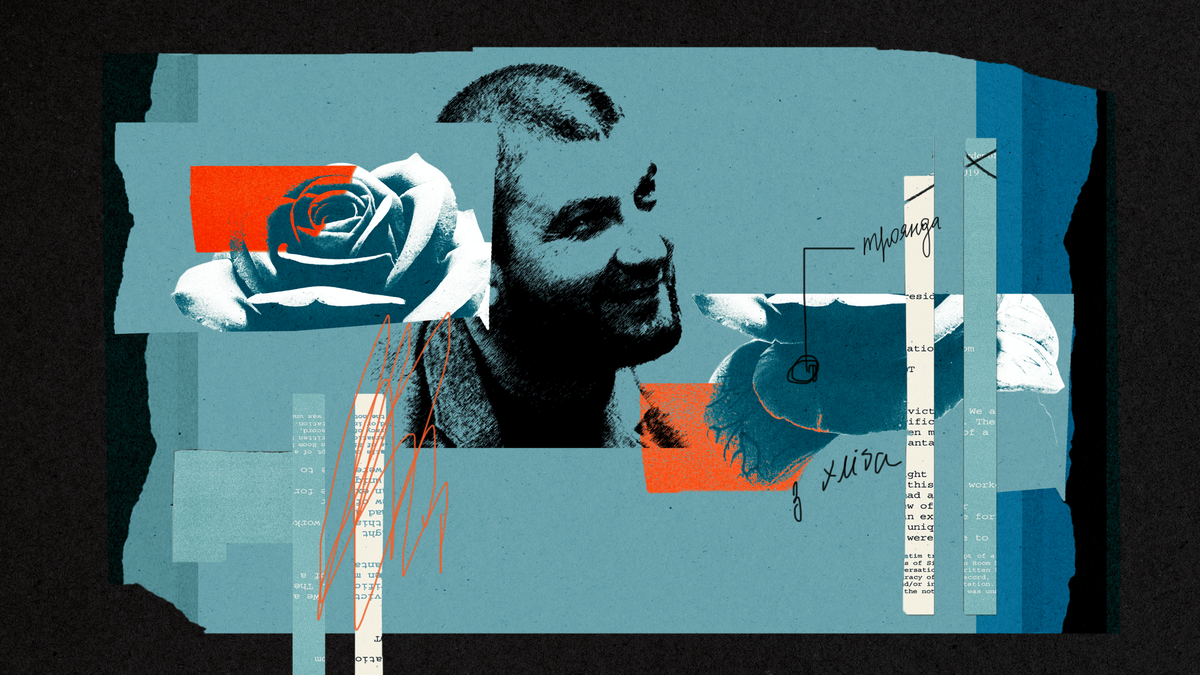

It was thanks to this school that Ibrahimov met his future wife. He would commute from his native village of Mostove to the village of Tankove, where the school was located—or, using their historical names, from Mordvynov Khutir to the village of Büyük Süyren. Dilyara’s father was a driver who transported students living in the boarding school. He called the students “his children” and often invited them over for Iftar—the communal meal to break the fast during Ramadan. This is how Dilyara and Tymur first met. Their acquaintance continued as they grew older, and they worked together at a café during the tourist season. At the end of the summer, Ibrahimov unexpectedly proposed to Dilyara. She accepted.

“He just did it.”

After the wedding, the couple lived in Mostove before moving to Bakhchysarai—to one of the “Crimean Tatar settlements,” as Mumine Saliyeva calls it. Today, she, like Dilyara, is the wife of a political prisoner. Mumine’s husband, Seyran Saliyev, was also unjustly imprisoned by the Russian occupiers.

Ibrahimov and Saliyev were neighbors and long-time friends, and their families were close. Mumine recalls that Ibrahimov had a reputation as a smart graduate of a prestigious school: “Everyone knew him as an intellectual, a very sociable guy with aristocratic manners.”

Mumine also speaks of Ibrahimov as a very diplomatic person: “He would shake hands with opponents even after really heated arguments. He had a talent for bringing people together—even those with different worldviews. Tymur was a diplomat who knew how to find common ground with anyone.”

Ibrahimov worked as an entrepreneur—repairing and selling equipment from his shop. But with the start of the Russian occupation of Crimea, he found a new calling—videography. Dilyara recalls, “This was his favorite thing to do. Whenever he had the chance, he’d start recording on his phone. His photos and videos always turned out great.” She says Ibrahimov tried to film everything that happened in Crimea after the occupation began: “At that time, he didn’t think about why he was doing it. He just did it.”

Mumine, a human rights activist herself, adds a few important details about Ibrahimov’s video documentation: “He was fluent in English and skilled in video editing. So he could easily handle the raw footage—process it, and quickly edit it. We would then share these materials with our colleagues—professional journalists.” Thanks to Ibrahimov’s footage, Ukrainian television channels were able to show what was happening in Crimea. Mumine emphasizes, “Tymur was one of the first to document the searches and arrests in Crimea. He is rightly considered a citizen journalist.”

Solidarity

Ibrahimov regularly visited the families of Crimean Tatars unlawfully detained by the Russian occupiers. Mumine says he recorded their testimonies, documenting what was happening, and offered help as a volunteer: “This included helping their families around the house. During his visits, he would pay attention to how people were living. We would later work on solving the problems he identified.” In her opinion, Ibrahimov’s own experience of losing his father and growing up as an orphan motivated him to help others, especially the children of those unlawfully imprisoned: “Because they, too, became orphans, even though their parents were still alive.”

Dilyara mentioned that during one of the meetings with the family of a political prisoner, which Ibrahimov was documenting on camera, the idea to create the organization Crimean Solidarity emerged. The goal was to provide systematic support for families in similar situations.

