Leonid Tyvoniuk and Marya Hvozdieva-Tyvoniuk are a married couple living in Lutsk. They share one big love—animation. IMAGO, an animation studio they established in 2015, reflects this love through storytelling, articulating senses, and talking about complex topics using simple language and fantastic imagery. Teaching children is a big part of their work. They encourage the young generation not only to master the technical aspects of animation but also to foster imagination, showcase their talents, and nurture creativity.

The duo is convinced that creative work is crucial during wartime. It makes it easier to cope with stress and tension. They advocate for starting with the simplest activities, like molding things with playdough.

The Ukrainians talked to Leonid and Marya about the realm of animation that helps people find friends, their experience working with internally displaced people, and securing financial assistance from the EU to bring creative ideas to fruition.

§§§

[This publication has been created with the assistance of the European Union]

§§§

How is it being a creative couple? Do you see it as a plus or a minus?

Marya: It might be about temperaments or our outlook on life. We approach work differently. Leonid is a workaholic who is deeply passionate about animation. I often remind him to take a break, and he counters that it’s time to make some money now that we’ve rested. So, we balance each other out. Leonid is the steady one, knowing where, how, and why he’s moving. And I’m the one stirring things up.

Initially, we had disagreements, especially about money. It all began as idea-driven volunteering. As someone concerned about the future and family, I felt uneasy. We poured much energy, time, and resources into our organization’s development without making any money. But I love my partner, believe in him, and enjoy helping him realize his dreams and ideas. At the same time, I made it a point not to lose myself in it all.

Eventually, I reminded myself to pursue my own goals and consider my projects within the organization without completely dedicating myself to my partner’s initiatives. That made a difference.

Leonid: When we collaborate on a project, it’s both a strength and a challenge. You find yourself navigating conversations with your wife and the project’s art director in one. Sometimes, you have to carefully choose words to avoid hurting either the artist in her or the wife. It’s a diplomatic skill.

How did your love for animation begin, and what captivated you about it?

Leonid: I’ve been passionate about it since childhood, creating stories for as long as I can remember. While studying at the theater department with a focus on stage direction, I explored various art forms beyond puppet theater. A friend introduced me to the works of Jan Švankmajer [a Czech filmmaker, animator, and artist,—TU]. I was blown away. The impact was so profound that I decided to venture into animation. With no equipment, I recorded my first animated video using a smartphone, and from that point on, animation became an integral part of my life.

Marya: Personally, I never delved into the process of animation.

It was akin to children not pondering where apples come from, simply perceiving them as a whole on a supermarket shelf or in a TV ad.

During my student years, I never really thought about the collaborative effort and the team behind animated videos.

I met Leonid during my senior years in art school. He mentioned his interest in animation and said he was making a video—working under the stage in the puppet theater. “You can come if you want; I’ll show you everything,” he said. So, I visited and saw that table in the darkness, with Leonid working underneath it. He showed me a puppet and explained what it was made of. And then he said he’d run out of liquid rubber to finish it. I was intrigued, thinking, “Liquid rubber? What’s that?” I hadn’t even heard of it. But I wanted to help him find it nevertheless. Around that time, my fellow students and I went to Lviv to buy art materials—the choice in Lviv was bigger and cheaper than in Lutsk, where we studied. That’s where I began searching for liquid rubber, only later realizing it was silicone.

Leonid: We soon realized that we were lacking training materials, and everything needed translation from English. I contacted my friend’s wife, an English teacher, for help translating the texts we found.

Marya: Absolutely, there was this knowledge gap. I saw Leonid struggling and wanted to help him out. That’s how I got pulled into this realm, and soon enough, I found myself genuinely interested. We began searching for people experienced in animation to learn from their expertise. The idea then emerged to organize an event, bringing together these talented people who could guide us. This led to the birth of Zadzerkallia, an animation festival, in 2016. Our goal was not only to bring experts to Lutsk to share their insights but also to raise awareness of animation among the locals.

Leonid: The festival was free because we knew people weren’t quite ready to pay for it yet, even though the information was valuable to us and others. However, we made a small mistake—during the festival, there was hardly any time to listen to the speakers we invited. We found ourselves running around, troubleshooting urgent issues like searching for a power strip while a lecture was in progress. In short, three years passed in this whirlwind. We scarcely had time to work on animation as we immersed ourselves in the festival life, studying and gaining new knowledge all the while.

