On January 5, 2023, sotnyk [1] with the call sign “Kryvonis,” who commanded the most triumphant battle of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UIA) against NKVD in the Carpathians, celebrated his 100th birthday. He had served one of the longest sentences in Soviet camps. “For heroism demonstrated in the fight for Ukraine’s independence, outstanding personal achievements in the building of Ukrainian statehood, and years-long fruitful public activity”: the decree of the President of Ukraine dated October 14, 2022, conferred the Hero of Ukraine title upon Symchych, the first member of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army to be awarded it while still alive.

His life is a story about the rivers of blood, the desire to die an honest death, the betrayal and falsification of court cases, the revenge for the deportation of Crimean Tatars, the origins of the present-day Armed Forces of Ukraine—and also about the one he has been calling his ‘sweetheart’ his entire life.

§§§

The Ukrainians Media is an award-winning independent media company focusing on high-quality, long-form, and visual journalism. Our mission is to foster positive social changes in Ukraine.

This story was created thanks to the support of our readers. Please join The Ukrainians Community on Patreon and help us publish more important and interesting stories.

§§§

Myroslav Symchych lives in Kolomyya, in a cramped apartment lined with decorative plates, books, and portraits of his wife, sons, grandchildren, himself, and his brothers-in-arms.

We visit him on the eve of his centenary. People keep dropping by, wishing him happy birthday over the phone, and sending emails. Myroslav can barely hear or see and mostly keeps to himself. But we talk a lot with his wife Raisa, 85, who waited for her husband to return from prison for long 18,5 years (he served 32,5 years in total—one of the longest sentences in Soviet camps).

Myroslav Symchych was born near Kolomyya—in the Carpathian village of Vyzhniy Bereziv, established by warriors in the times of Galicia-Volyn Principality. He has opryshky [2] in his family, and his uncle was a Sich rifleman [3]. Myroslav went to school in a neighboring village established by Ridna Shkola learning society. The language of schooling was Ukrainian, which was unusual for the territories under Polish control. He was reading a lot about the Khmelnytsky Uprising and dreamed of becoming a Cossack. Later, when the authorities forbid him to return to the west of Ukraine after his first imprisonment, Myroslav would settle down in Zaporizhzhia—closer to Khortytsia island. After finishing school, Myroslav enrolled in Kolomyya Architectural School. In 1941, he joined the youth wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, and in 1943 had his first battle with the Nazis. The boy was trained at the officer training school in the village of Kosmach—‘Banderites’ capital,’ as the Soviet propaganda would later call it. Getting rid of the Germans, the UIA warriors proclaimed the Kosmach Republic, but in 1944, the NKVD death squads entered the village.

Myroslav’s wife, Raisa, clarifies: after Christmas 1945, her husband commanded the battle of Rushir, not Kosmach (Rushir is one of the hamlets in Kosmach). But more about it later—now Raisa is showing us an embroidered shirt, vyshyvanka, that she will gift her husband for his centenary. She has a habit of making gifts like this for his anniversaries every five years.

The revenge

“Soviet bandits fighting with elderly people, women, and children in Crimea were finally punished by courageous Ukrainian insurgents.” The historic revenge that Refat Chubarov mentioned in his commentary for The Ukrainians is the Rushir battle when Aleksey Dergachev, head of the NKVD death squad, was liquidated. A year earlier, he was deporting Crimean Tatars in Crimea and the Ingush and Chechens in the Caucasus.

It is one of the most infamous chapters in the history of NKVD in the west of Ukraine. The facts were classified as top secret, so at first, this battle did not feature in Symchych’s case at all. Myroslav recalls that back in 1945, he reported to his seniors that 200 enemies had been destroyed, while at the trial in 1968, he was told that the actual number was 376. Neither do we know the actual rank of Dergachev: he features in the case as a lieutenant colonel, but according to another version, he was a major general reduced to a lower rank. In one of his interviews, Symchych mentioned another horrible fact: Dergachev’s division was formed of people who lived in orphanages as children—apparently, the cannibalistic authorities thought they’d act more like janissaries and would be less ‘sentimental’ toward evicting and killing people in their own homes.

