The Babylonʼ13 group, a Ukrainian collective of documentary filmmakers, was originally founded to document the Revolution of Dignity. Today, its members document Russia’s war against Ukraine. Volodymyr Tykhyi, filmmaker and producer of Babylonʼ13, is working on one of these films: With financial support from the EU, he is recording the history of Russian war crimes against the healthcare infrastructure in the south of Ukraine.

We spoke to Volodymyr Tykhyi about the role of documentaries during the war, the artistic interpretation of Russian crimes, and the future of non-fiction films.

§§§

[This publication has been created with the assistance of the European Union]

§§§

In 2013, a group of Ukrainian film directors and cameramen came together and founded the Babylonʼ13 collective to record decisive actions by civil society. The first recording was Prolog, a short video shot on Mykhailivska Square in Kyiv on November 30, 2013. Do you remember how you started?

This story is impossible to forget. We didn’t just came together—it was an explosion of self-determination. Everyone was outraged by the beatings of the students who took to the streets to protest. Denys Vorontsov, our activist from the Babylon’13 group, suggested that we meet in Mykhailivska Square and start filming.

It became clear that, as filmmakers, we could directly influence the process. At that time, almost all the media were under the influence of the government, so we had to show what was really happening in Ukraine.

We weren’t thinking so much about the Ukrainians but about the foreign audience—our goal was to show them what was going on here and to use the documentary genre to make sense of reality. That’s what we joined forces for.

A few weeks later, we realized that the people on Maidan were interested in what we were doing: It was important for them to see themselves not through the news but through certain artistic images. Babylon’13 set a cultural process in motion. We became a kind of Maidan media or cultural platform.

What goal did you pursue then?

Our goal coincided with the goal of Maidan—the change of power and the toppling of the Yanukovych regime. Although our team included experienced film directors and cameramen, experts with certain backgrounds and successes, we decided to make the videos anonymously. This is how Babylon’13 emerged as an art brand. The concept was this: Several people make a movie without claiming authorship. This principle still applies today. The films published on Babylon’13 social media—on YouTube or Facebook—are anonymous. They are inspired by social responsibility and the realization of how important the things we talk about are. We don’t try to promote ourselves or make a career out of them.

So, could we say that you have joined forces to highlight and reinforce

the changes in society?

We got together to tell people what was happening here, in Ukraine, on Maidan. Back then, hardly anyone reported on it. We produced documentary reports and published them. Media all over Europe, the United States, and Russia quoted us. At first, we thought we were working for an audience outside Ukraine, but then we saw how important it was for Ukrainians themselves to see what was going on in Ukraine.

By the way, why Babylon?

After the meeting with Serhiy Trymbach, the head of the National Filmmakers Union of Ukraine, we were provided with a small workroom where we could project videos. The room was located next to the Babylon Bar, which was named in honor of Ivan Mykolaichuk’s film of the same name (Babylon XX, a 1979 drama—TU). The password for the Wi-Fi we used was Babylon-13, where 13 stood for the year 2013. So we decided to call our association exactly that.

Our name emphasizes the continuity of cultural processes—from Mykolaichuk to the Revolution of Dignity.

It is also symbolic that Babylon was a place where many people were searching for a common language, just as they did in Ukraine in 2013.

Babylon’13 has continuously chronicled historical events for almost a decade: from 2013-2014 (the series The Winter That Changed Us; the film Our Hope) to the full-scale invasion (the series Mariupol Fortress about the city’s defenders; the stories about Ukrainian soldiers Kestrel. Field Stories; the documentary series about the artists Art in the Land of War). What’s your perspective on the path you covered for the last decade?

We create short artistic stories rather than chronicles. Even if they are documentaries, they are artistic interpretations and have certain images and ideas.

A documentary differs from a reportage not by the amount of material or length but by the artistic background of its makers. Through the visual narrative, a documentary filmmaker communicates their thoughts and their personal view of the world. If a filmmaker tries to manipulate or imitate something, their work quickly loses its value or doesn’t get out at all. It also doesn’t justify the investment involved: time, money, and so on.

