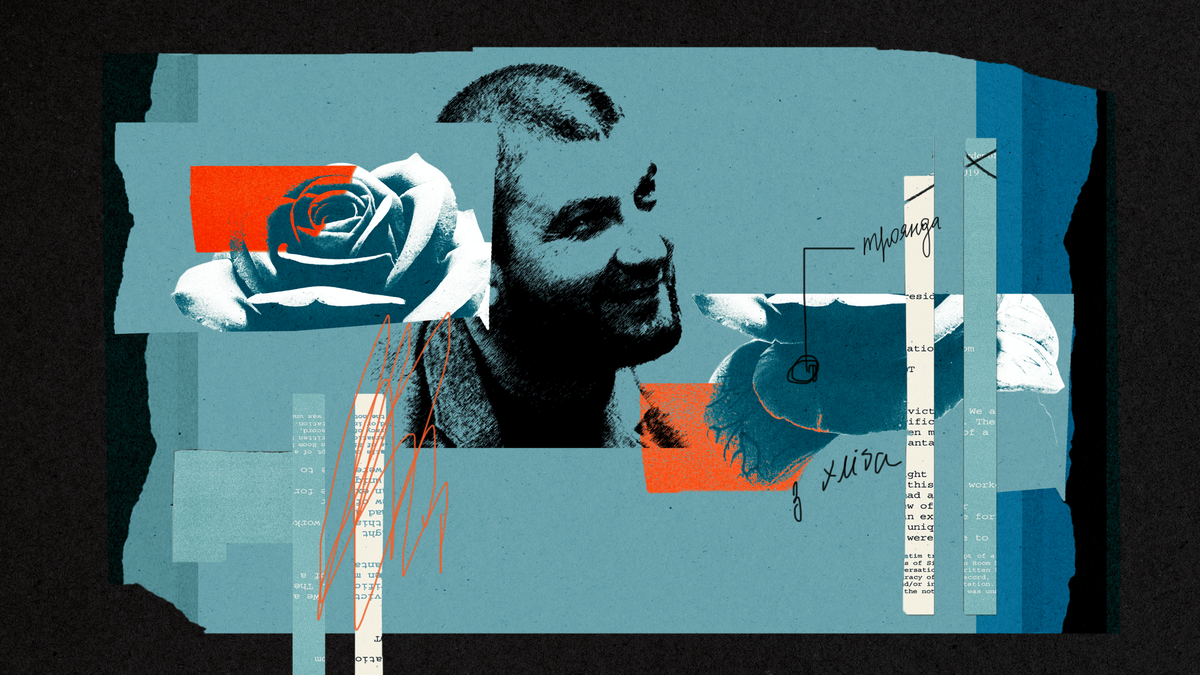

Ernes Ametov is a citizen journalist.

Ametov was born on May 30, 1985, in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. In 1992, his family returned to Crimea, settling in the city of Bakhchysarai. He graduated from Taurida National University with a degree in law. Ernes is married to Eleonora Ametova, and they have two sons.

On October 11, 2017, armed FSB officers stormed the Ametov household and conducted a search. Ametov was arrested, but three years later, the court acquitted him. However, two years after his acquittal, he was charged under Part 2 of Article 205.5 of the Russian Criminal Code for alleged “participation in the activities of a terrorist organization” and Part 1 of Article 30 and Article 278 for alleged “actions aimed at the forcible seizure of power,” and sentenced to eleven years in a penal colony plus one year of restriction of freedom.

Ametov is the grandnephew of pilot Amet-khan Sultan, a hero of the Crimean Tatar people.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

“Calm down, it’s the FSB.”

“Fire! Open the door!” somebody shouted. A loud knock and ruckus followed as people in uniforms burst into the Ametov family’s apartment during their morning prayer. Eleonora noticed her hands trembling from fear while she prayed, and when she saw a dozen Russian officers pointing guns at her and her husband, memories of her grandfather’s stories about the 1944 deportation flooded back. “They’re here to kill us,” she thought. “Calm down, it’s the FSB,” said Ametov, noticing Eleonora’s panic.

The raid on the Ametov home took place on October 11, 2017. That day, Ernes Ametov was arrested. He became one of the eight defendants in the second Bakhchysarai group of the Hizb ut-Tahrir case. The search lasted nearly five hours. Eleonora recalls feeling like the officers were deliberately dragging out the process, going through each document and confiscating some books—though they later returned them because they were not on Russia’s list of banned literature. Curiously, they did not search the kitchen.

