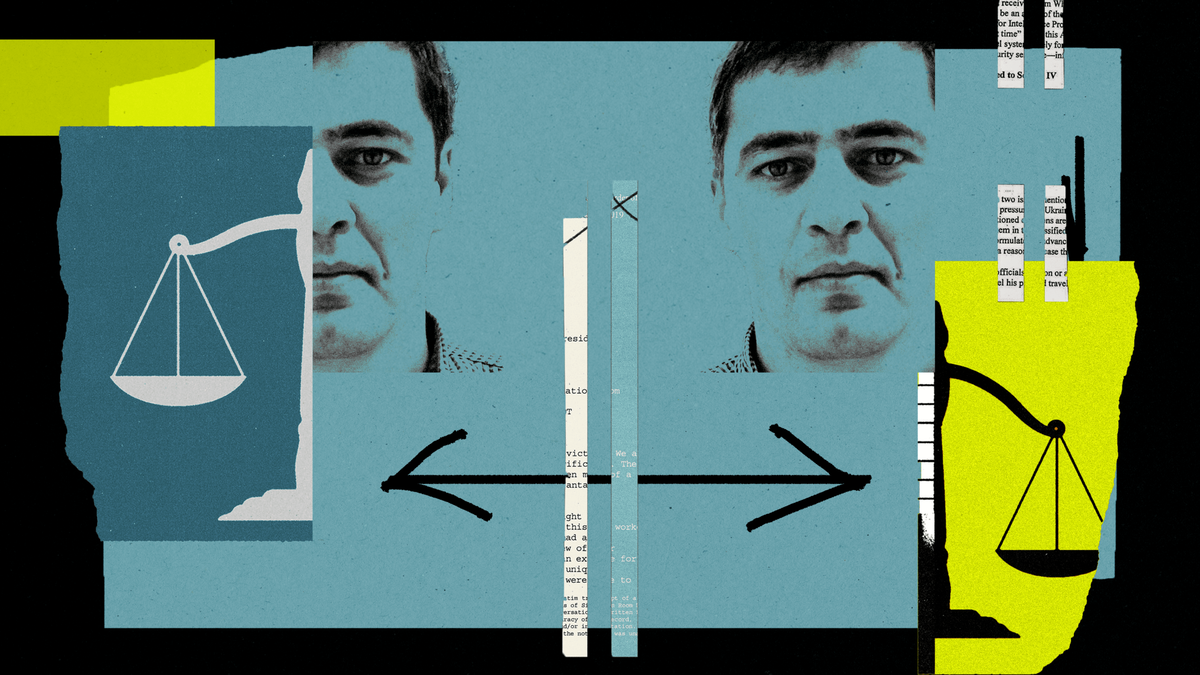

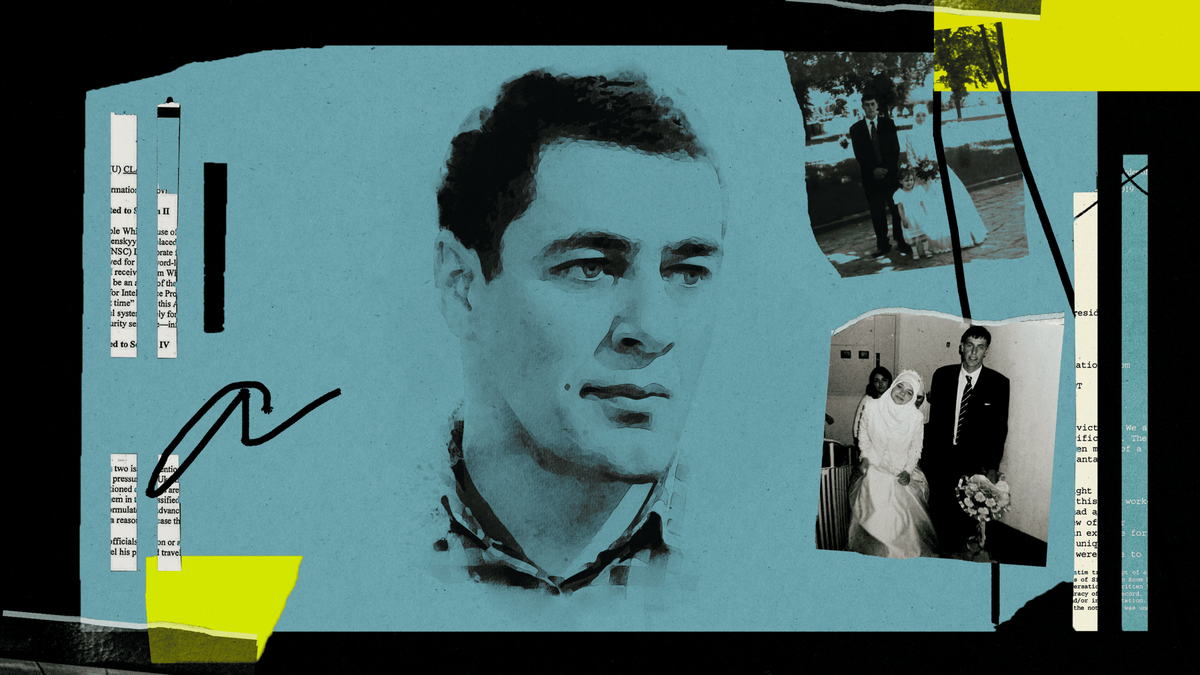

Amet Suleimanov was born in 1984 in Uzbekistan to a family of deported Crimean Tatars. In 1991, they returned to Crimea, settling in the Bakhchysarai district. Amet attended a madrasa in Simferopol but had to discontinue his studies due to heart disease. Later, he trained as a carpenter at the construction school in Bakhchysarai.

Amet and his wife, Lilia Liumanova, are raising four sons: Ibrahim, Mukhammad, Mansur, and Seit-Osman. Following the Russian occupation of Crimea, Amet became a citizen journalist for Crimean Solidarity, a human rights group.

In 2020, he was arrested on charges of “participating in the activities of a terrorist organization,” a common accusation used by Russian authorities in occupied Crimea against Muslims, often linked to Hizb ut-Tahrir, an organization banned in Russia. Amet’s case is unique, though. During the trial, the Russian court issued the first-ever ruling on house arrest in a Hizb ut-Tahrir case. However, in 2023, a rigged trial resulted in a final verdict, sentencing Amet to twelve years of imprisonment, including three and a half years in a high-security prison. This sentence is incompatible with Amet’s health condition—he suffers from arterial and mitral valve insufficiency and urgently needs a heart valve replacement.

§§§

With this narrative portrait, we launch a special project dedicated to the free voices of Crimea. This series of stories about journalists, now political prisoners, is a joint initiative of PEN Ukraine, The Ukrainians Media, ZMINA, and Vivat, supported by NED.

§§§

“He was the one for me.”

“Sincere and straightforward,” says Lilia Liumanova about her husband, Amet Suleimanov. Lilia and Amet met at the wedding of mutual friends, where they both served as witnesses. “I was eighteen,” Lilia recalls. “Education was my main priority, and I never even thought about having relationships. But Amet was persistent, and I agreed to go on a date… After the very first date, I knew he was the one for me. He impressed me with his outlook on life and family.”

It was during that first date that they also talked about their families. “He grew up without a father. It was just Amet, his mother, and his younger brother,” Lilia explains. “My own father passed away very early. I was only eleven at the time, so I know all too well what it’s like to grow up without a dad. I understood that Amet learned to shoulder responsibility for his family at a young age. And I also knew he was very reliable, someone I could always count on. That’s exactly what happened. Since I was eighteen, I’ve been used to talking everything through with Amet and making all our decisions together.”