So, the NKVD death squad was coming to carry out their punitive operation. Myroslav Symchych recalls: “We did not want to engage with the enemy in the village, or they would just burn it down. Hence, we retreated. The Bolsheviks entered the forested outskirts of Kosmach with triumph: they anticipated resistance and did not encounter any. The Russkis went on the loose, robbing people, raping women, and doing other things they were good at. I won’t go into detail, as everyone knows it too well. When the Bolsheviks relaxed, our units encircled Kosmach and started to shoot at them, staying outside the village. They were shooting back, and the battle went on for three days and nights without stopping. Having used up all their munitions, they sent a radio telegram to the division headquarters in Stanislav, asking for reinforcement and warning that they were on the verge of capitulation. Our reconnaissance intercepted that telegram. Stanislav confirmed they’d be sending reinforcement. Our commanders resolved not to let that happen.” (Suchasnist, 2002).

Sotnyk Moroz was wounded in a fight and relinquished command to Symchych. ‘Kryvonis’ found a good vantage spot under the bridge. The insurgents dismantled the bridge and encircled the site in a horseshoe-like shape. “And so, we were just sitting there, getting colder and colder,” Myroslav says. “It was freezing cold like it often happens on Epiphany Day… So cold that even the beech bark was cracking… “Why aren’t you coming, goddamn it,” I thought. “How long do we have to wait?” Finally, the sun rose, as high as two fireplace pokers, as we hutsuls say. And then we heard the vehicles roar.” (Local History, 2010). The trucks with the NKVD squad approached the river and stopped, unable to cross it. “Then they started to jump off the trucks and line up… Once I saw them all standing together, I gave the order: “Fire!”… There was such a ruckus. You could not hear shots—only a complete racket, like in some kind of hell.”(Local History, 2010).

The Soviet court castigated Symchych as a traitor to the motherland. In the early 2000s, he said: “Today, there’s no antagonism between those who fought in the ranks of the Red Army and us. We do antagonize, though, with the ‘heroes’ who served in KGD and Soviet punitive divisions that fought with us. This antagonism will be there for as long as we live.” (Ukraina Moloda, 2003), “For as long as Russia exists, any manifestation of freedom among Ukrainians is interpreted by our eastern neighbor as ‘crime’ and ‘fascism.’” (Istorychna Pravda, 2013).

Ivan Zaluzhnyi, a Red Army veteran, and Myroslav Symchych, a UIA veteran, met at the celebration of the 70th anniversary of victory at the World War II Museum in Kyiv in May 2015.

Symchych said the key task facing Ukraine was to unite the country, while Zaluzhnyi, whose grandson was killed by Russians in 2014, added: “We can do it only now—the east and the west acting together.” Raisa, Symchych’s wife, is also in that photo of reconciliation.

Raisa recalls how her husband was wounded in the Rushir battle: “An explosive bullet hit his right arm. He bandaged it with a handkerchief. After losing too much blood, he fainted. He tried to bear with it for as long as he could, as the battle would’ve been over if his brothers-in-arms had learned that the commander had been wounded. Who would’ve won it then?”

Raisa looks at her 100-year-old husband and says: “He’d take my hand sometimes and shake it as if saying hello. And then he’d say: “What a strong hand! It is you, Ihor?””

Ihor is Myroslav Symchych’s son who enlisted as a volunteer in the Armed Forces of Ukraine after Russia launched full-scale invasion.