Ametov was taken from their home while Eleonora stepped away to change clothes. “We jumped into the car and followed him. I remember being so worried they’d kidnap him, that he’d ‘disappear.’ And the day after the search, there was a trial,” Eleonora recalls.

The Ametovs have two sons, Aladin and Imran. At the time of the search, the eldest was eight, and the youngest was five. “Aladin woke up early before they knocked on our door and hid in the couch. Ernes asked him what he was doing, and our son said he was scared. It was like he sensed something.” When the officers began the search, they advised the Ametov children, “Don’t be afraid, just turn on some cartoons.” While the search was underway, Eleonora went into the kitchen to make porridge for her children. After the arrest, Imran kept asking his mother, “Why did they choose our door?”

Eleonora and Ernes met through a mutual acquaintance: Eleonora’s childhood friend and Ernes’s classmate. A month after their first meeting, Ametov proposed at the Khan’s Palace. “It felt like a scene from a movie.

He tied a string to my finger and slid a ring down it. He said beautiful words, that his life was in faith, in serving God, and he was inviting me into his life to make me happy.

Our first Kurban-Bayram together. I wasn’t practicing Islam then, just following traditions. In the morning, I woke up to a huge bouquet of roses. My husband said, ‘We don’t celebrate typical holidays like International Women’s Day or Valentine’s Day, but you’ll always get flowers without needing a reason.’ That’s how our family life began: pure, beautiful, and right,” Eleonora says.

“He wasn’t eating bread so he could make me a gift.”

Eleonora’s birthday was three months after Ametov’s arrest. At that time, he was in a Simferopol pre-trial detention center. “On the morning of my birthday, someone rang the doorbell. My children and I were scared at first, thinking it was another search. I opened the door and saw flowers and a card. The delivery person passed along some warm wishes from Ernes, saying my husband loved me very much. I was shocked.” Eleonora says that every birthday since her husband’s imprisonment, he’s managed to send her flowers. One time, she even received a rose made from bread that Ametov crafted in prison. Later, he told her that he had been saving his bread from prison rations to make her a gift.

Eleonora shares that her husband has always had a knack for making things with his hands: “Right after we got married, he installed internet cables. Later, he made custom built-in wardrobes and became passionate about working with cezves. He made brass cezves for coffee by hand. His work caught the attention of others, and he was invited to train in this craft in Turkey, but Ernes declined because he didn’t want to leave our family. He took a photography course, and we started filming weddings together and making wedding decorations. He inspired me to start a YouTube channel and film videos.” Eleonora adds that Ametov is a trained lawyer, though he never worked in his profession.

Ametov was shocked by the arrest of Rustem Abiltarov, a defendant in the first Bakhchysarai group of the Hizb ut-Tahrir case. Abiltarov was a good friend of his. Eleonora recalls the moment she and her husband learned the news of Abiltarov’s arrest—how they stood in silence, unable to speak. “I said, ‘They’re facing decades. The children won’t see their father for decades.’” Abiltarov was sentenced to eight years and nine months in prison. Since then, Ametov tried not to miss a single search or court hearing held on the peninsula.

Ametov began covering the repression as a citizen journalist. His colleagues say he started reporting on the stories of the detained after meeting their families. Ametov recorded interviews with the parents and wives of the arrested. He edited the videos himself and turned them into reports. Some of these interviews were published by the Crimean Solidarity organization.

After Ametov’s arrest, Russian security services pressured him to testify against the other defendants in the case. When he flatly refused, they told him, “Then you’ll sit in prison with them.”

This attempt by Russian authorities to coerce the defendant into testifying against others is not the first in the history of political persecution in Crimea. Raim Ayvazov, a defendant in the second Simferopol group of the Hizb ut-Tahrir case, was also pressured to cooperate. “They took me out to a field, staged an execution, threatened to kill me, and warned that no one would ever find me if I didn’t testify against the other participants in the case,” Ayvazov recounted at his first court hearing in the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don.

