In 2019, organizers of the literary contest “Crimean Fig” received their first submission from behind bars. It was titled “My Deportation,” though it did not describe the events of 1944. Instead, the subheading read: “(written at a pre-trial detention center).” The text was compelling, like the script of an action movie. It was fast-paced and quite laconic but rich in detail, including a special glossary of jargon used by Russian courts and prisons. The text was solid. However, it’s very unfortunate that it needed to exist in the first place.

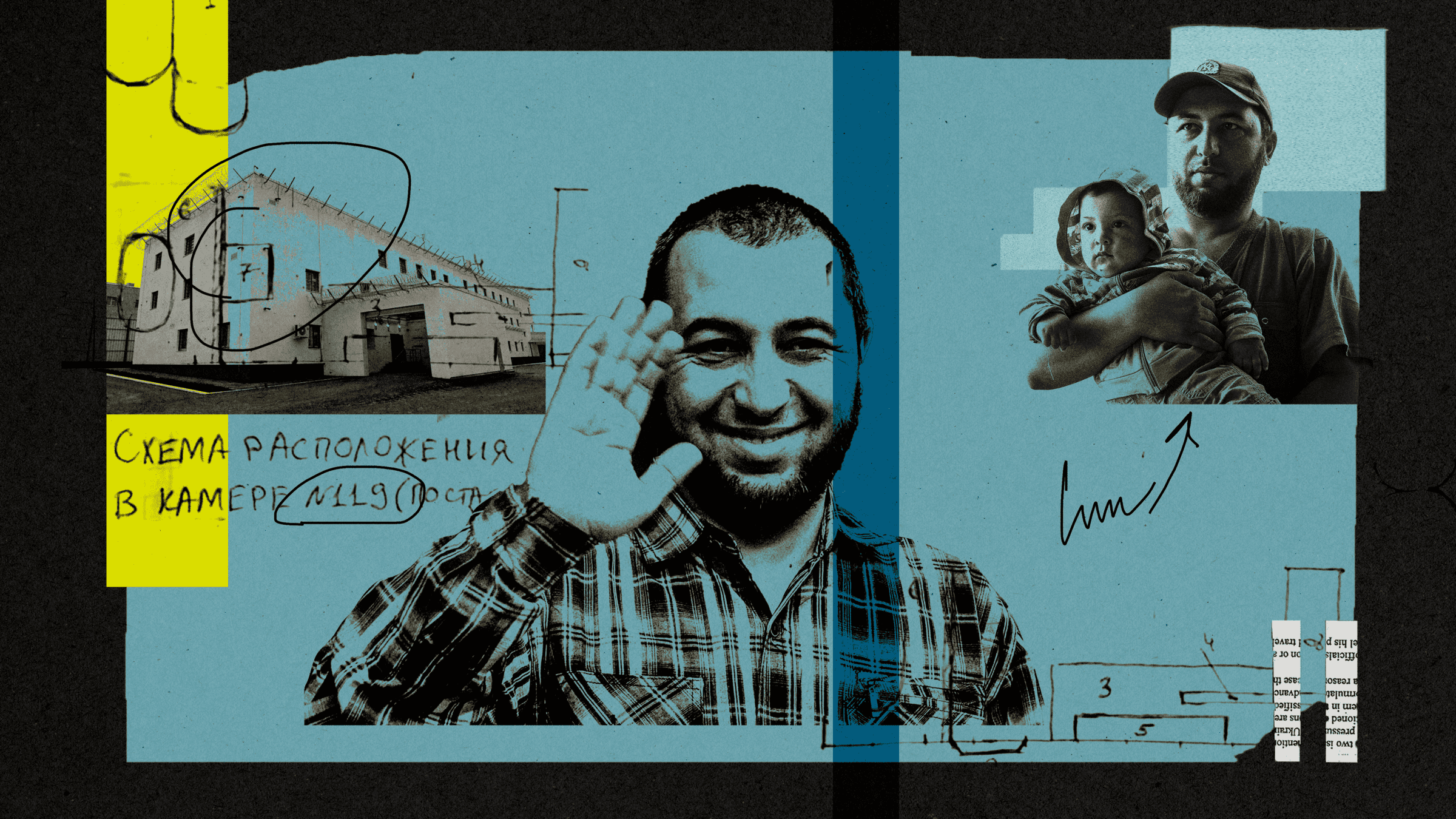

The text was written by political prisoner Osman Arifmemetov, who described how security officers had detained him and sent him to prison in March 2019. On November 24, 2022, he was sentenced to fourteen years in a penal colony.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