Experienced filmmakers with international festivals and all kinds of success behind them have skillfully taken our work across borders. The short video stories were perceived without translation as independent messages, as an emotional experience. People abroad who did not understand how the events on Maidan unfolded watched them to inform themselves.

The movie Our Hope is a post-story, while our documentaries show the here and now. Let’s say the day before people came to Hrushevskoho and Instytutska Street, the first Molotov cocktails exploded—and we immediately shot and released a series of videos about it. With the energy boost we got during the revolution, we created the series The Winter That Changed Us. I contacted Natalka Yakymovych, the producer of the TV channel 1+1, and suggested a collaboration. It was a miracle that Oleksandr Tkachenko (the then CEO of the 1+1 Media Group—TU) gave the green light. In our videos, we showed clear social manifestations of the revolution. A month after the victory of Maidan, this

project went on air. It was an effective collaboration involving many film directors and cameramen.

What is Babylon’13 like today? What has changed since it was founded?

The war in the east of Ukraine was slowly eclipsed by other issues, and the Anti-Terrorist Operation turned into the Joint Forces Operation, but we kept talking about it. We knew that Russia would continue to strangle Ukraine. For a while, we were (and still are) witnesses to the war. Now, everyone is talking about this war. It has eclipsed everything else. Society is not trying to grasp reality but to survive.

Since then, a new generation of creators has emerged. These are students from the Maidan era, new blood. They attract new investments, especially grants, which Ukrainian artists were quite skeptical about. We have received funding from the International Renaissance Foundation and Western partners. Our team makes films not only for our own YouTube channel but also on demand. We made the series Position Ukraine for the Suspilne Broadcasting. Some films are created for screening, such as the feature-length films The Day of the Ukrainian Volunteer Fighter or The Independence Day. The first was screened at festivals and bought by the BBC. The second was shown in Ukrainian cinemas on the eve of Independence Day. The film processes have thus reached the level of industrial stability.

Who are the members of the Babylon’13 collective? What are your filmmakers working on right now?

Our team consists of dozens of people. There is the young filmmaker Roman Liubyi, who has made two feature-length films for Babylon’13. The first film was released a few years ago, before the invasion. It is entitled War Note and was compiled from the private videos of volunteer fighters who joined the ATO in 2014-2015.

The other film Roman made, Iron Butterflies, is now being screened in cinemas. It is about the shooting down of the MH-17 passenger plane—another Russian war crime. Roman is now working on a feature-length animated film about epic creatures, the story of which is based on Ukrainian folk tales and legends. Test filming, financed by Western partners, is underway.

Roman and I are also working on a project for the 10th anniversary of Maidan. It will be a feature-length documentary called The Maidan Time Machine. We will take our audience back in time to the heart of the Revolution of Dignity. We shot a lot of footage back then that was just waiting to be used. The art form will be quite bold, even though we will stay within the boundaries of documentary film.

Film director Yulia Hontaruk, who made popular short films during Maidan, is now working on the project Company of Steel about the warriors of the Azov regiment. Yulia filmed them on Maidan and has been editing the footage ever since—this process can take years. At the same time, she is working on short films that function as independent works of art. Yulia was in contact with the fighters of the Azov regiment and shot the series Mariupol Fortress about the Ukrainian military during the encirclement. Dmytro “Orest” Kozatskyi, the former head of the Azov regiment’s press service, was her eye and her

cameraman on location.

Another young filmmaker, Kostiantyn Kliatskin, managed to shoot a 25-part series about Ukrainian artists, Art in the Land of War, which was published on our YouTube channel. He brought so many movie directors together! That’s a Babylon’13 effect—when film directors join forces to process real stories.

Other filmmakers, such as the cameraman Yaroslav Pilunskyi or the film editor Ivan Bannikov, have gone to the war. They are our very own “Babylonians” who were involved in the production of The Independence Day and retain their place in our pool of experts. Cameraman Yuriy Pupyrin, who is now on the front line, is shooting a film about the artist Volodymyr Bezrukyi, a Muslim who is fighting for Ukraine in the Sheikh Mansur Chechen Peacekeeping Battalion.

