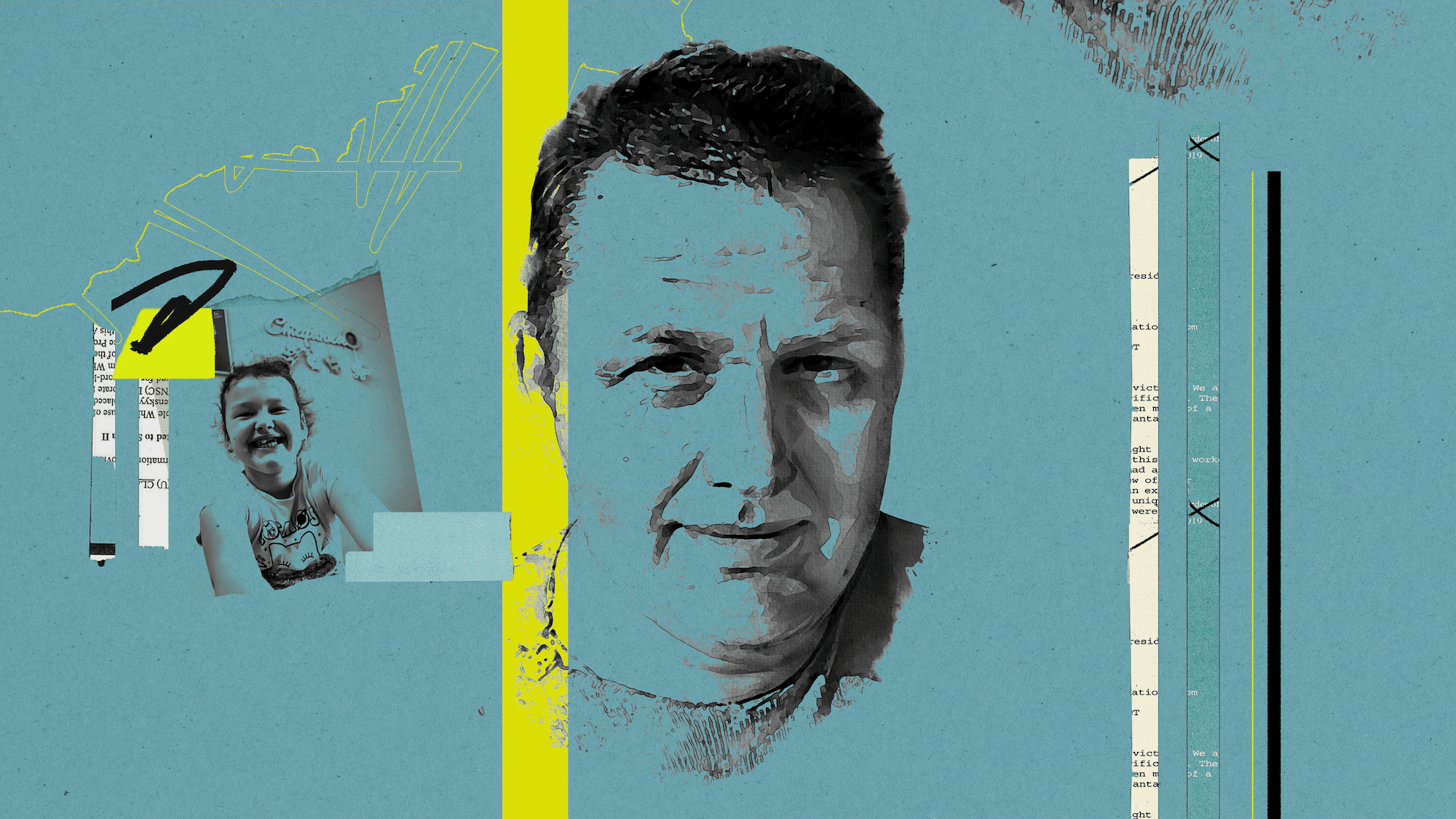

Vladyslav Yesypenko is a freelance journalist working for Krym.Realii (Crimea.Realities), a project of the Ukrainian Service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. He was born on March 13, 1969, in Kryvyi Rih.