Deportation

Between 4 and 5 a.m. on March 27, 2019, Crimean human rights advocate and lawyer Liliya Hemedzhi received a call from the wife of Ruslan Suleymanov, one of her former defendants. She informed her that their house was being searched. Hemedzhi and her husband, also a lawyer, immediately went to their house in the village of Strohanivka in Simferopol district. That morning, thirty Crimean Tatar homes were searched. Three of them—the houses of Ruslan Suleymanov, Osman Arifmemetov, and Remzi Bekirov—were in the same neighborhood. All of them were friends and lived on Azatlik Street, which translates from Crimean Tatar as “Freedom Street.” They were all engaged in citizen journalism, even though none were trained journalists.

Arifmemetov is a mathematician by training. Before his imprisonment, he tutored math and programming. He loves working with children and knows how to do it well. He began engaging in citizen journalism only when Russia started pushing professional journalists out of the peninsula, and many media outlets and reporters were forced to leave. Arifmemetov says that his story began long before 2014—in 1944, the year when Crimean Tatar people were deported.

This is how Arifmemetov, in prison, explained why and how he and his friends were fighting: “The events of May 18, 1944, became part of my biography. […] In places of exile, a non-violent route toward returning to our homeland was preferred, and a sense of responsibility for others was shaped. […] Since the political situation in Crimea changed, repressions against my people were launched. To prevent the comeback of 1944, passionate young people, together with the older generation, entered another chapter of the historic fight.”

There are only smartphones and tablets in our hands and generosity in our hearts.

Many people who care about this cause remember a video Arifmemetov recorded in March 2017. In it, next to the building of the ‘supreme court,’ Russian security men are seen taking Bilial Adilov, an activist and imam [leader of the Muslim community], to a blue van with tinted windows and plates that lacked identifying numbers and driving him away. “There—one more of our brothers is being taken away. Unidentified people. In balaclavas. Introduce yourselves. Who are you?” Arifmemetov says in the video. Then, viewers see a person in uniform and a balaclava knocking the phone out of his hands. “What if you’re stealing it!” Arifmemetov yells.

Lutfiye Zudiyeva, a citizen journalist and human rights advocate, says this episode is significant not just in the context of Arifmemetov’s activities. She strongly believes that this video launched the coordinated efforts of media activists.

The point is, Zudiyeva continues, the blue Volkswagen with tinted windows and plates that lacked identifying numbers was often seen in Crimea at the time. Security men would grab people right off the street and shove them into the van. Quite a few people disappeared like that. Arifmemetov was afraid the same would happen to Adilov. So, he ran after the security men, streaming video and providing a running commentary. Zudiyeva says that after this video, public activists realized they should stream videos because they weren’t edited and served as direct evidence of what was happening. Moreover, the media, both Ukrainian and foreign, eagerly republished these streams. Security officers, in turn, realized they could not go unnoticed when abducting people.

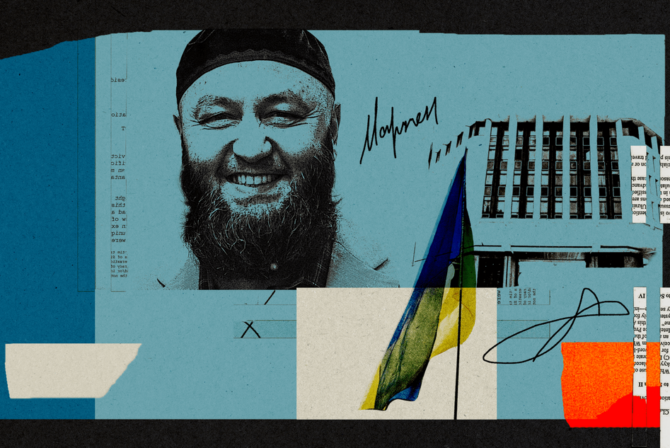

Arifmemetov began filming searches in Crimean Tatar homes in October 2016. It started with the searches of the homes of his fellow villagers, brothers Teymur and Uzeir Abdullayev, houses next to one another that share a common yeard. Arifmemetov knew for a fact that they weren’t criminals or terrorists as they were accused. In February 2017, Arifmemetov filmed a search at the home of Marlen Mustafayev, an activist and metalworker by training. Speaking with the Crimean Human Rights Advocacy Group, he described how upon hearing an order “Keep working! Keep working!” one of OMON agents twisted Arifmemetov’s arm so hard that the tablet he was using to record the video almost fell out of his hand.