This is a kind of cameo panorama of Ukrainian filmmaking.

To what extent is the format of a creative collective beneficial for each individual member—and for Ukrainian filmmaking as a whole?

Before 2013, I stumbled upon the term “creative collective” while watching Soviet movies. When we chose this kind of definition, we were not quite clear what it was. We have formed a community of artists—“Babylonians”, as we call ourselves—and as this community, we make feature films and documentary projects. It’s a kind of club where we work together on creative concepts and visions or support each other financially when necessary. Sometimes, you have an idea, arrange things with your fellow cameraman, and the two of you just go and shoot. If we don’t have enough money, we just make do with the resources and capacities we have. In this way, there is a permanent creative project whose principles were already shaped during Maidan.

We create large documentary film projects. The First Company, a project by Yaroslav Pilunskyi, Yulia Sashkova, and Yuriy Gruzinov, is already a cult film about our heroes, the first hundred of volunteers on Maidan, who later united to form the Kyivan Rus volunteer battalion. The film attempts to make sense of the historical event and also recreates a series of archetypes on the level of artistic images.

We at Babylon’13 have set in motion an active artistic process that works nationwide. Young filmmakers are growing up, sharpening their tools in documentary shorts, and in a few years, they will be able to make remarkable feature films.

Ukrainian society needs a high-quality cultural context.

Some filmmakers still rely on the school of social realism, while others try to imitate the formats that are popular around the world, like Netflix or other Western platforms. But we need our own cultural environment that revolves around urgent issues.

At Babylon’13, we unconsciously process reality and create materials that will later bear fruit. Maybe Antonio Lukić, who is not a “Babylonian,” will make a great dramedy about Ukrainian art based on our 25-part series about artists in wartime.