IMAGO NGO was established prior to the festival back in 2015. What led you to the decision to set up this NGO, and what values underpinned it?

Leonid: One day, our friend, Olena Semeniuk, contacted us. She was organizing a festival in Lutsk as part of the Poland-Belarus-Ukraine program [Art Territory: A City of Creators, a 2015 festival of contemporary art,—TU]. She proposed that we organize the section dedicated to animation. We brought Stepan Koval and Sashko Danylenko on board, hosted a series of events, and discovered it was genuinely intriguing. Even more important was that we saw that the audience shared this interest. This prompted us to decide that this was something we wanted to pursue. We gathered with our friends and colleagues, and that’s how our NGO came into existence.

We infused three symbolic meanings into the name IMAGO. In Latin, ‘image’ means ‘a copy, likeness.’ Also, this name phonetically resembles ‘I’m a go,’ close to ‘I’m on the go,’ conveying the sense of being in motion and making progress. Lastly, imago is a stage in a butterfly’s metamorphosis. At first, an insect crawls like a caterpillar, then it turns into a chrysalis, and then this last stage arrives, when a mature butterfly spreads their wings, ready to fly.

‘I’m a go’ / ‘I’m on the go’ is a crucial rule and guiding principle for us. We do our best to make progress, keep going, and enhance our professional competencies. At first, we didn’t quite understand how to create animation. But we learned and evolved through growth, development, and numerous projects. However, we recognize that there’s always room for further growth. Progress is an ongoing journey. These values underpin our work and the activities of our organization.

Marya: When writing our NGO’s charter, we also discussed what we deemed unacceptable. One specific commitment we made was never to accept funding from alcohol or tobacco companies, as that would be misaligned with our position. We’d never impose this on others.

Funding poses a big challenge for most NGOs. What’s your strategy, and where do you seek support to bring your creative ideas to life?

Leonid: Our strategy reminds a blind moose running through a burning forest. (Laughs).

Marya: Both of us are highly creative but struggle with planning and strategizing. That’s where a team comes in—people adept at crafting compelling, well-structured grant proposals. We present the idea, and they prepare the application tailored to a specific grant.

Мар’я: Ми обидвоє дуже творчі, тож планування і стратегії нам даються складно. Для цього і потрібна команда. А саме люди, які вміють класно і структуровано написати проєкт. Ми подаємо ідею, а вони вже створюють відповідну форму й заявку, яка підходить під певний грант.

Leonid: We do some research and check which expenses can be covered by this or that grant. We’ve collaborated with a range of organizations, such as the Goethe Institute, the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation, the European Cultural Foundation, and Insha Osvita. Through these partnerships, we’ve successfully implemented projects and traveled to cities like Zaporizhzhia, Odesa, Chernivtsi, Uzhhorod, and others. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution to the issue of financing. We actively search for funding opportunities tailored to specific projects. And we’re always open to collaboration provided our potential partner shares the same values.

NGOs focuse on social missions rather than business blueprints or commerce. In our case, the financial assistance from our partners is invaluable. Otherwise, we might need to commercialize our workshops or rely on donations, which is not our usual approach.

Marya: We only charge fees for our workshops when it becomes challenging to make ends meet otherwise. We have to pay rent for our studio, and heating increases the bill in winter. Yet, we strive to have at least one ongoing project to cover these expenses and run workshops accessible to all children, irrespective of their families’ income.

Engaging with children, especially through training workshops, plays a significant role in your creative work. What drives this emphasis?

Marya: After organizing festivals for a few years, we recognized a shortage of animation experts in Lutsk. This scarcity meant there was a need for nurturing talent, and what better time to do so than in childhood? Children would grow up to become professional animators, and we almost made that happen. The kids we trained a few years ago are now between 16 and 18 years old. Those who attended Zadzerkallia are already working in studios, and many of them say, “Thank you for organizing this festival; it helped me decide on my career.”

Leonid: I enjoy working with children and sharing knowledge with those eager to learn. After all, you can only teach those who want to be taught. Working with children is especially rewarding when they’re enthusiastic about learning and willing to put in effort. The outcome isn’t as positive if a child lacks interest or simply refuses to learn.