Yesypenko was detained on March 10, 2021, at Anharskyi Pass, part of the Simferopol–Alushta highway in Crimea. The day before, he had been filming a commemoration of Taras Shevchenko during an ad-hoc campaign. He was charged under Article 223.1 of the Criminal Code of Russia (“The illegal manufacture, remaking or repair of firearms and illegal manufacture of munitions, explosives or explosive devices”) and Article 222 (“Illegal acquisition, transfer, sale, storage, transportation, or bearing of firearms, its basic parts, ammunition, explosives, and explosive devices). Yesypenko was sentenced to six years in a general penal colony. Later, the court of appeal reduced his sentence to five years. He is currently serving his sentence at Kerch Colony No. 2.

Ukrainian and international human rights organizations insist that his case is politically motivated.

In 2021, Yesypenko was awarded the Levko Lukianenko State Scholarship, and in 2022, the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

On March 10, 2021, between 3 and 4 p.m., Kateryna Yesypenko was at home in Kryvyi Rih, trying to reach her husband who was in Crimea. Vladyslav Yesypenko, a freelance journalist working for Krym.Realii (Crimea.Realities), a project of the Ukrainian Service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, had traveled to the occupied peninsula on a regular business trip. He had not been in touch with Kateryna that day, but she knew he was supposed to be interviewing someone in Simferopol.

“I knew he was supposed to go there with the person who was hosting him,” Kateryna says. “I had her number. I called her, and her phone was on, but she never picked up. I had a gut feeling that something happened. But I was thinking of a car crash, or maybe he was taken to hospital. I couldn’t even imagine this could be the FSB. I learned that Vladyslav was detained only after the house search when the person who was present during the detention called me from a different number and told me everything.” [Her husband was detained prior to the house search.]

Russia’s FSB officers stopped Yesypenko’s car at Anharskyi Pass. There were two people in the car: Yesypenko and Yelyzaveta Pavlenko, a resident of Alushta. Later, Pavlenko would appear in court as a defense witness in Vladyslav’s case.

In the indictment, Russian prosecutor Sergei Zaytsev stated the reason for the journalist’s arrest as follows: “He agreed to pick up an RGD-5 hand grenade from a cache near the village of Pravda, Pervomaisk district. On February 23, 2021, he took out a grenade body with explosives and a fuse from a UZRGM-2 hand grenade in the cache, assembled it all as one device, and brought it with him in the car.” Initially, the documents from the occupation prosecutor’s office stated the reason for Yesypenko’s actions as “self-defense against aggressive Tatars.” This reason was later changed to “ensuring personal safety” — an equally farcical allegation.

“I still don’t understand why FSB officers chose a grenade for ‘self-defense against Tatars’ rather than a gun,” Yesypenko wrote ironically in one of his letters. “Does this mean that if I came across ‘aggressive Crimean Tatars,’ I was expected to blow them up along with myself contrary to the instinct of self-preservation?”

Joking in hell

In the letters sent to the editorial office of Krym.Realii and later published there, Yesypenko detailed how he was coerced into testifying against himself. He explained that he had refused to sign the protocols after the house search, and then the Russian security officers threatened to take him to a different place where they “made much bigger shots talk.” They brought him to Bakhchysarai and took him to a basement, where they stripped him and hooked electric wires to his body. “The boys worked in coordination and without emotion,” Yesypenko wrote. “They asked me questions in between torture sessions.”

He recalls that after hours of screaming and pain, his mouth was constantly dry, and his tongue started to bleed.

The officers gave him a choice: either they continued with electric shocks, or he did push-ups.

Yesypenko chose to do push-ups, but the torture continued. Afterward, they had him sit on a chair and taped him to it. “I joked like crazy. It was joking in hell,” he wrote. “Lying in that basement, I said to the FSB men that I wouldn’t even need to go to the gym with such heavy workouts. Hearing that, they only kicked me harder, saying I was mocking them.”