“Amet is very calm and sensible,” Lilia says. “Honestly, I didn’t quite like it when he was fixing things around the house. He’d take his time and do it very slowly and thoughtfully, considering every detail down to the smallest nail. His calm meticulous approach is a defining characteristic of his personality.”

“Dad’s not a mum”

Amet Suleimanov’s role as a loving father is integral to his identity. Together with Lilia, they are raising four sons. Lilia recalls that her first pregnancy had a tragic end. “The first time, I had a miscarriage,” she says. “We were young and didn’t fully grasp everything, but coping with the loss was still very hard for me. The second time, I gave birth to our oldest son.”

Amet took care to create good memories for his sons. Lilia says, “Sometimes, he’d call after work and just ask me to make the kids ready without explaining anything. I would get them dressed and wait until he arrived. Then he’d take us, let’s say, to the beach to breathe in the fresh air and so the kids would have some fun—skipping pebbles in the water or just running around. And it didn’t matter that it was winter.”

In each letter he sends her, Amet asks Lilia about the boys and their interests—he wants to stay connected with their lives and know how they are changing as they grow up. He encourages Lilia to take them out to add variety to their daily routines and allow them to unwind.

While Amet was the primary provider for the family, Lilia focused on raising the children. However, during the house arrest, their roles shifted. “I became ‘the ministry of foreign family policy,’” Lilia quips, “while Amet took care of the children at home. He would joke that ‘dad’s not a mum,’ but he handled everything adeptly. He even mixed bottles for our youngest and found individual approaches for each of the older kids. Amet truly pulled his weight, and I can see that now. We were always aligned in our approach to parenting. Even if I was mistaken, he never contradicted me in front of the boys. It was only later, in private, that he’d tell me I could’ve acted differently.”

When they put him on house arrest, Amet took measures to shield his children from trauma. “The kids were deeply concerned when they saw the bracelet on his leg,” Lilia recalls. “For the first month or two, Amet slept in the same bed with them. He must have sensed that a long separation lay ahead and wanted to spend as much time as possible with his sons. It was likely his presence that prevented our sons from being too traumatized by his imprisonment.” Back then, his children were unaware of the meaning of “preventive measures” or “house arrest.” However, now, his eldest son, aged fifteen, independently follows all news related to his father.

During his house arrest, Amet took proactive steps to prepare his family and household for his impending absence. He taught Lilia how to use tools and clean the pump in case it got clogged. Now, their sons help Lilia around the house, knowing exactly where to find brushes, paints, wrenches, and other essentials.

After marrying, Lilia did not work outside the home. “I suggested sending the kids to nursery school and searching for a job,” Lilia says. “But Amet simply asked if there was anything else I needed. Since our family had all our necessities covered, I just stayed at home. Our children didn’t attend nursery school because I cared for them while Amet handled grocery shopping and other errands. This arrangement gave me time to take our sons to speech therapy sessions and clubs and do other activities.”

Suleimanov’s arrest changed their life drastically. Lilia had to look for a job to support the family. “I still work at a jewelry shop,” she says. “I’ve taken on the responsibility of earning money. At first, Amet found it strange to be at home. He didn’t even know how to cook. But he quickly learned, and the meals he prepared sometimes tasted better than mine. He even built a tandoor oven and learned how to bake in it. When I bought a large, sixteen-liter cast-iron pot, he learned how to make pilaf. His pilaf tastes so good that I stopped cooking it myself—I’ve even forgotten how to do it. I tried once after they took Amet away, but all I ended up with was a disgusting rice porridge instead of pilaf.”

A citizen journalist

Lilia recalls that Amet has always been an active citizen and community member. “He never turned down anyone who needed help,” she reflects. “People could call him anytime, day or night, and he’d respond. Sometimes, it even made me angry. I wished he could leave it all behind after returning home from work and put his phone down, at least for a while. Following his time at the madrasa, Amet and his friend organized collective prayers at the mosque every Friday. Our community placed great trust in him. They even entrusted him with naming babies.”