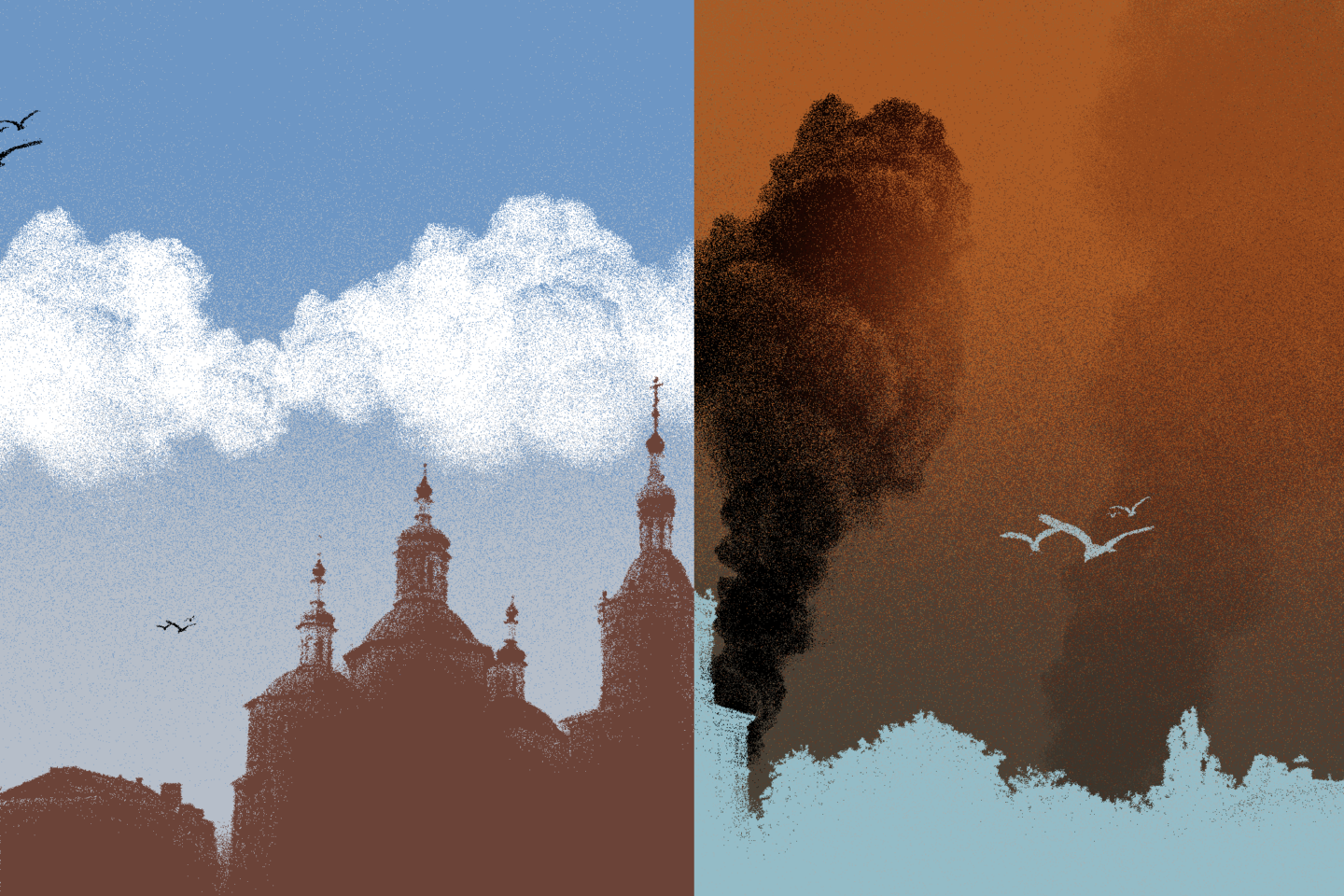

You are working on documentaries about Russia’s war crimes against the healthcare infrastructure in the south of Ukraine. Tell us more about these films.

There are two of them. The first is about the episode that happened almost a year ago. It is a story about the multidisciplinary hospital in Bashtanka (Mykolaiv region), which can accommodate up to 200 thousand patients. There is a larger hospital only in the regional center, in Mykolaiv. We tell how it survived and continued its work after the Russian missile attacks.

And Kostia Kliatskin is working on another film that shows the current operation of healthcare facilities in a small town in the gray zone where military operations take place

What is the goal of this project?

The Russians have destroyed more than 200 healthcare facilities in Ukraine during the war and damaged many others. Over time, we will feel the irrevocable consequences of these actions when some people will simply not be able to get the medical help they need. This will affect the quality of life and the mortality rate among Ukrainians. It is not enough to raise awareness of this problem in the media only—it has to be raised through all possible means. We do this through documentaries.

The Russians are well aware of their crimes against the healthcare infrastructure: they know only too well that they weaken our troops when they kill doctors and destroy hospitals.

The war waged within the limits of humanitarian law is an illusion. The dilemma of whether it is a crime or not does not even exist for Russians

In our films, we seek answers to the following questions: how to live during the war and what to do next; what social scenarios our doctors and other healthcare professionals have chosen; and how they have persevered.

It is worth noting that the health system was reformed before the full-scale invasion—and it was this reform that enabled the system to respond to the war in a very different way. At one point, we worked with a team of reformers led by former Health Minister Uliana Suprun and realized that most health professionals had a negative attitude toward reform. But in the end, this reform became a lifesaver. I think that these films will inspire us to tell more stories. After the release, we will analyze if the audience is interested and if there is an impact, and then we will continue working.

How do you shoot these films?

Fortunately, the case of Bashtanka Hospital is quite well known: The media have reported on it, and the municipality has received some funds and started to repair the damage. But there are other problems. People residing in more remote areas, far from the regional centers, tend to be less welcoming to film shoots. The state institutions there are not open to contact and mostly stick to Soviet assumptions. People are not prepared to step out of the roles they have learned or to adapt, so there is a lot of prejudice against filmmakers.

At the front, things are different: due to the shock and adrenaline rush, people there are open and proactive, while a few kilometers away from the front, people are mostly reserved, keep their distance, fall back on familiar scenarios, and are no longer sincere. For a documentary filmmaker, this is a disaster.