Did he realize that such activity was not safe under occupation? Dilyara recalls that they discussed the possible risks: “He understood it, but he always said he couldn’t just sit back and watch the injustice take place. I asked him to be more cautious. I worried, but I never discouraged him because I understood that these families truly needed help. I think Tymur was ready for the fact that they could come for him, too.”

“He will not stray from his path.”

Dilyara had spoken with her husband about the possibility of his arrest: “He documented many events, and his videos were often used as the basis for news reports. For example, when there was a raid at the neighboring house of the Saliyevs, Tymur immediately turned on the camera and rushed there to film everything. That’s when the first threats from the FSB were made—they explicitly told us that we were next. But Tymur said that he was already here and that he would not stray from his path.”

It’s impossible to be fully prepared for the first search or arrest. However, the Ibrahimov family were already familiar with what it entailed: A year before, Dilyara’s sister’s husband was detained. So Dilyara knew very well what happens to a family left alone without its father and husband: “I saw my sister and how hard it was for her with five children. At that moment, I had already accepted the situation that was to come. We couldn’t change anything.”

That day, Dilyara woke up early to feed the baby: “I had just returned from the maternity ward with our fourth child. It was about ten or eleven days after giving birth. While feeding the baby, I received a phone call. Early morning calls among our women are common, but they usually don’t bring good news.”

There was no good news this time either—Mumine called to inform her about new searches. Dilyara recalls waking up Ibrahimov, who immediately started posting about the searches on social media.

And suddenly—a new sound. Dilyara describes how Ibrahimov froze and began to listen: “We live on the fifth floor, and the sound of neighbors walking up the stairs is always clear. So that early morning, when everything was quiet because most people were still asleep, we could distinctly hear the approaching steps of fifteen people. At that moment, I knew: It was our turn.”

During the search, the investigator told Dilyara that Ibrahimov would not be coming back and even tried predicting his possible sentence—before the investigation and trial had even begun. He told her to pack his things.

Sneakers without laces, sportswear, T-shirts—everything preferably in black. Dilyara packed the bag, having memorized the list of items allowed in the detention center by then.

The trial

Dilyara notes that Ibrahimov’s case was one of the first, so the Russian occupation prosecutors still lacked experience: “Those early trials were lengthy, dragging on for two years.” Ibrahimov was not being tried alone—together, they were assembling the so-called Second Bakhchysarai Group, as the occupation forces labeled the Crimean Tatars arrested in Bakhchysarai and falsely accused under the so-called Hizb ut-Tahrir case. Six were arrested in October 2017, and two more in May 2018.

At a certain point, the court hearings in Rostov-on-Don were held every weekday from morning until evening. Ibrahimov’s mother was present at every session. Despite having to care for four children, Dilyara tried to attend at least once a week.

The Russian-controlled court sentenced Ibrahimov to seventeen years in prison—one of the harshest sentences handed down to the wrongfully prosecuted Crimean Tatar activists.

Mumine interprets such a lengthy sentence as a way to instill fear among the civilian population of Crimea. She calls it part of the “security services’ manual” and adds that this trend emerged after the adoption of the “Yarovaya package”—laws allegedly aimed at combating terrorism, which, in reality, only expanded the powers of Russian security forces.

Ibrahimov told Dilyara about his shock at the conditions for prisoners—he said he had only seen such things in movies before: “He remembered how they shackled each of them by the leg to a large chain—one for everyone. They shackled their hands in the same way. Then they had to walk in a line like ants—it was both funny and very difficult because they not only had to walk but also carry their bags, holding their hands in front of them,” Dilyara recounts.

Prison

Ibrahimov is being held in a colony in the Ryazan region. It was only a year ago that he saw his youngest son for the first time since his arrest. His son was only ten days old when the occupying forces came for his father. The next time Ibrahimov saw him was six years later.

For that first visit, which lasted three days, Dilyara took their eldest daughter and youngest son: “We didn’t know what to expect on the road, how everything would go, so I took two children with me, not all four.”

Such visits are allowed once every four months. For the next visit with their father, the older son and younger daughter went.

Later, Dilyara traveled with her mother-in-law. In the summer of 2024, she took all the children to visit their father. Next time, they will go as circumstances allow.

Ibrahimov tries to pass on important ideas to his children. Dilyara highlights three key principles: “First, he urges them to adhere to our religion—this is the first thing a person can do for both themselves and others. Second, he encourages the children to listen to me.

He says that he cannot provide them with proper fatherly guidance, so I, as their mother, am the most important person. Third, he reminds the children of the importance of a good education.”

Ibrahimov talks to his children not about good grades but about the importance of learning. He emphasizes the need to strive for knowledge, acquire it, and use it to benefit others. He calls it selfish to use knowledge only for one’s own benefit and insists that it should serve all of humanity.

The family tries to have weekly video calls, and daily voice calls with relatives are also allowed, so they manage to maintain contact.

However, Ibrahimov is experiencing health issues in prison. He needs an eye implant replacement, as Dilyara reported after a visit in the fall of 2023. He received the previous implant fifteen years ago, and now it needs to be replaced. Mumine adds that during his imprisonment, Ibrahimov has lost a lot of weight—seventeen kilograms.

Even in prison, Ibrahimov seeks ways to find strength and support himself. The first is reading the Qur’an. He has the same one as Dilyara at their home in Bakhchysarai, and reading it is the couple’s way to stay connected. The second is work, as there is a sewing workshop in the colony where even a person with visual impairments can find something to do. The third is letters. Ibrahimov receives many letters not only from Crimea and Ukraine but also from different countries around the world, which is a source of great support for him.

The materials (facts, interviews) for this article were provided by Olha Dukhnich.

This text was written in July–August 2024.

Translated by Yevheniia Dubrova.

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано світлини із родинного архіву, а також Кримської солідарності.