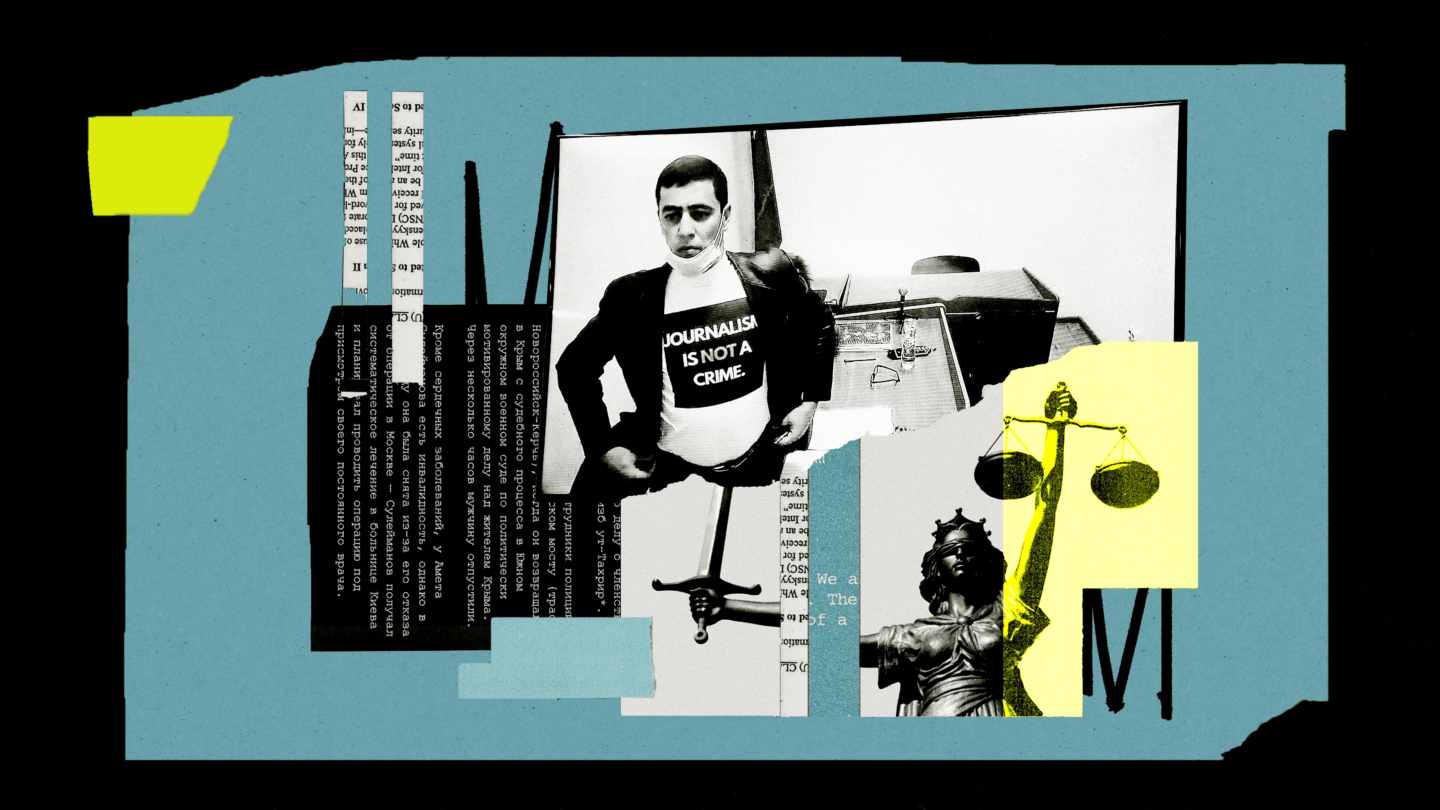

Even after 2014, Amet’s dedication to helping others remained steadfast. However, the nature of the required help changed. Amet helped families whose husbands were unlawfully detained as members of the “Bakhchysarai groups.” He brought food to detainees at the pre-trial detention center, helped their families with household tasks, and offered rides to wives when they needed to run errands. “And then, he just couldn’t stay at home—he simply grabbed his phone and went to document the searches,” Lilia recalls. “That’s how he became a citizen journalist.”