They tortured him for two days. The torture was so severe that he was forced to testify against himself and read a script written by the FSB officers on camera. “I knew that if I didn’t testify against myself,” Yesypenko wrote, “the FSB officers would keep trying to ‘make me talk,’ and I would become disabled by the time of the trial, if not dead.”

Yesypenko denied the testimony he had given against himself during the very first trial in the Simferopol court. He explained that he had signed the testimony under physical and psychological duress. An independent lawyer was allowed to meet with Yesypenko twenty-seven days later. Denis Korovin, one of the FSB officers, visited Yesypenko at the pre-trial detention center and complained that he “said too much in court,” insisting that he admit his guilt. On a different occasion, he brought Yesypenko new sweats and tried to persuade him to decline the services of independent lawyers. When Yesypenko refused, Korovin offered another argument: “But we bought new sweats for you.” This is a fragment of Korovin’s testimony as a witness during the trial. He denied ever visiting Yesypenko at the pre-trial detention center. None of the Russian FSB officers were punished for torturing Yesypenko.

Olha Skrypnyk, chair of the board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, explains that torture is an integral practice of the FSB. “Back before the full-scale invasion, the Crimean Human Rights Group analyzed all the ongoing proceedings in Crimea under the ‘abuse of power’ article,’” she says. “This is the only article applicable to the FSB for torturing people. But not a single person has been sentenced under this article since Crimea was occupied.”

I [Oleksandra Yefymenko] was not allowed to attend the Yesypenko trial. During the court sessions, I was in occupied Crimea as a freelance journalist, reporting on the cases of Ukrainian political prisoners. Russian judge Diliaver Berberov did not allow me into the courtroom. I spent the whole time in a café across the street from the court building where the Russian system was framing my colleague. After the sessions, as they led Yesypenko out of the building to take him back to the pre-trial detention center, I would come up to the door and stand in a spot where he could see me. I waved my hand, and he would sometimes wave back to the people who gathered outside in solidarity. I had never met Yesypenko before his imprisonment. I first saw him in the glass dock in court.

Journalism as a response to the occupation

The occupation of Crimea unfolded before Yesypenko’s eyes. He filmed extensively on his phone: blocked Ukrainian military bases in Crimea, strikes, land grabs by the Russian army, and polling stations during the ‘referendum.’ He had a lot of footage, and a few years later, he decided to revisit the subject of Crimea. Yesypenko offered his archival footage to various Ukrainian media and expressed his willingness to continue working in Crimea.

“But it turned out that the Ukrainian media weren’t very interested in this topic,” Kateryna, Yesypenko’s wife, recalls. “Vladyslav was stunned by this, to put it mildly. He just couldn’t understand how Crimea could be seized in front of the whole world, but Ukrainian media didn’t even want to cover it. Later, Vladyslav contacted Krym.Realii, and they started to collaborate.”

Up to that point, Yesypenko had nothing to do with the media. He was involved in the real estate business.

“I didn’t try to talk him out of working in Crimea,” Kateryna says. “I never told him not to do this or that or set any conditions. When the issue of potential repercussions for his activity came up, he assured me that everything would be alright.”