Devil’s crack

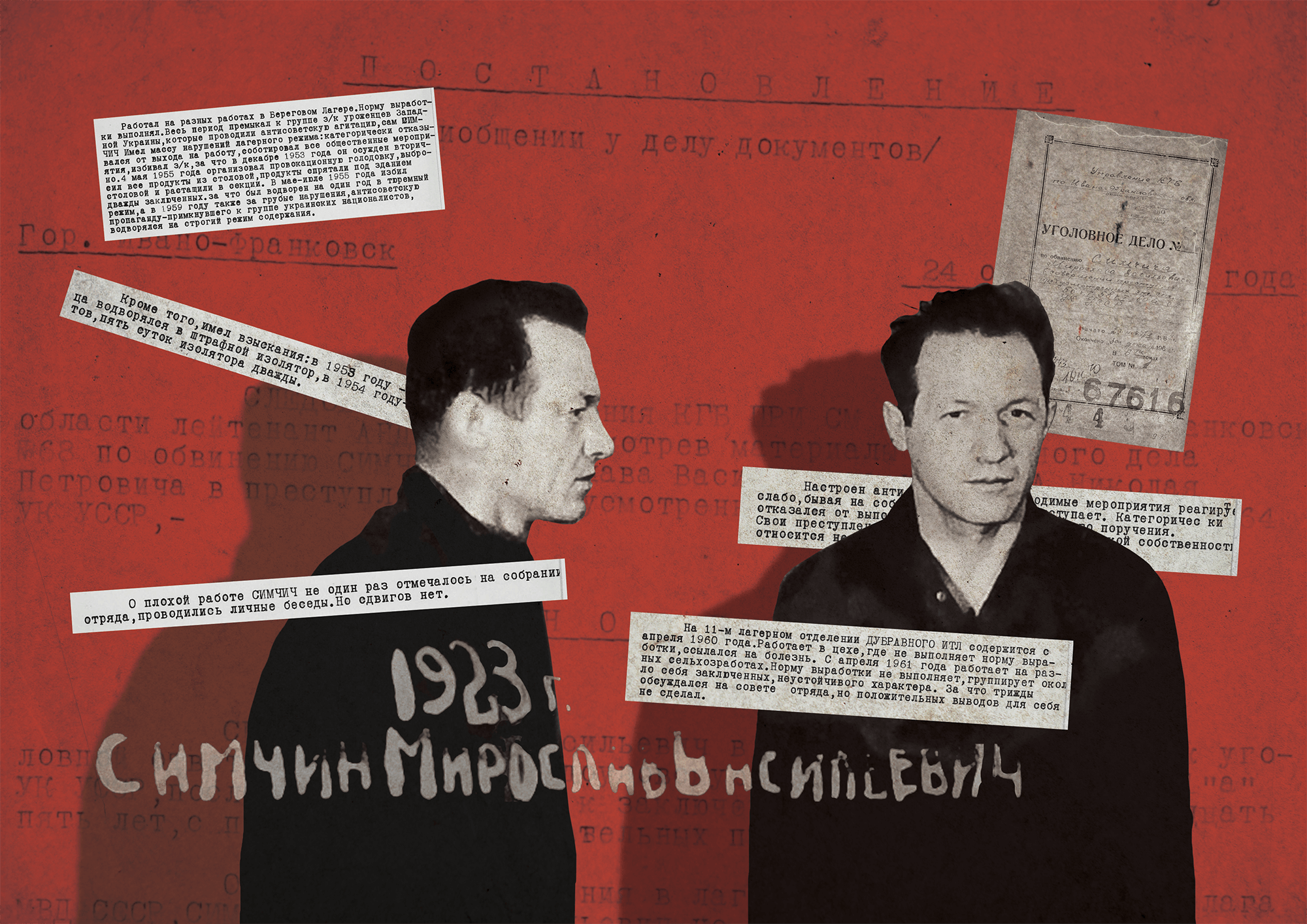

The officer school in Kosmach was called “Forest Devils.” In Kolyma (where Symchych served his sentence, working in a coal mine only to get silicosis), a gorge where the corpses of emaciated political prisoners were thrown en mass was called ‘devil’s crack.’

Myroslav Symchych was detained in 1948: “What was I thinking about when they tortured me? ‘Dear Lord, help me die an honest death!” (Suchasnist, 2002). When they tortured prisoners so hard they fainted, they took their temperature and sent them to solitary confinement if it went above 41 Celsius. When a prisoner came around, a new round of torture would start.

That was the beginning of a story of camp imprisonment, three-decade-long with interruptions.

Myroslav recalls: “Perhaps as many as a million Ukrainians were imprisoned after the war. No one paid any attention to us. We were starving to death, but nobody cared. The West, kneeling before Stalin, ignored the internal political situation in Russia. And then they thought that Russia was just nonsense.” (Suchasnist, 2002).

At the camps, Myroslav shared the bunk with Yevhen Sverstiuk. His fellow prisoners were Ivan Svitlychnyi, Taras Melnychuk, Levko Lukianenko, and Ihor Kalynets.

Symchych considered the Sixtiers as the UIA followers, at the very least. “We appreciated them even more than we appreciated ourselves. Why? Because we were caught in a whirlwind of the fight during the war, when all nations were fighting, whereas they embarked on their fight for a cause when life in the Soviet Union got more or less ‘normal.’ They had higher education and ‘cushy’ jobs. They could live comfortably just like that and not care about the troubles of their people. But instead, they organized rallies and covered them for the whole world to hear. We, members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, could not do that.” (Suchasnist, 2002).