We understand that parents may have aspirations for their child to become a great sculptor or guitarist. Still, the child might have different dreams, perhaps envisioning a career as a violinist. The same goes for animation; you can’t force someone to learn it. We can’t teach a fish to climb up lianas because a fish loves water.

What kind of impressions do kids take away from your animation workshops, and what kind of feedback do you receive from them?

Marya: The responses vary. Some kids leave the studio satisfied, saying how cool everything was. Others, like myself, who can’t sit in one place for long, get really tired. They say, “Wow, that’s cool, but it’s so difficult.” Some even declare they would never do this again. However, this realization is also important. After the workshop, they at least comprehend how complex the process is. Perhaps, when they go to the movies or watch an animated video next time, it will get them thinking about the team of people behind it and the complexity of the process. But some kids become captivated by animation, delve deeper into it, refine their skills, and ultimately make animation their career.

Did you continue working with children after the beginning of the full-scale invasion? How has the war impacted your approach to projects overall, and has it led you to focus on particular subjects?

Marya: When the all-out war broke out, each of us reacted differently. I went numb. I had no idea where to go, what to do, and what activities to undertake. I couldn’t even help myself, let alone someone else. In contrast, Leonid was focused and determined. He immediately went to the studio, saying, “I have to do at least something.” However, I couldn’t bring myself to get out of bed and cried a lot.

Later, when I slowly came back to my senses, I realized that children were the most vulnerable at that moment and needed support. Leonid and I discussed this, and he suggested running online workshops. It was a new thing for us. I’d been following a therapist based in Lutsk on social media, and her work, posts, and recommendations resonated with me. So, I suggested involving her in these workshops, as I was concerned about potentially traumatizing children with certain actions or words. Having a therapist present at such a moment seemed crucial to me. Even though I attended the first online workshop, I never turned my camera on because I cried throughout it. However, the workshop, led by Leonid, was successful. We kept those workshops relatively short and ran just a few, creating things with playdough. Still, this experience helped me pull myself together and gradually return to work.

Leonid: In the early days of the full-scale invasion, Sashko Danylenko created a group chat called ‘Graphics Battalion.’ He gathered numerous graphic designers and animators who swiftly took on various tasks: creating illustrations related to the war or responding to specific events, crafting informative illustrations, videos, or images. Initially, there was scant information, even about air raid alerts. People had to adjust, accept them as a fact, and figure out what to do when the alerts went on. The first time it happens is frightening—you’re unsure what to do. It became crucial to convey this information visually through simple and accessible means.

So, Sashko invited me to join the team working on an animated video to explain air raid sirens to children. The goal was to create an explainer to alleviate children’s anxiety. We collaborated with therapist Kateryna Pavlenko on this project. I completed it in a few days right here in the studio.

It was winter, February, and that marked the first animated video I created during the war.

But I didn’t want it to be the last one, so I suggested we keep going. Roman Dzvonkovskyi, founder of DzvonkMotion animation studio, embraced that idea. We invited a few more people from the industry, and that’s when Dmytro Shoshtak joined us. The team kept growing. Someone brought in a scriptwriter, while someone else invited a therapist. After numerous discussions, we concluded that despite the years of war, there was still a lack of basic information or explainers. Creating them for the entire Ukraine as swiftly as possible became crucial.

Who was the target audience for those explainers?

Marya: We aimed to assist various groups, including therapists, school teachers, and parents. Choosing the right words to explain complex issues can be challenging, and sometimes time is limited. These animations aimed to bridge this gap—any parent could watch them and later explain things to their child easily. Teachers at schools or nurseries could also utilize them to convey essential information: what to do during an air raid alert or how to help children calm down when it starts.

Leonid: We created five videos for this purpose, and in April, I suggested seeking funding to continue this project.

Marya: There were lots of subjects. By that time, therapists had put together a whole list of topics they wanted covered in animations. However, funding was a challenge as we needed to cover studio rent, utilities, and at least some compensation for everyone involved. While we were eager to produce more videos on this subject, we also had to sustain ourselves. Therefore, we decided to seek a grant. Eventually, Leonid and the team secured the necessary funding.

Leonid: We submitted our application to the European Cultural Foundation, and the grant we received enabled us to produce another seven animations, collaborating with five Ukrainian studios. We contributed two animated videos; Roman Dzvonkovskyi and his colleagues created two, and Ziu Poberezhniuk, Hanna Stryzh, and Valeriy Liperenko crafted another three. Dania Maliuha was responsible for creating the opening sequence.

