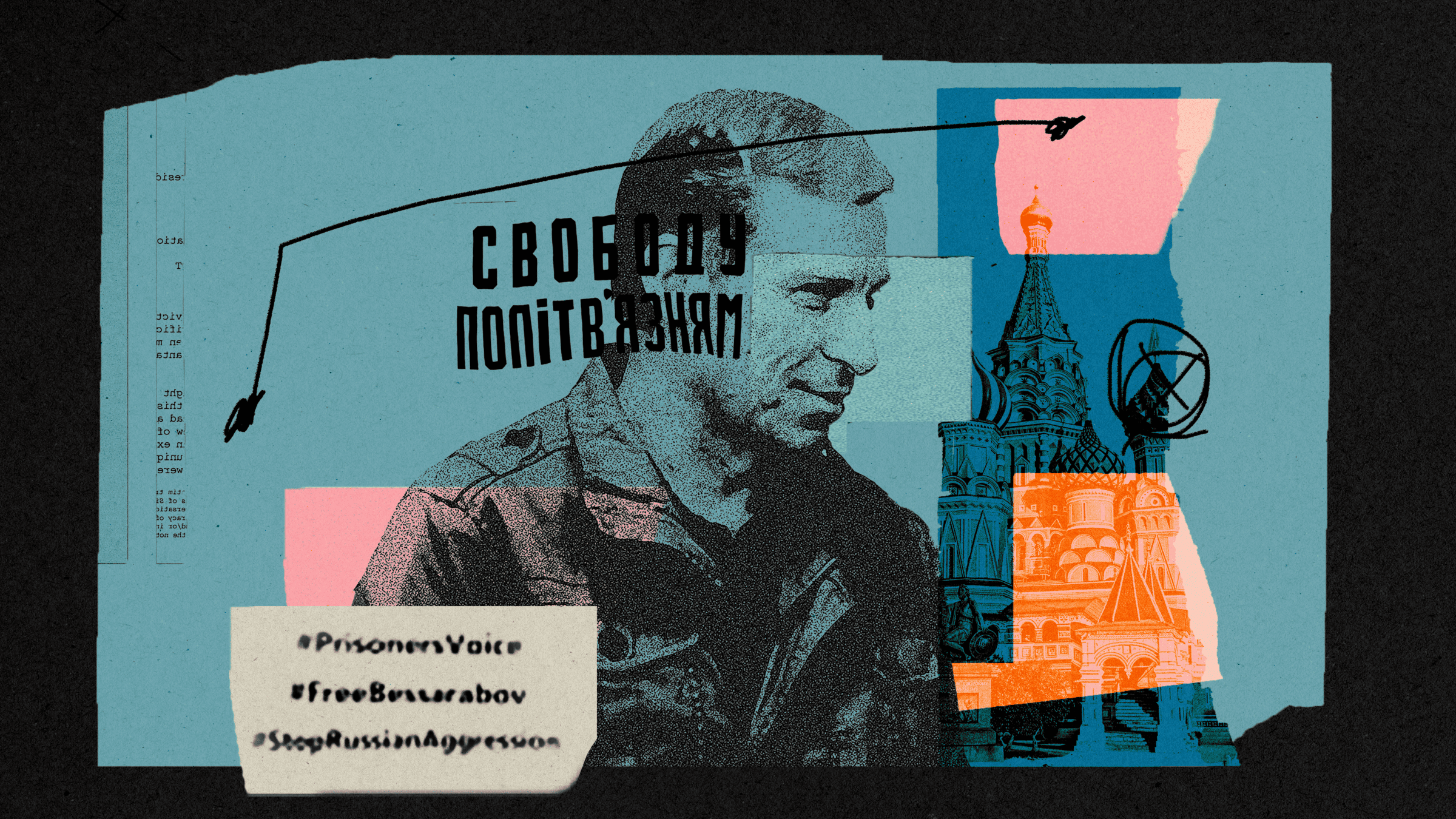

Oleksiy Bessarabov worked as a correspondent for the Glavred news agency. Under the pseudonym Oleksiy Streletsky, he published in the journals Maritime Transport, Black Sea Security, and Mirror Weekly.