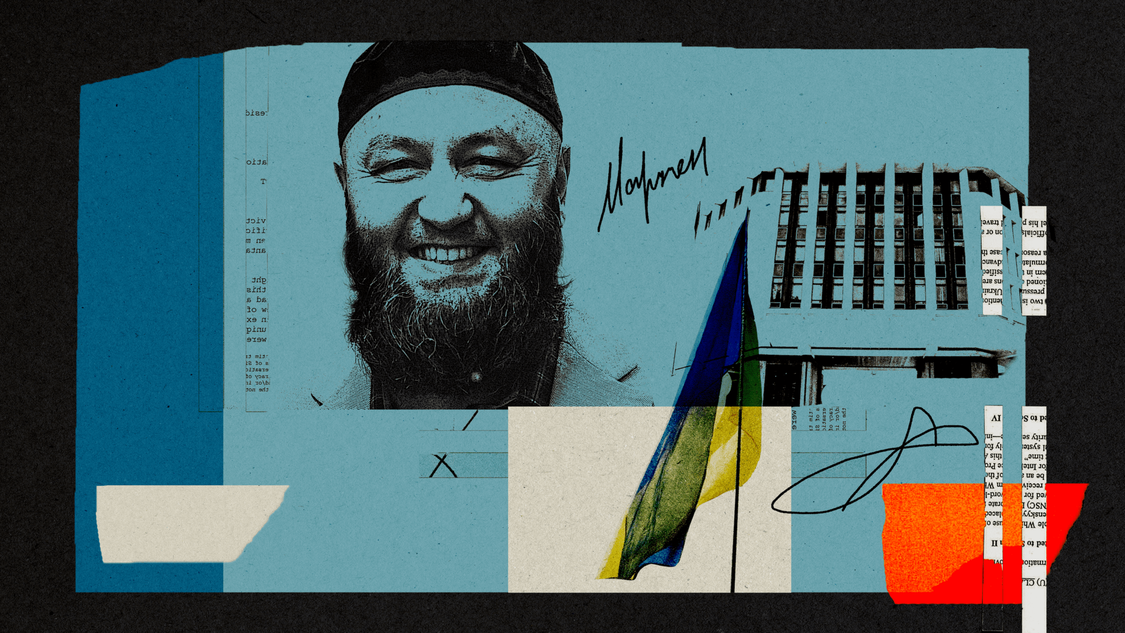

Yesypenko covered social and environmental issues and always worked under a pseudonym. His last published work was a survey of Crimean residents on how their lives had changed over the seven years of occupation. He asked people about the blocking of social media, covered illegal sand mining on the Bakal Spit, and described the current state of the Tavryda soccer training base. All of his materials can still be accessed on the Krym.Realii website.

Skrypnyk stresses that in the context of journalist persecution in Crimea, Yesypenko’s case is one of the few in which the occupation authorities explicitly admitted to persecuting journalists for their activities. “When they first started framing Vladyslav, they tried to use the video footage he’d made about everyday life in Crimea as evidence,” she says. “So, his journalistic activities were clearly labeled as a crime.”

This is how Yesypenko opened his final statement during the trial in Crimea: “I consider this case political. Why? Because I’m a journalist working for the Ukrainian media, and most probably, the FSB officers wanted to show how unacceptable freedom of speech is.”

Yesypenko managed to continue working as a journalist even behind bars. He recorded a conversation with his civil defense lawyer, Metropolitan Klyment of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in Crimea and Simferopol. While in prison, he also conducted an interview with another prisoner, Kostiantyn Shyrinh, a Ukrainian citizen detained in April 2020 on espionage charges and sentenced to twelve years in a high-security penal colony. Shyrinh had heart problems and needed medical care but never received it. Shortly after the interview, he died at Colony No. 5 in Novotroitske, Orenburg region, Russia. The conversation, which was recorded in writing by Yesypenko and published by Krym.Realii, became Shyrinh’s first and last interview.

To find Remarque’s novel in the penal colony’s library

Yesypenko serves his sentence at Kerch Colony No. 2. There, unlike at the pre-trial detention center, he can call his family on the phone. However, he cannot send letters because this colony is not part of the Russian Zonatelecom system, and physical letters won’t be delivered to Crimea.

“Any institution where people are detained is a place of constant psychological pressure, and you have to be strong not to lose yourself there. Vladyslav found it hard to stay in a cramped solitary cell at the pre-trial detention center. When he was transferred to the penal colony, he and I even joked that it’s now better for him,” Kateryna says with a bitter smile.