When we arrived at the Bashtanka hospital, we were given a ready-made story —we recorded what people had already told others many times. We were supposed to find the doctors who did their work efficiently and tried to be as unobtrusive in the frame as possible.

Kostia had a different story because he was looking for new, noteworthy things where damage had just been done, and people weren’t willing to cooperate at all. They had tons of problems and didn’t need people with cameras on top of it all. So we had to handle everything through official permits and other bureaucratic paperwork and contacted the spokesperson of the operational command “South,” Natalia Humeniuk. We continue to fight against the Soviet legacy approach to communication and self-presentation. Public figures live within the confines of primitive scenarios that they themselves have created and that restrict creative freedom and self-reflection. The protagonists lack flexibility and mobility.

How should one work with people when making documentaries during the war?

The documentary is a moment of trust during or after an incident. When someone finds themselves in a life-threatening situation, they open up, and the camera immediately sees them with different eyes. The real challenge for the director is to stick to the concept and the task they had at the beginning. There are often fewer heroes in the story than people who want to show that story.

I remember what it was like on Maidan: one person threw a Molotov cocktail, and five people stood around them with cameras. Later, there were memes about it. That said, this didn’t necessarily mean that these videos became a real story about a person with an explosive.

Often, such an emotionally charged work never came to a conclusion: the author lost the energy and inspiration they had initially, and the project remained unfinished.

Who is your target audience?

Our target group is hundreds of thousands of healthcare professionals in Ukraine. I hope that when they see their colleagues from the outside, they will be able to process their own war traumas and feel like conscientious citizens working in the healthcare sector. These films can certainly be shown at medical conferences. We are working with a non-governmental organization that is documenting Russian war crimes against healthcare infrastructure in Ukraine. They are collecting evidence for the international trial, especially in the Hague, to ensure that Russian crimes are punished.

But works of art, including documentary films, cannot be used as evidence in court.

Correct. Our films are not evidence but a visualization of the damage, showing the situation and the aftermath of Russian crimes. And ultimately, they can help ensure that Russians compensate for the damage they have done.

Already during Maidan, I was confronted with the fact that our films are not evidence. The investigators accepted our videos but could not use them as documents because they required a completely different format: you had to state the name of the person giving evidence, the date and time, and record it without interruption, otherwise, it shall not be considered an official statement.

However, our documentaries work on a different level. They serve as a foundation that emotionally reinforces the evidence. The number of the missile, its trajectory, the damaged building—all the things presented in court are dry facts, while the essence of the crime lies beyond them. It lies in the testimony of the people who suffered, in the reactions of the people.

What challenges did you face while working on this project?

I had expected that we would have more visual material about the work of doctors. But unfortunately, people living in small towns are still not taking advantage of digital technologies. They don’t record videos—an imaginary self-narrative consisting of a static image in the form of a selfie takes over. There is no self-documentation that would help to expand the space around them.

When it comes to medical crimes, there’s another problem: a large number of stories are outside the public sphere, which means we may not even know about them.

And that means that a certain number of Russian criminals will not be punished. So, we need to improve media literacy in Ukraine.

In 2013, you came together with the idea that it is possible to change people’s perception of reality and the state of things through documentaries. What role does this genre play today?

It is the only appropriate form that lets you talk about the ongoing war. This genre allows you to work completely independently, even when resources are limited. Making feature films today is impossible. I’m afraid that the films that are coming out won’t do justice to the subject of war, and people will resort to another sweeping generalization that says we’re bad at making films about ourselves and that we should let Hollywood do it.

Documentaries work with the harsh reality. Ukrainians today have limited opportunities to watch movies and deal with contemporary cultural context—we use our internal resources and time to survive. At the same time, many people, including filmmakers, find themselves in this cultural melting pot in which documentary film plays a key role.

How can we avoid entering the field of propaganda if we want to change people’s perception of reality?

Propaganda is an oversimplified perception of the world. Even if it refers to some kind of document, it always makes a claim to social perfection. Propaganda intimidates and points to the supposedly only correct way of behaving or the only correct state of things. And it often has a completely different effect than intended. For example, it claims: If you masturbate, you will burn in hell. People do this out of defiance, realize that the punishment is not coming, and continue to dismiss this assertion.