Soon after, Arifmemetov and nine other activists covering these events were detained for five days. They spent the entire day of their detention without food and water in an unheated bus.

“Brutal detention, harsh conditions, and transporting people to the ‘trial’ without food and water is a systemic practice of the occupation authorities,” remarks Olha Kuryshko, Deputy Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. “Any complaints about the process or conditions of detention are either ignored or receive a brief response: ‘Inspection conducted; no violations identified.’ I know of an attempt to appeal against the actions of the administration of the detention center where Crimean Tatar activist Dzhemil Hafarov was held. He had a health condition that required hospitalization and systemic professional treatment. The administration gave no instructions for his treatment, though. Hafarov’s health deteriorated, and on February 10, 2023, he died at the pre-trial detention center.”

On October 11, 2017, Arifmemetov filmed the aftermath of a search conducted at the home of entrepreneur Tymur Ibrahimov. At the time, Ibrahimov had just brought his wife and their newborn baby home from the maternity hospital. The search took place with a ten-day-old baby in the house.

Arifmemetov was known for his efforts to help political prisoners and their families. He frequently traveled to Rostov-on-Don, leaving early in the morning to stand in line, deliver packages to fellow Crimean Tatars at the pre-trial detention center, and then attend court sessions. If you trace the stories of Crimean Tatar political prisoners, you’ll see that before finding themselves behind bars, most of them supported others by raising awareness, assisting political prisoners and their families, delivering packages to prison, and helping with money, food, and home repairs. Security men often warned them openly: If you film a search at a friend’s home, you’ll be next.

On March 27, 2019, Arifmemetov’s house was also searched. At the time, no one was home: his wife Aliye and their children were visiting her parents, and Arifmemetov was in Rostov-on-Don for a court session to support “the first Simferopol group”—five Crimean Tatars who had been detained by Russian security officers in October 2016 and charged with involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. When Aliye and the children returned home, they confronted a distressing scene. The house was a mess, with everything from the basement—bicycles, strollers, pickles—piled up by the front door. The security officers, unable to break down the door, had just cut it out with a grinder, along with the frame.

The following day, Arifmemetov, with his two colleagues—Remzi Bekirov, a historian and tour guide, and Vladlen Abdulkadyrov, a cell phone repair technician—were detained by FSB officers at a McDonald’s in Rostov-on-Don. As Arifmemetov later described in his letter and short story “My Deportation [written at a pre-trial detention center],” an entire group of armed security men was involved. They forcibly twisted the activists’ arms behind their backs, handcuffed them, and led them to a van. Once inside, they were “told to kneel face down on the floor between the seats.” They took them away, beating them both on the way and after stopping at some asphalt lot. Arifmemetov lost consciousness from the violence.

“In its reports,” Kuryshko notes, “the UN General Assembly often highlights the torture of people detained and held in custody in the temporarily occupied territory of Crimea, as well as the inhuman and degrading conditions of detention. As far as illegal searches at the homes of Crimean Tatars are concerned, international law prohibits arbitrary or unlawful interferences with privacy and family and guarantees the inviolability of the home. However, this doesn’t deter the occupation authorities.”

To explain; to show

In his letters, Arifmemetov repeatedly stresses two key points. First, he traces his story back to 1944. There’s a reason that he titled his short story about his arrest “My Deportation.” The deportation is a milestone from which thousands of threads stretch from 1944 all the way to the present day, affecting the life of the Crimean Tatar people even after the mass resettlement in their homeland. Abundant stereotypes about Crimean Tatars and the disdain that other residents of Crimea often show toward them are linked to it, too.

Arifmemetov’s mother, Emdiye Arifmemetova, recalls that even as a child, her son never hesitated to speak out against injustice toward his people.

For example, when he was a teenager, he overheard a teacher telling a group of younger kids that Stalin was right to deport the Crimean Tatars. Arifmemetov reported this to the school principal, who called the teacher to his office. On another occasion, a Russian language teacher told his class, which included three or four Crimean Tatars, that May 18 was not officially recognized as a day of mourning and should not be commemorated every year. Arifmemetov also spoke out against this claim.