This project is titled “Graphics Battalion for Children,” and it made sense to retain this name as it originated from Sashko Danylenko’s “Graphics Battalion.” The works are accessible for free on our YouTube channel, and people can also download them. We intentionally produced them at a low bitrate to keep the file sizes smaller. This way, parents could easily download them onto their phones while in bomb shelters. We also incorporated subtitles into the videos to ensure that people could read the content if watching videos with sound was not an option.

Marya: Certainly, watching a video alone didn’t mean healing, but it served as a small gesture of support and a helpful tip during the initial weeks of the all-out war. Everything we see, hear, read, or consume has an impact on us.

So, if someone comes across a recommendation in an animated video, reads a booklet, and then hears crucial words in a film, the cumulative effect can be significant.

This may prompt this person to respond to their internal needs, seek therapy, engage in self-care, and potentially avoid causing trauma to themselves or their child.

So, in essence, mental health and support have taken on significant importance for you since the full-scale invasion began. Specifically, you’ve been involved in efforts to assist internally displaced people in adapting. Could you provide more details about your project ‘Animation Unites,’ which you implemented with the support of the European Union? What was the goal of this initiative?

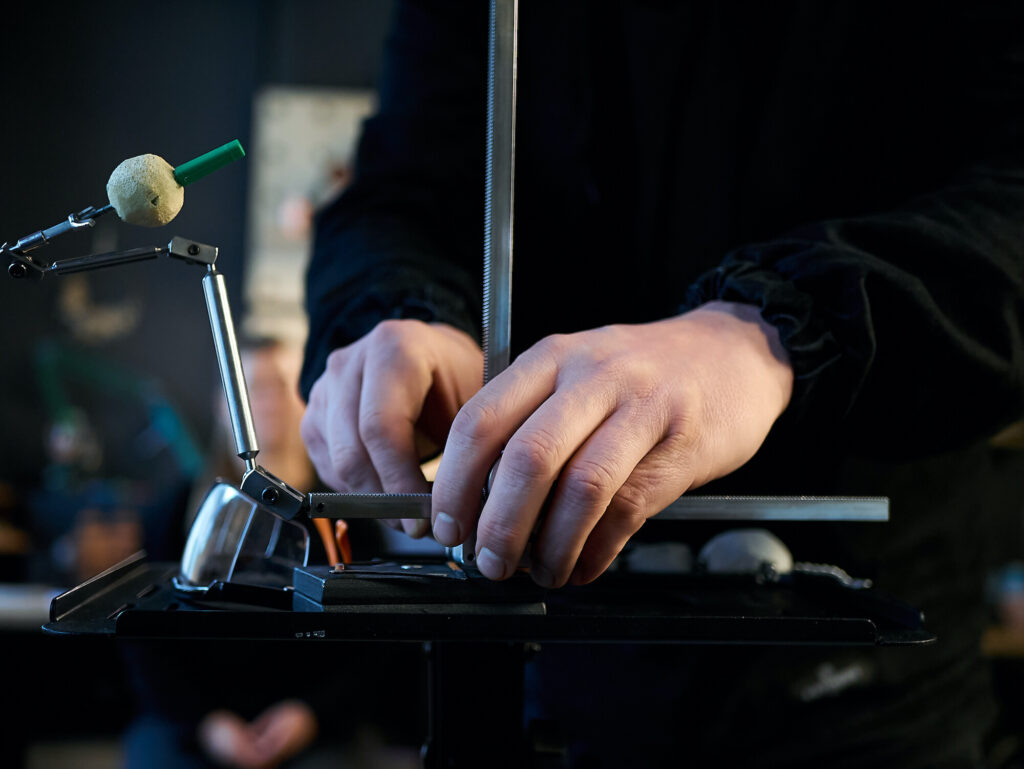

Leonid: Many children from other Ukrainian cities moved to Lutsk during the full-scale invasion. Numerous families were forced to leave their homes and find refuge elsewhere, and many settled in Lutsk. So, we initiated this project to facilitate their integration and help them become part of the city’s life. One of the conditions of this grant [provided by the project “Culture Helps / Культура допомагає,” co-funded by the EU and implemented by Insha Osvita (Ukraine) and zusa (Germany)—TU] was involving a specific number of Lutsk residents and teenagers who had been displaced from their homes. Our concept was to engage them in the creation of animation.