Valeriy Marchenko, a dissident, became a close friend of ‘Kryvonis’ while in prison: “Myroslav Symchych belongs to a small group of prisoners the court found guilty of murder. It is this category of political prisoners that the Russian propaganda outlets refer to when they triumphantly write about ‘elbows deep in blood.’ Back then, those who had not been executed were sent to labor camps where they had to seek redemption for their guilt before the government or, rather, the nation. They declared it just like that: “You will not get an easy death. You’ll toil away until we squeeze all juices out of you!” Realizing how hopeless his situation was, Symchych knew that sooner or later, he’d be blamed for killing the Bolshevik liberators. So fighting remained the only acceptable mode of existence for him. It’s easy to write and talk about alternative truths like this—but they’re hard to implement.”

Marchenko describes an interrogation when an NKVD officer hit Symchych. Symchych, without a moment’s hesitation, hit the representative of the Soviet punitive system back: “Symchych dealt him a heavy, indigestible, unforgettable blow. I once had a chance to watch him during a fight with a morally degraded prisoner. […] The defendant sent the first team of investigators flying across the room. Just like their colleague now, they were lying, touching their noses, jaws, and the backs of their heads. Only after the second team of thrashers arrived, the furious Banderite was tamed. Obsessed with inevitable revenge, they pounded him so hard that he could not get to his feet for a few weeks. Nevertheless, his resistance gave fruit—the investigator never touched him again.”

Successors

Two flags—red-and-black and yellow-and-blue—lie next to Myroslav’s bed. It’s written on the latter: “From the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Thank you, grandpa, for stomping Muscovite rats.”

The connection between the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and the Armed Forces of Ukraine has long been discussed. Mykhailo Stetsyk, call sign ‘Ren,’ the commander of the Carpathian Sich unit who is now defending Ukraine in the south, remembers himself as a boy reading documents and memoirs about the war of liberation in the middle of the 20th century: “It was fascinating to research it since I knew that my maternal and paternal grandfathers and even grandmothers were members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists or the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.”

Mykhailo’s father, aware of his son’s interest, took him—a sixth-grader—to the legendary ‘Kryvonis’ in Kolomyya. The UIA fighter was still keeping an ax in the hallway—he was anticipating the enemy even after Ukraine became independent. Mykhailo asked ‘the man of fire and steel’ questions and double-checked some facts: “I realized I had a unique chance to talk to a representative of a heroic era that humanity had never known before.”

Mykhailo Stetsyk believes that “today’s army is fighting against the same enemy as our predecessors. The same ideological principles. They are fighting for an idea. It often happened—especially in the era of volunteer battalions—that units would adopt the structure like that in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The UIA is a basis, a foundation around which a new generation and a new army have grown.

The insurgent army demonstrated that you could fight against your enemy quite effectively no matter how much they prevail in number and military equipment. Myroslav Symchych is a symbol and an example—from the perspective of practice.

He is a warrior to his bone. People like him must be honored in the modern army to support the fighting spirit, create the military cult, and maintain Ukrainian military tradition.”