Enver Krosh recalled that FSB officers tried to recruit him in a police station: “They told me, ‘You have until noon. If you don’t agree to work with us, we’ll hand you over to the cops, and they’ll frame you in a drug case.’ I said I’d rather go to prison than become an informant.” They planted a bag of what they claimed were drugs in Krosh’s jacket. Later, they beat him and tortured him with electric shocks. That was in the winter of 2015, and in 2022, Krosh became one of the defendants in the Dzhankoi group of the Hizb ut-Tahrir case. His lawyer, Emil Kurbedinov, stated that the security officers beat Krosh in their car following his arrest.

Ametov was sentenced to eleven years in a strict-regime penal colony, accused under the familiar charge against Crimean Tatar Muslims: “participation in the activities of a terrorist organization.”

But before this, he became the only person in the entire history of Crimea’s occupation to be acquitted.

“Not guilty and not leaving Crimea.”

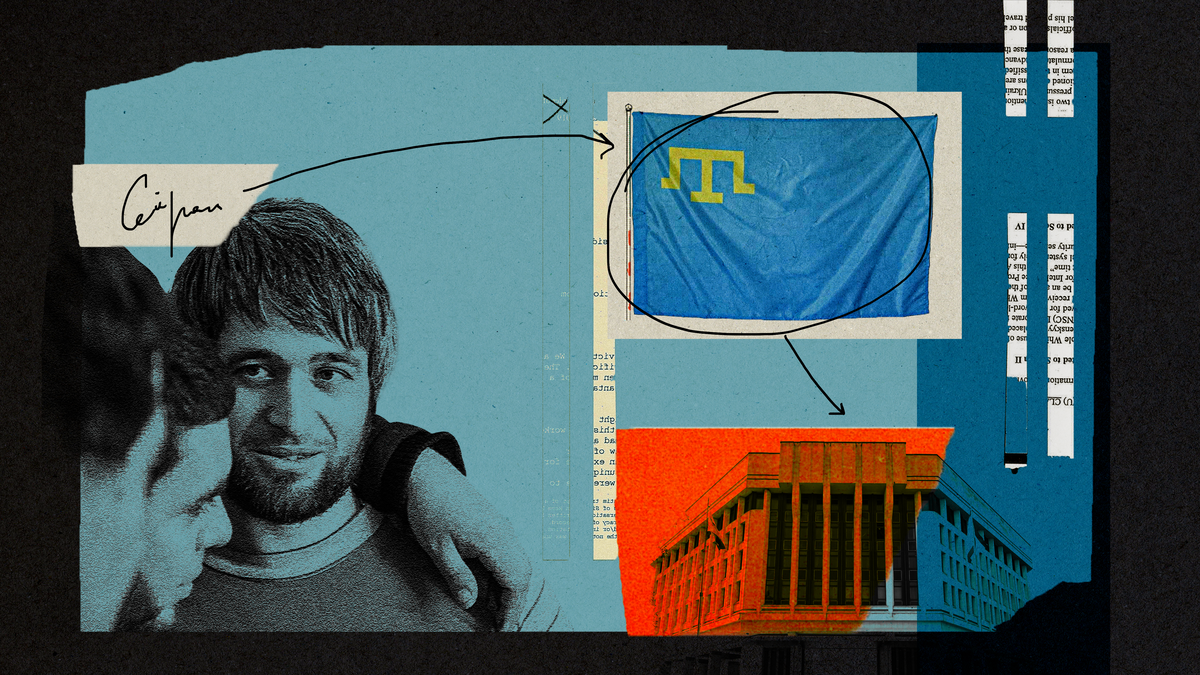

The second Bakhchysarai group of the Hizb ut-Tahrir case consists of eight defendants. According to the investigation, radio engineer Memet Belyalov “organized the activities of a terrorist organization,” while the founder of the Salachyk cultural-ethnographic center Suleyman Asanov, human rights defender Server Mustafayev, organizer of children’s and religious events Seyran Saliyev, entrepreneur Server Zekiryayev, religious community leader Edem Smailov, and citizen journalists Tymur Ibrahimov and Ernes Ametov are charged with “participation in the activities of a terrorist organization.” They allegedly held their “meetings” at the Khan Chair Mosque in Bakhchysarai.