We believe that animation has a unique way of uniting people. It’s all about collaboration, creativity, and the opportunity to open up and let your imagination thrive.

Animation has the power to help people reveal their talents. When the project started, none of the participants knew each other. However, by the end of it, many had formed genuine friendships. We’re so happy to see them now strolling together in town. The fact that complete strangers could find a common language and become friends is truly awesome, and it’s great to know you’ve played a part in that. Animation has indeed united people.

We invited 20 children to take part in this project. Initially, there was a selection process. Children wrote motivation letters and submitted their works, highlighting their talents—some loved drawing, while others were passionate about dancing. We received around 90 applications and chose 20 participants, dividing them into two groups of ten kids each.

Group one focused on creating animations using playdough, while group two worked with felt—an entirely new experience for our workshops, as we hadn’t worked with felt before. Last year, I created an animated video titled “Mum’s Mission,” based on a guidebook prepared by therapist Lesia Kovalchuk. This guide outlined an action plan for mothers leaving the city with their children, explaining how to behave and stay calm to avoid traumatizing the child. For this project, I chose to work with felt. I found the material appealing and thought it would be a great fit for this workshop, too. Originally, we aimed to produce a series of videos but eventually intertwined several ideas into one cohesive plot. As a result, we produced a sort of mini-series.

We’re thinking about continuing this project. So far, we’ve completed two episodes. In each episode, the protagonists must solve a puzzle to get the key to open the door and climb to the next floor. Our concept envisions a series of nine videos where children explore different materials like paper, pixilation, and puppet animation. The story goes like this: a group of kids go on a tour of a castle dungeon and find themselves in a magical world. Their challenge is to return to the human world by overcoming various trials. In the first episode, they transform into playdough characters, and in the second, into characters made of felt. By the end of the journey, they must get as close as possible to the human image—become humans again.

How did that project finish? What was its value for you?

Marya: This project was valuable for both the children and their parents. We didn’t task the kids with finding friends along the way—it wasn’t an explicit goal. However, as they collaborated in the studio, interacting daily, they naturally discovered shared interests.

As we neared the end of the project, we had plans to organize a celebratory picnic for everyone involved. A few mothers shared that arranging outings with their teenage children wasn’t always easy. This made sense, considering that as kids grow up, they often prefer spending time with their friends. After showcasing the works and presenting certificates, we enjoyed pizza, organized some fun competitions, and simply hung out together. One mother said that it was the first time since the invasion began that she felt great and comfortable, finally able to relax a bit. People truly valued the opportunity to come together. It became a small celebration that left warm and cherished memories.

Leonid: And, of course, we got to teach children to create animated videos. This is our objective for every project. While our overarching goal is to make as many people as possible fall in love with animation, teaching animation is not our top priority. Our foremost aim is to inspire kids to imagine and create, helping them discover their talents.

Is working with internally displaced people different in any way compared to what you usually do?

Marya: Working with internally displaced people didn’t feel that different for us. They were just kids. During the initial session, they introduced themselves, sharing their names and hometowns. Hearing someone say, “I’m from Mariupol” or “I’m from Mykolayiv,” you couldn’t help but think about what was happening in those cities. Some teenagers from Lutsk even oohed and aahed when they heard the names of those cities. However, in essence, they were just kids.

There was this girl from Kherson. She often said how much she enjoyed living in Lutsk. But she also said she wanted to return home because her grandparents still lived there, and her family planned to visit them in the summer. “Are you serious?” I asked her. “Aren’t you scared?” To which she said, “Why should I be scared? I’m no longer scared of anything. And then, my loved ones live there.”

In September, we all gathered for that celebratory picnic. When I saw her, I recalled our conversation and asked her if they managed to go to Kherson. She said they did; it was great, and she was happy. I found it wonderful that she visited and equally wonderful that she returned to Lutsk, where they had already established a life for themselves. This girl has a talent for drawing. For a while, her parents hesitated to send her to the local art school. I presume they were reluctant to settle down permanently and waited until they could return home. However, at the picnic, they asked me about an art school or studio she could attend. It seems they had come to terms with the unfortunate reality that returning home wouldn’t happen as soon as they had hoped.