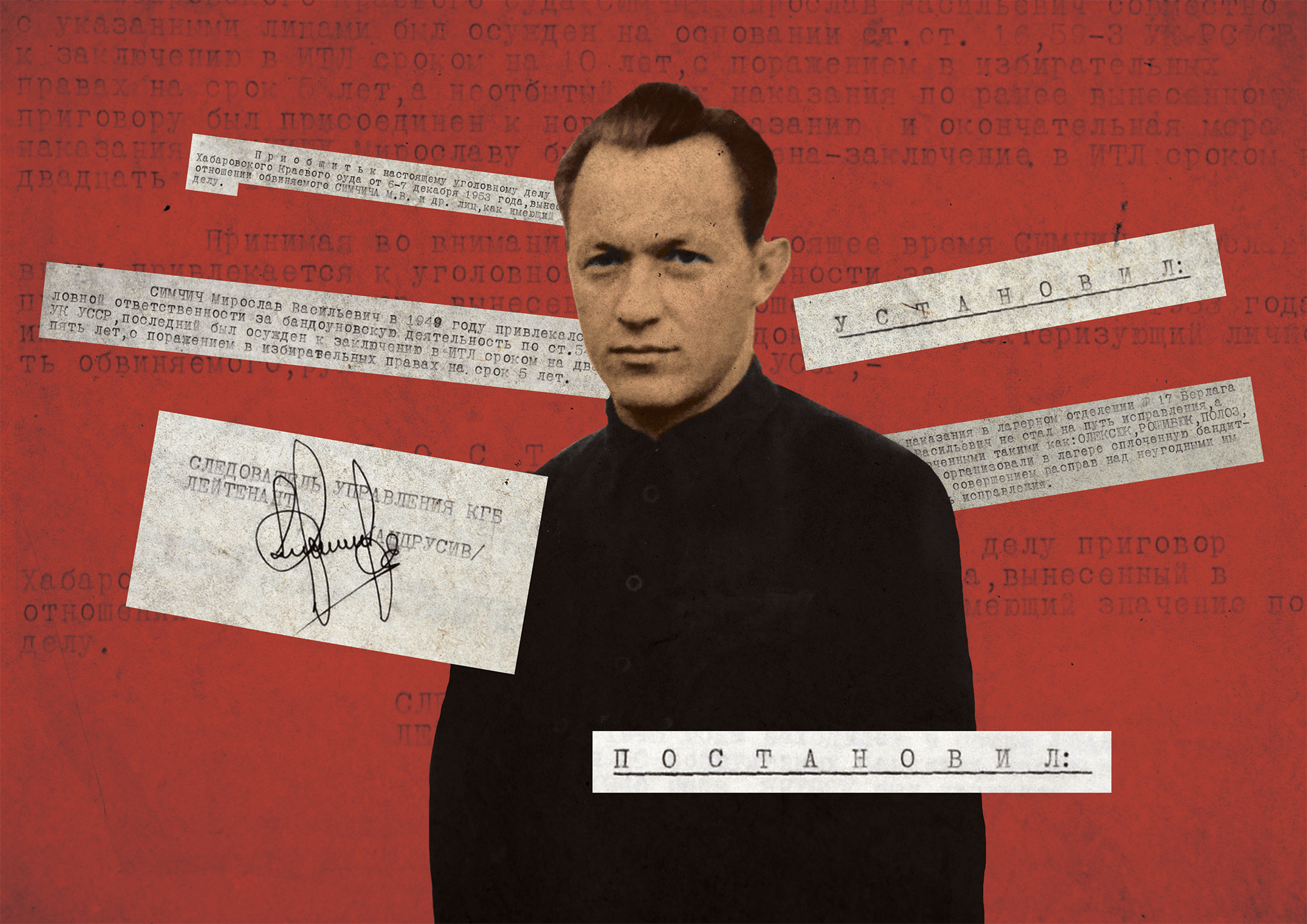

The case

Myroslav Symchych’s case has six volumes or around 2,300 pages: interrogations, the court’s findings about Symchych: “harboring an anti-Soviet attitude, not condemning the crimes committed, refusing to take the path of correction…” The folders also include reports about confrontations and denunciations featuring a hundred of names. Most impressive is seeing the same last names, only with different initials—the residents of neighboring villages and the closest relatives allegedly testifying against each other. It’s a thousand-pages-long thriller whose actual ‘fictionality’ becomes clear only in the last volume, where the ‘witnesses’ who survived until the 1990s retract their testimonies, claiming they either did not know what they were signing or did that under duress. The volume also includes the MPs’ appeal to rehabilitate Myroslav Symchych.

Raisa says she has always known only partial truth about her husband—from letters and random statements from the authorities. She also describes the method of getting ‘facts’: “Once a woman showed me her broken arms — they smashed them in the door to make her give ‘the right’ testimony.” In 1996, ‘Kryvonis’ was denied rehabilitation.

In 2000, Symchych said: “I’m wondering why I am still alive. And then I look back at history and realize there has never been a single war or revolution where everyone would be killed, where God would not leave a small group of people as living witnesses who’d pass the history on to the new generation.” (“Suchasnist”)

Only in 2017, the court ruled that Symchych was eligible to be rehabilitated according to the law rehabilitating victims of political persecution in Ukraine.

A large portion of the facts remains hidden in secret Russian archives. The rank of Dergachev, the number of NKVD officers killed in the Rushir battle, and the details of other actions for which a mature, fire-hardened Ukrainian nation would probably have to ask the innocent victims for forgiveness—all of it remains classified.

Finally, on the last—301st—page in the last volume of Symchych’s case, there’s a copy of the Decree of the Supreme Court of Ukraine’s Plenum dated August 29, 1997, declaring in the name of Ukraine that “the acts he committed were wrongly qualified as high treason.”

Refat Chubarov says: “Myroslav Symchych is a pillar of the nation. His dedication to Ukraine, courageousness, and uncompromising attitude to the enemy have earned him a special place in the collective historical memory of the Ukrainian nation.”