On September 16, 2020, the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don announced the verdict. Lawyer Lilia Gemedzhi, who defended Server Mustafayev, recalls: “The session began with the announcement of the ruling. Often, judges read documents unclearly and indistinctly. It was hard to hear. We understood that the ruling was being announced, but for a long time, we couldn’t grasp the content of the document. We even began whispering among ourselves, and it took a while to realize that the ruling acquitted Ernes. To be precise in legal terms, the court determined that Ametov was a member of Hizb ut-Tahrir but had ceased his activities and voluntarily left the organization by the time of his arrest. During the trials, Ernes insisted this was a lie; he had never been a part of this organization, and other defendants in the case confirmed his testimony. However, the court based its decision on the testimony of a secret witness. After this ruling, the sentences for the other defendants were announced. We found it hard to believe that Ernes was acquitted.”

Ametov’s acquittal came as a surprise even to FSB officers. In his court speech, Ametov dismissed the prosecution’s claims, explaining point by point why the charges against him were fabricated: “I have already spoken about my presence at the gathering in the mosque, but I’ll say it again—this event and the conversations cannot be viewed by the investigators as a connection to Hizb ut-Tahrir. No one ever spoke to me about HT during these events, nor did I take any oaths or obligations. It was a free visit to the mosque, which I enjoyed because of its informal nature and the topics discussed at these gatherings. These included the Qur’an, Sunnah, Hadiths, and Islam’s view on modern realities.”

Gemedzhi notes that later, she and other lawyers reflected on the case and concluded that Ametov’s acquittal was a personal decision by the presiding judge, Rizvan Zubairov. “Whether it was his independent decision as the head of this criminal case or a coordinated one, we don’t know. We can only speculate. If a judge makes a decision that is later overturned, it negatively affects their career statistics. Waiting for the appeal to overturn this decision was unacceptable. We immediately advised Ernes to leave because, legally, he was free. No restrictions could be applied to him. But I remember his position: He said he was not guilty and would not leave Crimea,” Gemedzhi recalls.

“They uproot us like weeds.”

Eleonora recalls her memories of Ametov’s first moments of freedom. She saw him outside the court building—for the first time in three years outside the courtroom “fish tank.” He came out in a jacket and a kalpak [traditional Crimean Tatar male headwear]. “He stood there looking so handsome, like an actor,” Eleonora says. At that session, Eleonora wore a fes, and Russian prosecutor Yevgeniy Kolpikov complimented her: “He said I had a very beautiful headdress,” Eleonora recalls. Later, Kolpikov filed an appeal to review the court’s decision to release Ametov. “When we traveled back from Rostov-on-Don with Ernes in 2020 after his acquittal, he brought his backpack with personal belongings from the detention center. He never unpacked it. That backpack lay in the room next to the sofa for a year and a half. Ernes told me right away, ‘They won’t let me go, I don’t want to get used to being home,’” Eleonora recounts.

In April 2022, Ametov’s case was returned to court. He voluntarily appeared at the preliminary hearing of the retrial. Judge Aleksey Magomadov ordered Ametov to be held in custody for two months. Thus, Ametov ended up back in the Simferopol detention center. On November 30, 2023, the Military Appeals Court in Vlasikha (Moscow region) handed down a sentence: eleven years of imprisonment for Ametov. He is currently serving his sentence in a colony in the Vologda region, in the village of Sheksna, over 2,000 kilometers from Crimea.

During his final speech in court, Ametov said: “The FSB, through these persecutions, is creating a sterile ideological environment to impose its way of thinking, which is incompatible with the mindset of Muslims. They are identifying and removing undesirable elements from society, like me, like my fellow Crimean Tatar prisoners. They uproot us like weeds. This way, the FSB corrects the course of development for this society. They want to create a homogenous environment, a kind of sterile population that has no independent view of life or events and is only supposed to live as the current authorities dictate.”

In the summer of 2024, Eleonora and their sons went on a long visit to see Ametov. “For those three days of being next to him, emotionally I felt like I went to the Maldives. The colony is a very unpleasant and dangerous place, but being next to my husband and children, when the four of us stood together and hugged for the first time, I felt absolute happiness.

He’s lost so much weight—when I saw him, I was very upset. There’s no halal food in the colony, so he eats minimally, just enough to have strength.

He works in the colony. He has become quite skilled at sewing. He says it helps him distract himself.”

Ametov does not share many details about life in the colony with Eleonora: “One word—prison,” is his short answer to all questions.

This text was written in August 2024

Translated by Yevheniia Dubrova

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано ілюстрацію Марії Глушко, світлини й листи з родинного архіву, а також Кримської солідарності.