In Ukraine, the term “citizen journalist” gained prominence primarily in relation to events unfolding in Crimea.

“Our organization, KrymSOS, started to talk a lot about it around 2015–2016, which means that citizen journalists first emerged in the peninsula after the events of spring 2014,” explains Tamila Tasheva, co-founder of human rights NGO KrymSOS and Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

She stresses that citizen journalists play a crucial role when independent professional journalism faces threats. “In February and March 2014, Russia’s military invasion of Crimea was accompanied by an attempt to exert total control over the media landscape,” Tamila Tasheva recalls. “In particular, they pressurized journalists—from Crimea, mainland Ukraine, and abroad—who sought to document the events in Crimea. Occupation troops, ‘law enforcement officers,’ and infiltrators abducted and persecuted journalists covering the occupation of Crimea. Starting from May, the pressure on local media intensified to the point where they were compelled to flee the peninsula.” Entire editorial offices had to relocate, so by 2015, the pool of professional journalists in Crimea had shrunk to zero.

“In such circumstances, the search for alternative sources of information became imperative,” Tamila Tasheva says. “And these sources were people who simply documented events using their cell phones and live-streamed house searches and human rights violations. They promptly shared this content online. Therefore, citizen journalists served as our sole firsthand source of information regarding the realities unfolding in Crimea. These people lacked professional backgrounds or training in media. They had never worked in media or had any experience in media management. Technicians, vendors, software engineers, former professors—everyone simply grabbed their phones and assumed this role.”

Lilia Liumanova reflects on how each filmed house search and documented arrest took a toll on Amet’s health. “It was tough,” she acknowledges. “After each incident, Amet would just lie in bed, anxious and sad. I could see that these events weighed heavily on his heart.”

“It’s just not possible”

The onset of Russia’s occupation of Crimea was a challenging time for the family, even though they hoped things would get settled soon. Lilia reflects on her belief at the time, saying, “I thought, in the twenty-first century, it’s just not possible.” She adds, “I suppose it was our way of resisting a reality we didn’t want to accept.”

Later, Lilia’s older sister decided to leave Crimea. “There’s a nine-year age gap between us, and we’ve always shared everything—clothes, interests, childcare,” Lilia says. “She was like a second mother to me. It was incredibly hard for me when she, her husband, and daughters departed for Lviv. Amet could see that, so in 2015, he bought tickets, and I went to Lviv with our two sons to visit my sister. I was pregnant at the time. Then Amet joined us, and we returned home together.”

Before the occupation, Lilia and Amet only heard about religious persecution in Russia through the news. However, after the beginning of the Russian aggression, this grim reality became theirs as well.

Amet was first detained in the fall of 2017. This occurred after he filmed security men near the home of Seiran Saliev, an activist of Crimean Solidarity, during his house search. On that occasion, the occupiers imposed only an administrative fine amounting to fifteen thousand rubles.

The arrest

In October 2019, Amet was detained after attending the trial of one of the illegally arrested Crimean Tatars. Six months later, their house was searched for the first time. That same day, on March 11, 2020, the Federal Security Service (FSB) conducted house searches and detained five Crimean Tatars. All of them were charged by the Russians with involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir. Amet is illegally charged under Part 2 of Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (see “Involvement in the activities of a terrorist organization”).