Suleiman Mamutov, an expert with the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, offers this insight: “True, during the active resettlement of kırımlı in the 1990s and early 2000s, such situations were common and reflected a sort of ‘norm’ in Crimea. The rhetoric of local authorities and the society, widely disseminated through Crimean publications with large print runs, systematically downplayed the tragedy of the violent banishment of the indigenous people and justified the crime committed by the Soviet government. In some articles and ‘letters to the editor,’ Sürgün—the genocide of 1944—was almost depicted as a fascinating voyage across Siberia and Central Asia, with Moscow as a caring ‘tour operator’ that provided for the ‘tourists.’ The narrative even suggested that the party leaders were acting out of the most benevolent intentions—to protect Crimeans from the bloody revenge of the Red Army for supposed mass treason and collaboration with the Germans.”

Once, as an adult, Arifmemetov was speaking Crimean Tatar with a friend on the bus when some passengers around them began to complain about why they spoke a language others didn’t understand. Arifmemetov explained that they had the right to speak their own language, especially in a private conversation. Some passengers quieted down, while others made an even bigger fuss. In the end, Arifmemetov felt compelled to remind everyone who had arrived to the peninsula and whose lands had been occupied.

Arifmemetov had a talent for explaining things clearly. His mother, Emdiye Hanim [an honorific meaning Mrs.], shares this story. One day, a wealthy man asked Osman to tutor his son for a math exam. The boy wasn’t eager to study, so Osman asked his father why he was wasting his money on tutoring if his son hated the subject. The man said, “Please don’t count my money—just make sure my son is prepared to apply to university.” Osman continued his tutoring and told the boy: “Imagine you’re going to be the manager of a construction company.” He then drew a building, explained its features, and said, pointing his finger: “To build this, you’ll need to understand how to calculate this, this, and this, and you’ll have to know your way with tangents and cotangents.” Osman’s clear explanations sparked the boy’s interest, and he became enthusiastic about his studies.

Since childhood, Arifmemetov has hoped to be understood and firmly believed in the importance of speaking out even when it seemed that people didn’t understand you. This belief has given root to another one he always mentions in his letters and speeches: Crimean Tatars fight for their rights through legal, non-violent methods. Like many other Crimean Tatar political prisoners, Arifmemetov was arrested on charges of “involvement in the activities of a terrorist organization,” so he finds it necessary to repeat over and over: “I’m not a terrorist or a criminal,” “I reported on injustice, and for this, they labeled me a terrorist,” and “Russia is using its anti-terrorist and anti-extremist laws as a tool to suppress non-conformity and active civic engagement.” In November 2022, following his sentencing to fourteen years in a penal colony, Arifmemetov said in his final statement: “In three decades I lived in Crimea, I don’t recall ever hearing about a single terrorist act or terrorists—until Russia arrived with its inhumane laws and yearning for the past.”

Several Ukrainian and international organizations have confirmed that Arifmemetov’s imprisonment is politically motivated. These include the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, the European Parliament, the OSCE, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and a Russian organization—Memorial Human Rights Center.

Victoria Amelina: “I no longer have a voice.”

In 2021, PEN Ukraine and Human Rights Center ZMINA launched a project in which prominent Ukrainian writers served as ambassadors for journalists who were political prisoners arrested by Russia in the occupied territories. The writers worked to raise awareness of their cases by talking about these prisoners of conscience in their interviews and public speeches both in Ukraine and internationally.

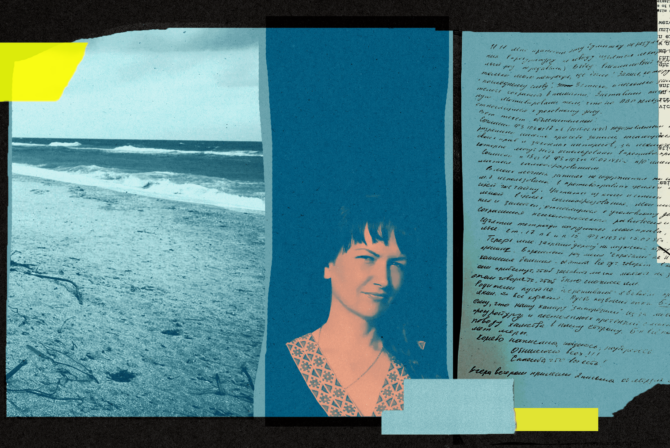

Victoria Amelina was Arifmemetov’s ambassador. She mentioned him in her speeches at various public events, reminding opinion leaders about the human rights situation in Crimea.