In 1945, Symchych received the news that Shukhevych, supreme commander of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, awarded him the Silver Star, but they did not have time to deliver it to him. Today, though, the Golden Star of the Hero of Ukraine decorates his jacket.

Rayok

Myroslav met Raya in 1963 after he’d served his first sentence—15 years in prison. They lived happily together until 1968, when his comrade betrayed him, identifying Symchych as the sotnyk who won the Rushir battle. Myroslav was sentenced to prison again and again. In 1980, Valeriy Marchenko helped spread the information about the wrongdoings of the Soviet judiciary in Europe, but in 1982, Symchych was again charged with “slander against Soviet governmental and social order” (he was accused of supporting Poland’s Solidarity movement—Myroslav does not deny his affinity for this anti-communist movement).

In conversation with Raisa, we talk about her writing to government leaders and asking them to release Symchych on the grounds of his “old age.” She smiles. Symchych was finally released only on April 30, 1985.

He found a job as a lathe operator in Zaporizhzhia, but the Soviet regime would not let him go. Myroslav recalls that time: “A regional newspaper published a full-page article about me. I was called a ‘fascist,’ ‘a murderer,’ and whatnot in the best traditions of Soviet propaganda. It was out on Friday. But that weekend, I was out of town, on my dacha, and had no idea about it. When I arrived in the workshop on Monday, the drivers ran toward me yelling, “Damn you, old man! Why the hell didn’t you kill all the communists? Look how many of them, bastards, are still there!” “Calm down, folks,” I told them. “I killed as many of them as I could.” (Istorychna Pravda, 2013).

Raisa Andriivna—call sign ‘Ms. Raya,’ as she jokes—says that in those two decades when she was waiting for Myroslav, the government tried to recruit her cousin Vasyl who “was supposed to root around and report to KGB.” They also messed with children: “The KGB officers said they could arrange it so their son [they only had Ihor at the time] would not even know who his father was.”

In the 1990s, Raisa and Myroslav struggled. They moved to Kolomyya only in 1996. Later, Raisa moved to Verkhniy Bereziv to run the household in the house of the Symchych family that had survived intact. “I would keep up to forty turkeys,” she says. “I bought a backpack for Myroslav. He’d arrive, I’d stuff it full of food, and he’d go back. Once, we watched ten geese and ducks bathing in the brook, and he said, “Just look at it, Rayok, it’s so nice!”

We are sitting in the kitchen when Raisa gets a call from her granddaughter. “Come visit,” Raisa says. “I’ll make cutlets for you.”

The Symchych family has two sons and five grandchildren. They all are named in honor of Myroslav and Raya’s ancestors.

Raya recalls: “I have a pillowcase, earth-colored, that Myroslav brought along to the camps and put my letters inside it. He always started his letters with a greeting, “My dear sweetheart.” And he loved kissing. He smothered me with kisses. He still calls me endearingly, “Rayok.” “I love you, Rayok, as deeply as I did fifty years ago. And I will love you till the day I die.”

The UIA warrior’s relatives and friends, as well as his son Ihor, who was granted a few days’ leave from service, will come to his birthday celebration and, as usual, sing carols for him.

In 2013, Symchych said: “The Bolsheviks killed so many of our intellectuals that when Ukraine became independent, there weren’t enough people to work in all government institutions and build Ukraine we’d been fighting for.” (Istorychna Pravda) “To gain sovereignty is only part of the story—it’s much harder to maintain it. We gained it, but look how hard it is to keep it. You were given the hardest task—to keep the sovereignty.” (Ukraina Moloda).

We say goodbye to Raisa and look into Myroslav’s room on our way out. Sotnyk ‘Kryvonis’ is smiling.

§§§

[1] A military rank dating back to Cossacks. Literally, a commander of a hundred-strong unit.

[2] Groups of social brigands active in the Ukrainian regions of the Carpathian Mountains from the 16th century to the early 19th century. Opryshky were similar to the ‘noble highwaymen’ of other countries and have been idealized in Ukrainian folklore and romantic literature.

[3] A leading regular unit of the Army of the Ukrainian National Republic which operated from 1917 to 1919.

§§§

The Ukrainians Media is grateful to the Central Archive of the State Service of Ukraine, Darka Hirna, Center for Research on the Liberation Movement, and Local History for helping us prepare this material.

Collages: Grycja Erde.

Translation: Hanna Leliv.