Since 2009, he has been the deputy editor-in-chief of the journal Black Sea Security and an expert at the NOMOS Center for Assistance to the Geopolitical Problems and Euro-Atlantic Cooperation of the Black Sea Region Studies.

Bessarabov was detained in November 2016. In April 2019, he was sentenced to fourteen years in a high-security prison for allegedly “preparing sabotage by an organized group” (Part 1, Article 30; Part 2, Article 281 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation) and for the “illegal acquisition and storage of explosives or explosive devices, committed by an organized group” (Part 3, Article 222.1 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation).

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

Though born in Novgorod, Oleksiy Bessarabov always considered himself a Sevastopol native. His parents moved to Crimea in 1977 when he was just one year old.

In ancient times, it was Chersonesus; in the Ottoman Empire—the Crimean Tatar settlement Ak-Yar, and in Russia—Sevastopol. It lies on the shores of over thirty Black Sea bays, making it a port city. It is also the main base of the Black Sea Fleet.

“All the boys in Sevastopol wanted to become sailors,” laughs Pavlo Lakiychuk, a close friend of Bessarabov’s. They first met at the Pavlo Nakhimov Sevastopol Naval Institute. Getting in was no easy task—the number of applicants was enormous.

“You couldn’t miss Oleksiy,” Lakiychuk recalls about their first meeting. “He had his own stance. His intelligence was enviable. Not to mention the high honors diploma from school and a series of other awards.”

Bessarabov was fluent in English and constantly improved it. After graduating in 1999, he was assigned to Odesa, where he worked as an interpreter between teams during international military exercises. The multinational exercises “Sea Breeze” were held under the Memorandum of Understanding and Cooperation in Defense and Military Relations between the U.S. and Ukraine, dating back to 1997.

Around that time, Bessarabov began writing for the international journal Maritime Transport about foreign fleets, as well as long-distance and coastal ships, including military vessels.

The decision to become a sailor, made by Bessarabov at the age of eighteen, was somewhat romantic. He dreamed of the sea and was passionate about his work. He rented accommodations from an elderly woman in Odesa, dedicating all his time to military service. He didn’t care much for himself.

Reflecting on their cadet years, Bessarabov’s friend Lakiychuk compares their training: “I trained on Soviet training ships, while Oleksiy trained on boats. For example, they rowed from Sevastopol to Varna along the Black Sea coast on boats with sails. I laughed,” Pavlo recalls. “If someone rows such a distance like a Cossack, then they are certainly a sailor.”

But the sea journey came to an end. After a few years of military service in Odesa, Bessarabov developed health problems.

“You should listen to your mother,” sighed Lakiychuk. “Eat porridge for breakfast and borscht for lunch. This lieutenant’s life in a foreign city did him no good. Oleksiy developed a stomach ulcer. Later, he transferred to Sevastopol to work at the Navy Headquarters. But he didn’t serve for long.”

In 2005, Bessarabov was discharged due to health issues.

Black Sea security

Bessarabov understandably received the news of his discharge with bitterness, though he knew military personnel often face similar circumstances. After achieving the rank of captain-lieutenant in reserve and ending his military career, he decided to fulfill his second dream—to become a journalist.

In 2005, he enrolled in the undergraduate program at the Institute of Journalism at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. He began working as a correspondent from Crimea for the publication Glavred, where he published a series of articles under the title “Explosive Crimea.” Ukrainian journalist and PEN Ukraine ambassador for Bessarabov, Myroslava Barchuk, explains that Bessarabov wrote not only about pro-Russian organizations in Crimea and the threats and political consequences of the presence of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol but also about business scandals and corruption related to it. For example, he wrote about housing construction for Russian military personnel in Sevastopol, funded by Luzhkov [a Russian politician who served as mayor of Moscow from 1992 to 2010].

After working at Glavred, Bessarabov accepted the position of deputy editor-in-chief of Black Sea Security, a journal dealing with global energy issues, international security, and Euro-Atlantic integration in the Black Sea-Caspian region.

By 2011, Bessarabov foresaw the occupation of Crimea.