However, working with children in cities close to the frontline is a somewhat different experience. For another project, we visited Mykolayiv, Odesa, Dnipro, and Zaporizhzhia, and the kids in those cities were clearly distinct from the kids in Lutsk due to their different day-to-day reality. Our approach with these kids followed a familiar pattern: greetings, introductions, and working with playdough. Essentially, we just ran our typical workshops. However, the conversations surrounding them were different—kids talked about missiles and explosions. Children in those cities no longer seemed scared; they even laughed it all off. This created a contrast: when the air raid siren went off, I, an adult, felt scared and asked them to head to the bomb shelter. Yet, the kids simply waved me off, saying there was no point.

In workshops like this, creativity is not a top priority; it’s much more crucial just to be together with children. Sometimes, all you need to do is listen to them, offer a comforting hug.

Another thing I remember from my conversations with kids in places like Zaporizhzhia is that they still haven’t returned to school—they’ve been engaged in online learning all this time. They all complain about it and say they’re sick and tired of it. They find it boring and difficult. After all, nothing is better than live communication. This is clearly what they miss the most.

Despite these challenges, people in these cities are adapting to the situation. As an example, a teacher took the initiative to bring her students to one of our workshops. She discovered information about our project and organized the visit for the kids as an extracurricular activity, giving them a chance to spend time with their classmates. I believe this generation of children will have a newfound love for attending school. They already appreciate any opportunity to get together.

Why are creative activities so important for children who have had stressful experiences? How can they help?

Leonid: I believe that creative activities are important for both children and adults, serving as a form of therapy. However, you must be aware that art can heal or hurt just like any medicine. It all depends on the regularity and dosage.

Creative activities can take various forms. It depends on what someone needs most at a given moment. Sometimes, expressing aggression through creative activities helps release negative emotions. During one of our workshops in the early weeks of the full-scale invasion, a child vigorously pounded playdough, channeling their pent-up rage and fatigue. This was clearly what the child needed—not looking at or creating beautiful things.

The act of creation allows us to unite our bodies and emotions in here and now, capturing that concentrated moment in, let’s say, a piece of playdough. This tactile experience lets the child shift focus and connect more deeply with their emotions.

Does creative work have a therapeutic effect for artists, too?

Marya: I know that the impact of war on many artists, in terms of their creative work, has been overwhelmingly negative. The war has blocked their emotions, which are the driving force behind their creativity. This is particularly detrimental for artists, for whom creativity is not just a passion but also a means of livelihood. What’s more, creative expression serves as a way for people to process their traumatic experiences. Pent-up negative emotions can lead to problems if there’s no outlet. And you have to turn to therapy to process that.

We have a group chat with other animation artists. And many members of this group have said they were either depressed or close to it. Quite a few find themselves unable to create. Many people abandoned their creative careers altogether and found other jobs to make a living or just afford basic things like buying medicine or paying for therapy sessions. For others, the war became a push. Some people reinvented themselves in a different genre. For example, they took up illustration and began making postcards and posters about the war to raise awareness among the wider, global audience.

There was a period when I just couldn’t go back to drawing. Then I decided to return to the works I started before the full-scale invasion. Yet, I just could not do it. There was this kind of block. I couldn’t do it no matter how hard I tried. Then, I reached out to a friend. She also works in this industry, curating exhibits. “Katia,” I said. “I have to finish these works.”

And she looked at them and said, “No, you don’t have to finish them. Draw what you’re feeling now. Draw what you’re going through, anything happening in your life or the country. Live through what’s there now. You’re just trying to get back to your previous life. But it will never come back.” Then, I realized I had to move on and work on new projects.

So, for different people, art serves different purposes. But I reckon it’s not just creatives who need art. Even those dealing with numbers or paperwork or people serving in the military—their brains get fried, and they need a break, a shift from their usual grind. War is all about destruction, and art gives them a way to shift gears toward creation.

The publication was prepared with the support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the position of the European Union. NGO “IMAGO” received support for the “Animation unites” initiative within the “Culture Helps” project, which is co-financed by the European Union within the framework of a special call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced persons and the Ukrainian cultural and creative sectors. The project is implemented by Other Education (UA) and zusa (DE).