Yesypenko stays in a colony barrack where thirty people are held at a time. There’s a makeshift athletic field and a library. Among the books about the history of Russia and Tsarist Russia, and collections of Lenin’s quotes, he found a novel by Remarque. Yesypenko studies English with the help of a fellow inmate who speaks the language well. He works with the textbook on his own, practicing speaking with the inmate. While in prison, Yesypenko also wrote a poem, set it to music, and created a script for the video clip for the new song. He sent all of this to his wife.

Yesypenko is also working on a book, and he sent some of its fragments to his wife as well.

“It’s not a documentary,” Kateryna says. “It’s a book about his life in the colony. It features fictional protagonists whose lives go on behind bars just like his own.”

When it comes to his own imprisonment, this is what Yesypenko wrote in his letter to his wife in Kryvyi Rih: “Sometimes it’s hard. Very hard.

The greatest humiliation is being reduced to a voiceless, rightless animal.

The worst kind of hell is sitting inside these four walls day after day, month after month—six months now—and only leaving the cell on command to snatch a breath of fresh air, only to return, helpless to change anything.”

“I won’t live under Russia”

Kateryna met Vladyslav thirteen years ago at a gym. He proposed to her on a mellow evening in early fall in Yalta. In 2013, they settled down in Sevastopol but didn’t get to live there for long since soon after, Russia occupied Crimea. Their daughter, Stefaniia, was born under occupation. “I won’t live under Putin,” Yesypenko flatly declared, and the family, with their baby daughter, moved to Kryvyi Rih in Ukraine. Stefaniia was six when her father was imprisoned. When I first visited their family, she kissed the TV screen upon seeing her father on the news. Stefaniia is nine now.

“She’s such a princess now,” Kateryna says. “Stefaniia talks to her father on the phone, and I get the impression that she comes back to life only when he’s around. They discuss all sorts of things: her days, her friends.” She adds that during a consultation, a child therapist mentioned that Stefaniia seemed to be eager to stay at the age she was when her father was imprisoned. In her every letter to St. Nicholas, the girl asks the saint to bring her father home as soon as possible.

“She knows everything; she understands everything,” Kateryna says. “She knows where her father is and why he’s held there. Our daughter is fine talking about it with others.”

On Stefaniia’s birthday, her father sent her a note from the prison. He wished her a happy birthday and asked her not to give up on music and dance. “To hold your little hands in mine. This would be my greatest happiness. I’m sure it will happen soon!” Yesypenko wrote to his daughter.

Kateryna became involved in human rights advocacy. She says that her work in this field is a direct consequence of her husband’s imprisonment.

“My involvement in my husband’s case influenced my choice,” she explains, talking about her current activities. “Most human rights advocates are now focused on documenting the war crimes of the Russian Federation in Ukraine. I feel I’m making my humble contribution to holding Russia accountable. Some people raise money to buy drones. Some actively volunteer. Others evacuate the wounded. And my goal is that after our victory, the Russian Federation is brought to justice.”

Skrypnyk, chair of the board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, clarifies the situation regarding the swaps of the Kremlin’s political prisoners, who are now considered civilian prisoners since the full-scale invasion began: “The process of a prisoner swap is not a legal procedure. It’s not a situation when we can definitively say that this or that person is eligible for it. In this case, these people shouldn’t be in prison in the first place.”

Since 2014, when the war began, there have been at least three cases of Crimeans being released from prison. They were Hennadiy Afanasiev, Ilmi Umerov, and Akhtem Chyihoz. As a result of another prisoner swap in 2019, Oleh Sentsov, Volodymyr Balukh, and Oleksandr Kolchenko returned to Ukraine. But since the full-scale invasion began in 2022, the process has been on hold. Russia deliberately stopped swapping Crimean Tatar political prisoners as it does not recognize Crimea as part of Ukraine and, accordingly, does not acknowledge that the war is ongoing there, too. “Vladyslav is on the swap list indeed, but for now, we don’t see any mechanism that could be used to release civilians,” Skrypnyk remarks. She adds that one potential mechanism could be a large coalition of countries acting on a political level to advocate for the return of Ukrainians to their homes.

This text was written in December 2023–January 2024

Translated by Hanna Leliv