“Today, Russia does not apply military-political pressure on Ukraine, preferring to seize its strategic assets and economically absorb it. However, due to the presence in Ukraine of forces (including major owners) dissatisfied with the prospect of losing not only profits but also national sovereignty, a shift in Ukraine’s political course cannot be ruled out, which Russia would not be able to accept, considering it a threat to its national interests. This course of events could lead to conflict, possibly involving force,” he wrote in a 2011 article in the Razumkov Center’s compilation “Crimea, Ukraine in the Coordinates of Black Sea Security.”

Bessarabov studied Russia’s violations of the bilateral Black Sea Fleet agreements. For example, in October 2013, he wrote an extensive analytical piece in Mirror Weekly about the illegal introduction of military equipment into Sevastopol, including a new armored personnel carrier, a raid and rescue tug, a diving vessel, and a “caravan of other vessels” of the Black Sea Fleet. He also wrote about Russia’s violation of border control by the Smetlivy guard ship and how the Kremlin began exerting economic pressure on Kyiv, transitioning to open forms of confrontation with the direct involvement of the Black Sea Fleet.

Bessarabov was convinced that Russia’s leadership would continue to actively use the Russian Black Sea Fleet in its strategic game. “Today, Moscow is confident that all the cards are in its hands and ‘pushing’ Kyiv won’t be difficult,” he wrote in Mirror Weekly. “The important thing, according to the Kremlin’s calculations, is to skillfully conclude the years-long maneuver. Hence the brazen behavior of the Russian navy on Ukrainian soil.”

The journalist questioned: How will Ukraine, and its political leadership, act when facing the bluff and threats from its northern neighbor?

A step into the abyss

What happened next is well known. At the beginning of 2014, troops, transferred from Russia and the Crimean bases of the Black Sea Fleet, occupied the Crimean Peninsula without insignia, taking advantage of the political transition in Ukraine following the Euromaidan.

Russia began repressing all dissent. Crimea was in chaos.

“It was spring. My son was finishing the tenth grade,” recalls Lakiychuk. “I approached home, and there was a Bars armored vehicle standing near the entrance. Inside were Buryats drinking and turning the machine gun around. I thought to myself: What should I do?”

The tension increased. The Black Sea Security editorial team, including Bessarabov, was under surveillance. The journal’s editor-in-chief, Serhiy Kulyk, a former military officer who was head of the internal policy department at the Sevastopol City Administration, decided to destroy the journal’s archives for the safety of the authors and editors. The team gathered at the office and debated whether to burn or shred the documents. They shredded them.

Many received warnings from “sympathizers” that it was time to leave. “That was the last day when hryvnias were still in use,” recalls Pavlo. “You could take a bus to a place where a car would pick you up.”

At the bus station, the Lakiychuk family was seen off by close friends, including Bessarabov and their mutual friend Volodymyr Dudka. “They understood that staying in Crimea wouldn’t end well, but they hoped they could walk between the raindrops,” Lakiychuk muses.

But Bessarabov’s mother was ill. Where could he move her? She was like a child who constantly needed care, medication, and regular checkups from psychiatrists and neurologists.

Bessarabov traveled to Kyiv. There, he met with his friend, Pavlo Lakiychuk. He said he planned to sell his home and move his family to Kherson. “He had a Gordian knot of problems to untangle,” explains his friend.

Since his school years, Bessarabov had been the pillar for his mother and sister as he grew up without a father. Now, he had additional responsibilities for his wife and son.

“I thought he would manage to do everything,” Lakiychuk shares. “At that time, I was already at the Globalistics Center ‘Strategy XXI’ in Kyiv, and I invited him to help revive Black Sea Security.”

“I’ll sort out my problems, and then…” Bessarabov would say.

But “then” never came.

The “legend” of three friends

In political prisoner cases, Russian security services often invent and fabricate “evidence” to create a realistic narrative. This time, they lucked out with a plot, as the “Sevastopol saboteurs” case involved three friends with shared histories.