During the full-scale war, Amelina published Arifmemetov’s letter to her on her Facebook page [see Quotes], introducing it with the following remarks:

“I was meant to be his voice, but I no longer have a voice. Whatever I say about Osman—political prisoner, husband to Aliye, math teacher, citizen journalist, activist with Crimean Solidarity, and father of two children, who will soon be slapped with a long sentence by Russia—will be drowned out by news of bombed cities, countless deaths, and the urgent calls for weapons and sanctions.

“Osman Arifmemetov clearly has no idea that I’m helpless when it comes to raising awareness about his case and his situation. Yet, it’s just as clear that he never gives up. That’s why he writes letters to me from his solitary cell in the pre-trial detention center.

“I don’t know how to help him. But here’s his letter. Please remember Osman Arifmemetov and other political prisoners from occupied Crimea.”

In late June 2023, Amelina was fatally wounded in a Russian Iskander missile strike in Kramatorsk. While she was in the ICU, Arifmemetov sent a letter to her and her family from prison, hoping she would stay strong and recover.

On July 1, Amelina died of her injuries at a hospital in Dnipro.

Where does Osman find his strength now, almost five years into his imprisonment?

In one of his letters to the community, Arifmemetov shares that attending trials has actually become a source of joy for him, as it’s his chance to see his “much-loved cemaat” [community]. He writes, “And when sadness comes, I have tea with the sweets you send me with such care.” Solidarity and mutual support are very typical for the Crimean Tatar community, and they help people endure. In the same letter, Arifmemetov mentions that people helped his family back home replace the water filter and insulate their house, as well as bringing them groceries.

However, these everyday comforts are not Arifmemetov’s primary source of strength.

As his letters reveal, he’s also inspired by the sense of continuity in his struggle.

He knows that his grandparents and parents fought for the cause in exile, and he now continues the fight side-by-side with his own generation. In a letter from 2020, on the eve of the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Crimean Tatar Genocide, Arifmemetov writes: “During my five days in solitary confinement at Simferopol Central Prison, I often thought about the peaceful resistance that began in exile. How many activists who fought for our return to Crimea were held in basements and then disappeared? They must have paced those damp cells from wall to wall just as I do now. A new generation has stepped up to continue the cause of the national movement’s veterans. Today’s youth have made a conscious choice.”

Human rights advocate Liliya Hemedzhi says that Arifmemetov’s greatest support comes from his faith. “Finding themselves in prison, people crystallize their beliefs even more,” she notes. “They draw parallels with stories from the Quran, such as that of Yusuf’s madrasa.” [A madrasa is a Muslim religious school. In Islam, Yusuf is a prophet whose story is told in Sura 12 of the Quran, which has 111 Ayahs (verses). In Christianity, he is known as Joseph, and his story is told in Genesis 37:2–50:26. Finding himself in prison due to false accusations, Yusuf-Joseph accepted this as God’s blessing and continued to preach. That’s why prison is called “Yusuf’s madrasa,” a ‘school’ where one can achieve spiritual growth.—TU]

Arifmemetov steadfastly defends his rights and stands his ground, continuing the fight. He is preparing a cassation appeal [an appeal against the decision of the court of second instance brought before the Supreme Court] against his verdict, filing lawsuits to have his name removed from the offender registry—where he is labeled as promoting and practicing extremist ideology—and tirelessly documenting all the violations committed against him.Can these actions have a positive outcome for prisoners? According to Hemedzhi, such actions can help prevent further violations by security officers. Second, in rare cases, these requests have been approved. For instance, when Server Mustafayev filed a lawsuit after his hair clipper was confiscated, he was provided with a new clipper (and asked to withdraw his lawsuit). Third, there’s also a practical benefit: filing lawsuits means an opportunity to meet with your lawyer. Finally, the process of filing lawsuits, calling for justice, and raising awareness of one’s situation is significant in itself. As a Crimean Tatar saying goes, “Tama-tama göl olur,” or “Drop by drop—a lake forms.”

This principle motivates many Crimean Tatars to engage in citizen journalism, remain active, and fight for their rights despite the risks.

This text was written in January–May 2024

Translated by Hanna Leliv

Колажі Анастасії Струк. У зображеннях використано ілюстрацію Марії Глушко, а також світлини Кримської солідарності, Османа Аріфмеметова й Тараса Ібрагімова.