Tamila Tasheva underscores the systematic nature of illegal and politically motivated persecution in occupied Crimea. “Within the peninsula, the occupiers target several groups of Ukrainian citizens. Foremost among these are the Crimean Tatars. As of early January 2024, 204 politically motivated criminal cases have been opened in Crimea, with 123 of them directed against Crimean Tatars.”

Why do the Russian occupiers target this particular community? According to Tamila Tasheva, the reason is that Crimean Tatars are the most united group and the least loyal to the Russian Federation.

“This became apparent right from the beginning of the temporary occupation,” she says, “when Crimean Tatars disregarded the ‘referendum’ and other ‘election processes’ in the peninsula. Russia identified Crimean Tatars as a risk group for its presence in Crimea and subsequently initiated systemic ethnic and religious persecution. However, above all, the occupiers target Crimean Tatars as politically active Ukrainians—citizens of Ukraine who openly reject the occupation and assert Crimea’s belonging to the Ukrainian state.”

In this context, Suleimanov’s case stands out as unique. He is likely the only detainee facing similar charges who was placed under house arrest instead of in a pre-trial detention center. Why did this happen? It was somewhat miraculous: the rigged Russian court took into account his heart disease, which posed a risk to his life.

The trial spanned three years. “All court hearings took place online,” Lilia recounts. “However, they attempted twice to bring Amet to the district court in Rostov-on-Don. Then, on October 29, 2023, the verdict was delivered—twelve years of imprisonment, with three and a half years to be served in prison and the remainder in a high-security facility. We filed an appeal, of course, but the verdict remained unchanged.”

The Suleimanov family had anticipated this outcome. “We knew who we were dealing with,” Lilia remarks. “Amet told me right away to take off the rose-colored glasses. So, we packed his things while the trial was ongoing. We kept them at home, away from the eyes of our children and parents. When the judge announced the twelve-year sentence, I immediately called my friend and asked her to bring the bag.”

Initially, they planned to take Amet directly from the courtroom to the pre-trial detention center. However, the couple was able to return home after the proceedings. They had to wait for the necessary documents with a wet stamp to arrive from Moscow. So, they got to spend another two months together at home in Bakhchysarai.

The prison

Amet was taken away during the holy month of Ramadan, just as the family was preparing for the night prayer and a meal. “When we heard the doorbell, we immediately knew they had come to take him,” Lilia recalls. “He asked me to take the children into another room. The two men who arrived spoke to us with lowered eyes. They knew our family very well because they’d been coming over to check on the house arrest formalities for the past three years. They knew they were taking away an innocent person.”

Amet asked his wife not to allow the men inside. “I brought all the necessary things out into the yard,” Lilia says, “and Amet went to change. He did so in front of the open window in the children’s bedroom so the men could see from the outside what he was doing.”

—He didn’t say goodbye to the children, simply leaving with two bags, asking Lilia to reassure them that he would return soon. Amet also asks Lilia not to bring the children to visit him in prison for fear of traumatizing them or himself.

They took him to Simferopol, initially to Pre-Trial Detention Center No. 1 and later to Pre-Trial Detention Center No. 2. Lilia recounts the exceptional cruelty of the personnel at these facilities. For instance, Amet was prohibited from lying down or sitting. From six in the morning until ten at night, he was forced to stand. This prolonged standing caused his legs to swell, as his lawyer observed.

For two months, Lilia had no means of contacting Amet. “They refused to deliver our letters to him,” she explains. “I believe it’s a form of psychological pressure. Only lawyers were permitted to visit, and only for fifteen minutes. They purposely delayed these visits until the end of the working day, providing a pretext to cut short their communication.”

After two months of silence, she received Amet’s first letter from Pre-Trial Detention Center No. 2 in Simferopol. Though infrequent, the letters did manage to reach her. Then, Amet was transferred from Simferopol to Russia. “He wrote to me about the pain he felt being taken away from Crimea,” Lilia shares. “He wondered if he would ever see his beloved Crimea again. He said how hard it was to be forcibly removed from his homeland.