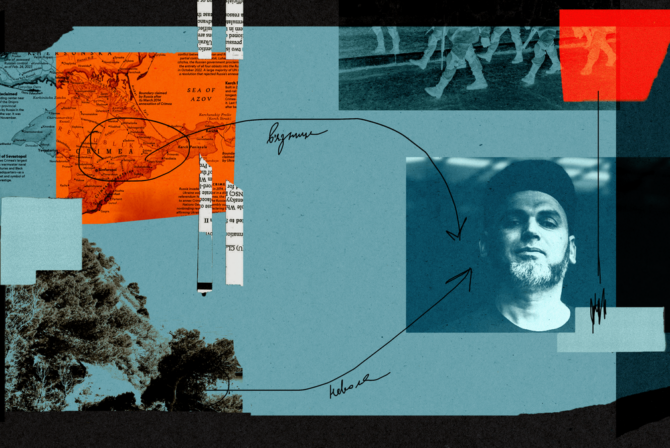

Pavlo Lakiychuk had known Volodymyr Dudka since their student days at the Kaliningrad College. Dudka served in the Ukrainian Navy and commanded the ship Simferopol. Later, Lakiychuk introduced Volodymyr to Bessarabov and Dmytro Shtyblykov, who worked together at Black Sea Security, writing about security measures in the region and the fleet.

Despite Shtyblykov working as a warehouse clerk after the occupation, Bessarabov doing odd jobs, and Dudka working in emergency services, this trio fit well into the narrative created for them. To arrest them, the FSB organized a whole special operation.

On November 9, 2016, as Bessarabov was leaving a hospital where he was undergoing treatment, he was dragged into a black Barguzin van with tinted windows and taken to an unknown location.

At the same time, the FSB officers seized Shtyblykov, the director of international programs at the NOMOS center, in the middle of a street. In a published video, three security officers can be seen jumping on him, twisting his arms, pressing him against the hood of a black car, and then packing him inside.

The following scenes are ridiculous: Among the “evidence” found in Shtyblykov’s house were a Ukrainian trident, weapons (though experts could immediately tell it was airsoft equipment), supposed explosives, and—the icing on the cake—a business card of Dmytro Yarosh, the leader of the Right Sector. A business card of the head of a right-wing party in the home of a person of Jewish origin? The “evidence” was publicly mocked.

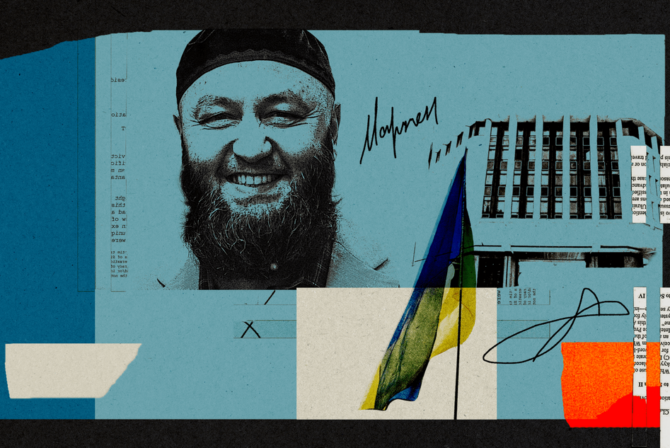

On the same day, Dudka, a military pensioner, was abducted near the building where he was renting an apartment.

“You’re guilty, or I’ll kill you.”

For a week after the arrest, there was no information about the accused. They were hidden from their families and lawyers.

Later, it was discovered that Bessarabov, Shtyblykov, and Dudka were in the Simferopol detention center. The occupation authorities accused them of “illegal possession of weapons and preparing sabotage as part of an organized group.”

FSB officers dragged Bessarabov and the other defendants one by one into the basements of private houses in Simferopol. They tortured them with electric shocks and forced them to give testimonies on camera.

Dudka was taken to the forest.

“The FSB turned on the electric dynamo machine and connected it to his fingers so that no visible signs of torture would be seen on video,” says Maryna Trofymenko, Dudka’s partner. “He was on the verge of death. The FSB officers stopped the torture when he lost consciousness. They had to call an ambulance to revive him.”