Making propaganda in a work of art is a question of morality and the social responsibility of the artist in question.

The “Babylonians” have their own cultural background that does not allow them to make propaganda. Moreover, propaganda is manipulative because it lacks artistic freedom, and without it, a documentary film is not possible.

War films are often emotionally charged and dramatic. How can we avoid this?

Right now (in September 2023—TU), The Independence Day, a movie we shot in 2022, is playing in theaters. There were five heroes, seven locations, and nine camera crews. The people in the frame are just going about their lives, but the movie is a complete art form. There is a war in Ukraine; we are all trying to survive, and the audience wonders how we managed to make such an uplifting movie about the lives of Ukrainians and their destinies. One day, it can be made into a feature film. In a way, we are documenting the experiences of different people during the war to return to them later.

How did the optics of Ukrainian documentary filmmakers change after the beginning of the all-out war?

Filmmakers are human beings like everyone else and experience this war in the

same way. And war destroys everything and brings nothing. It seems to free you

from prejudices and dependencies and forces you to make quick decisions, but

in reality, things are much more complicated.

Some people hide from death, violence, and humanitarian disasters. Others try to do something about it: They join the army as volunteers without any previous experience. At best, they make a few videos about the war. But when they are confronted with the horrors of war on the front line, they become as sensitive to trauma as children.

On the other hand, despite the war, some of my colleagues have managed to overcome their inner barriers and get their creative processes going again. They feel that Ukrainians need their creative work, as was the case during the Revolution of Dignity. Making a movie takes time and the continuity of certain processes, and many find that helpful.

The making of documentaries has taken on a very pragmatic dimension. One film editor I know, for example, has received call-up papers and has been drafted as a video director for secret military operations, where he will use his professional skills.

The protagonists of contemporary documentaries about Ukraine—who are they?

These are the military and people of all kinds of professions and jobs related to war, including volunteers. War is the most dramatic event in Ukrainian life today. Without a cultural understanding of this issue, we will not move forward. The main heroes of the process are the military, their spouses and relatives.

I am glad that we have no outside mentors to teach us how to talk about the war. Yevhen Hlibovytskyi, a member of the Supervisory Board of Suspilne Broadcasting, often talks about how foreign experts flocked to Ukraine after the Revolution of Dignity to teach us how to build democracy. But their methods were irrelevant to Ukrainians. Fortunately, no one is telling us yet how to build a society during the war.

How is documentary filmmaking evolving? Is it possible to draw a clear-cut line between it and fiction films?

Today, techniques often move from one genre to another. We want to use documentary films to raise awareness of what is happening in Ukraine. There is no time for experiments because experiments are always risky, and we cannot afford to risk our resources. Even when we experiment, we do so out of desperation rather than artistic curiosity.

I can talk about the European context here—French films or Italian neorealism, which were actually semi-documentaries aimed at an eager audience, cheap to produce, and matching social demand. The Ukrainian audience is not in the mood for documentaries because the desire to escape the traumatizing, complex reality prevails, so those examples from Europe won’t work.

Film and art critics warn that the development of feature films could come to a standstill due to a lack of funding. What do you think about the future of non-fiction films?

Non-fiction cinema cannot exist separately from other cultural areas. It interacts with feature films, literature, art, and so on. It will exist even under such difficult conditions without financing or distribution platforms. I think that filmmakers working with long form will look for a language that is appealing and understandable to Western audiences. Short form will be used to play up to the audience, as we can already see with popular bloggers.

We at Babylon’13 stand firmly on our feet and will stick to our rules. But I’m not sure if this will become a trend. Our work successfully achieves its objectives through interactions with specific social groups.

This publication has been created with the assistance of the European Union. The authors are solely responsible for its content, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent those of the European Union. NGO “Babylon’13 Creative Collective” received funding “to create documentary films on the history of Russian war crimes against the healthcare infrastructure in the south of Ukraine” as part of the European Renaissance of Ukraine project implemented by the International Renaissance Foundation with financial support of the EU.