It resonated with the experience of deportation that our older generation endured.

His imprisonment, like that of other Crimean Tatars, is also a form of deportation.”

Currently, Suleimanov is in Vladimir, so packages must be addressed to the Vladimir Central Prison. However, correspondence is conducted electronically. Lilia explains: “I send him my letters and pay for a blank form for him. Amet then writes a letter by hand, scans it, and sends it to me as a .PDF through the Zona Telecom application.”

In a recent letter, Amet warned her that he wouldn’t be able to stay in touch for a while because he was being taken to the hospital for a medical examination and wouldn’t have the opportunity to receive or respond to letters. Lilia recalls that his lawyers had previously submitted a complaint. “Due to his health condition, they had no right to place Amet in either the pre-trial detention center or prison,” she explains. “The court hearings were supposed to take place in Crimea, but since Amet was transferred to Vladimir, they must now be held there. The first hearing was scheduled for December 20, 2023, but it was postponed because Amet was allegedly taken for a medical examination.”

At the end of 2023, in the last days of December, Lilia still didn’t know Amet’s whereabouts. “He said they wouldn’t take him far,” she says. “But I haven’t received letters from him since December 11, although my cousin did get a letter a bit later. It means he was still in prison for some time. And then, he was apparently taken away because neither our relatives, nor the lawyers, nor I received any messages from him.”

Lilia believes that the goal of the medical examination is to demonstrate that Amet is healthy and that the Russians did not violate any regulations with their imprisonment verdict. “However, even before that, Amet had filed a petition demanding that all medical documentation be retrieved from his case file.”

Another challenge is accessing medication. Lilia explains that it’s incredibly difficult for her to provide Amet with the necessary medicines. “At first, a friend of ours attempted to deliver the medication to the prison, but they refused to accept it in person. So, I sent it by mail, but a month later, the package was returned to Crimea. This means that since September, Amet has not been able to take the medication he needs. They provide him with some pills in prison. He told me their names. However, one of the drugs does not work for him. What’s more, they don’t show him the labels, so he doesn’t even know for sure which medicine he’s given. But he has no choice but to take it.”

An essential aspect of this case is the decision of the UN’s Committee against Torture passed in February 2023. Lilia specifically mentions three paragraphs containing demands addressed to Russia. “The first demand is to refrain from passing a verdict due to the defendant’s health condition,” she explains. “The second one is to conduct a comprehensive examination of his health. And the third one is to provide medical treatment and surgery. Russia has disregarded this document issued by the international organization.”

Lilia saw Amet for the last time in September 2023. They spoke through a glass partition for two hours. “We managed to obtain permission for a brief visit,” Lilia says, “and to give him a package—twenty kilos of food. In a year, Amet is allowed a total of two short visits and one three-day visit, along with one twenty-kilo package and one parcel. I have used up all of that—except for a three-day visit and a parcel—back during his imprisonment in Crimea.”

Lilia recalls that Amet didn’t appear well during their meeting. He exhibited symptoms of cardiac insufficiency. “Bruises under his eyes, shortness of breath,” she describes. “All the efforts we made in Crimea, all the medications I’ve tried to provide him with—none of it is a treatment but merely a postponement, an attempt to support his body. A heart valve replacement is the only solution for Amet.”

P.S. As I was finishing writing this essay, Lilia, her two older sons, and her brother-in-law set off for a three-day visit with Amet. The visit started with coffee brewed in a jezve that Lilia had brought along from home. Amet hadn’t had coffee in a year. He joked with the kids and marveled at how much they’d grown since he last saw them. He also gave them some much-needed advice and caught up on the news about relatives, friends, and neighbors. Amet had lost ten kilograms and his health had declined significantly. “Amet told me in detail what happened to him over the past year,” Lilia says. “It became clear from what I heard why he had gotten worse.”

This text was written in December 2023–April 2024

Translated by Hanna Leliv