Maryna recalls that in the recorded videos, she immediately noticed that Dudka’s facial expressions and voice tempo were unnatural. The whole family unanimously remarked on his odd facial expressions, unusual words, and phrases. “I know how he speaks and commands, but in this video, he behaved like a different person. And Oleksiy Bessarabov was completely pale,” recalls Maryna.

Before the FSB removed the video, specialists from the Crimean Human Rights Platform managed to analyze it.

“It was clear that the video was staged,” explains Olha Skrypnyk, head of the Crimean Human Rights Platform. “There’s no lawyer in the recording nor visible officials conducting the interrogation—this is a violation. Additionally, it’s evident that the person is under the influence because they hold a posture that makes it difficult to move, indicating torture.”

The fact of torture was confirmed by other lawyers working on the cases of Bessarabov, Dudka, and Shtyblykov. “Experts stated that, judging by their dilated pupils, psychotropic substances were administered to the suspects. We don’t know which ones exactly. For example, those that deprive sleep. But we do know for sure: All three were threatened with harm to their families,” says Skrypnyk.

The human rights activist emphasized several violations during the investigation.

The first is the violation of the right to legal assistance, as there were obstacles preventing Bessarabov from being represented by an independent lawyer under contract.

The second is torture, illegal investigative methods, and the use of physical and psychological violence.

The third is the staged video interrogation. This violates the presumption of innocence and, accordingly, the right to a fair trial.

Due to torture, Shtyblykov agreed to “cooperate with the investigation.” He was sentenced to five years in a high-security prison. Meanwhile, the court proceedings in the cases of Bessarabov and Dudka, who refused to plead guilty, lasted more than two and a half years.

After the first trial, the Sevastopol city court could not issue a verdict and returned the “saboteurs’ case” to the prosecutor’s office for “correction of deficiencies.”

Only in August 2018 did the Sevastopol city court re-examine the case. Appeals from the defendants about falsification and gross investigative violations were dismissed by the Russian Supreme Court.

Both Bessarabov and Dudka were sentenced to fourteen years in a high-security prison.

“I’m waiting.”

Bessarabov is held in Kochubiyevsk Correctional Colony No. 1 in the Stavropol region. Communication with him is extremely difficult because his family does not stay in touch. After his imprisonment, his wife, an associate professor and candidate of technical sciences, was fired from Sevastopol State University. Human rights activists have testimonies that the family was pressured and intimidated.

On November 8, 2021, Shtyblykov was supposed to finish his sentence in the “Crimean saboteurs” case. He was set to be released. However, on that very day, he was transferred from Lefortovo detention center to Rostov-on-Don, where the Southern District Military Court opened a new case against him, this time on charges of “state treason.”

The verdict—another fourteen years and six months in a high-security prison and one year of restriction after serving the sentence.

“He’s held under the harshest conditions,” says Maryna Trofymenko, Dudka’s partner, who is in contact with Shtyblykov’s family. “According to his wife, he is kept separate from other prisoners. He’s not allowed to communicate or make phone calls. Even parcels, which others receive once a quarter, he can only get once every six months. He is isolated from everyone.”

Both Shtyblykov and Dudka have lost so much weight they are unrecognizable.

Dudka faces problems with medical examinations. He has several illnesses. To see a doctor, he has to wait two days in line, but what can be done when he has high blood pressure? Dudka’s son, Illia, sends him medications, but it’s more self-treatment than professional help.

“A few days ago, his blood pressure was 190 over 100,” Trofymenko says. “Nothing helps. His stomach hurts. For eight years, he hasn’t had proper treatment,” she adds. “I no longer believe that anything will change.”

Bessarabov suffered a severe case of COVID-19, and new illnesses have erupted in addition to the previous ones, including a significant decline in his vision.

Regarding Bessarabov’s detention conditions, Trofymenko describes them as “prehistoric”—an outdoor toilet, the cold. The barracks consist of “squads,” with a large number of people sleeping there: bed-cabinet-bed-cabinet.

Recently, Bessarabov was forced to make a choice: Either he gets a new sentence and goes to the front, or he starts working in a prison enterprise. He chose the latter. Now, he works as a shoemaker.

Last year, Trofymenko managed to talk to Bessarabov on the phone. He said that after studying English, he took up German. He asks for textbooks to be sent to him.

Every evening, prisoners must sit and listen to “political information” from Russian TV channels. When I asked if Bessarabov knew what was happening in Ukraine, Trofymenko noted: “Both Bessarabov and Dudka understand that everything said on TV should be interpreted as the opposite.”

Balancing act

Taras Malyshevskyi, the acting Consul General of Ukraine in Rostov-on-Don from 2018 to 2022, fought for the right to visit Ukrainian political prisoners. According to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, he has the right to use his mandate to protect Ukrainian citizens. Under the consular agreement between Ukraine and Russia, Russia was supposed to notify his office within five days of the detention of a Ukrainian citizen.

“Of course, they didn’t notify us within five days,” Malyshevskyi says. “And they didn’t grant access to the detainee in the early stages of detention when the person is under pressure and tortured just to confess. Only later do they allow access to lawyers, consuls, and so on. But by then, it’s too late because the person has signed a document confessing to something they didn’t do.”

After four years and lengthy correspondence with the Federal Penitentiary Service, Malyshevskyi managed to visit Bessarabov more than ten times. However, the conversations took place through glass, and the entire conversation was conducted via an intercom and recorded.

“These meetings are a kind of linguistic balancing act,” recalls Malyshevskyi. “I speak eighty percent of the time, and the prisoner speaks twenty.”

The logic is this: What if the consul starts a campaign to defend the prisoner? Writes letters to Moscow, the Russian ombudsman, the local prosecutor, citing the prisoner’s complaints? Then the prison administration will remember: Oh, where’s that video of the consul sitting with our prisoner?

“Often my task was not to cause harm or provoke inspections of the prisoner,” Malyshevskyi admits. “At the same time, the very fact of meeting with the consul is a kind of protective mechanism and a message—‘you are important to us.’”

This message, according to the ex-consul, is directed both at the prisoner and the prison administration because when they see that so much attention and care is given to a person by one of the main officials of Ukraine in Russia, they treat him more cautiously.

After the imprisonment of Oleksiy Bessarabov, Volodymyr Dudka, and Dmytro Shtyblykov, the case of the “Sevastopol saboteurs” gained publicity, and the prison knew that Bessarabov was “not ordinary.”

However, with each passing year, hope for Bessarabov’s release faded. His name was on the so-called “Sentsov List”—a list of Ukrainian political prisoners held in Russia and in temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. At one time, this list also included the Ukrainian director and writer Oleh Sentsov, who was a political prisoner in Russia from 2014 to 2019. Many political prisoners from this list have been released, but not Bessarabov.

In May 2021, ahead of U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Kyiv, Bessarabov wrote an open letter to him. He writes, “Despite the fact that my name, along with the names of dozens of other political prisoners, appears on the lists of human rights organizations such as Freedom House and Memorial, we are nearly forgotten. Only our loved ones, friends, and colleagues remember us. We are forgotten because the issue of Crimea is not discussed in either the Normandy format or the Minsk talks.”

In August of the same year, Antony Blinken wrote a response to Bessarabov. However, Malyshevskyi notes that Bessarabov could not see the original letter. The ex-consul could only show him a copy through the glass. “It was a nice moment, although I couldn’t give him the original of that letter. It would have brought even greater aggression upon him. No materials can be passed.”

In his response, Antony Blinken writes, “The United States will continue to call on Russia to release all Ukrainian political prisoners it unlawfully holds so that you and other political prisoners can return to freedom, reunite with your loved ones, and continue your lives in a sovereign, democratic Ukraine.”

The last time before Ukraine and Russia severed diplomatic relations, Malyshevskyi visited Bessarabov in January 2022. The consul recalls that during their meetings, he could feel Bessarabov’s unbreakable spirit.

“He held himself with dignity and confidence, firmly,” says Malyshevskyi. “He always looked good and had a clear mind. We talked about geopolitics and what was happening outside the colony. After all, Oleksiy is an analyst. He has a very keen sense of the political situation in the world.”

And therefore, he knows that he will inevitably return to his beloved sea.

This text was written in July 2024.

Translated by Yevheniia Dubrova.